Programme 8-9 am: Registration 9 – 10.30 am: Inaugural Session Chair and Welcome address: Dr.…

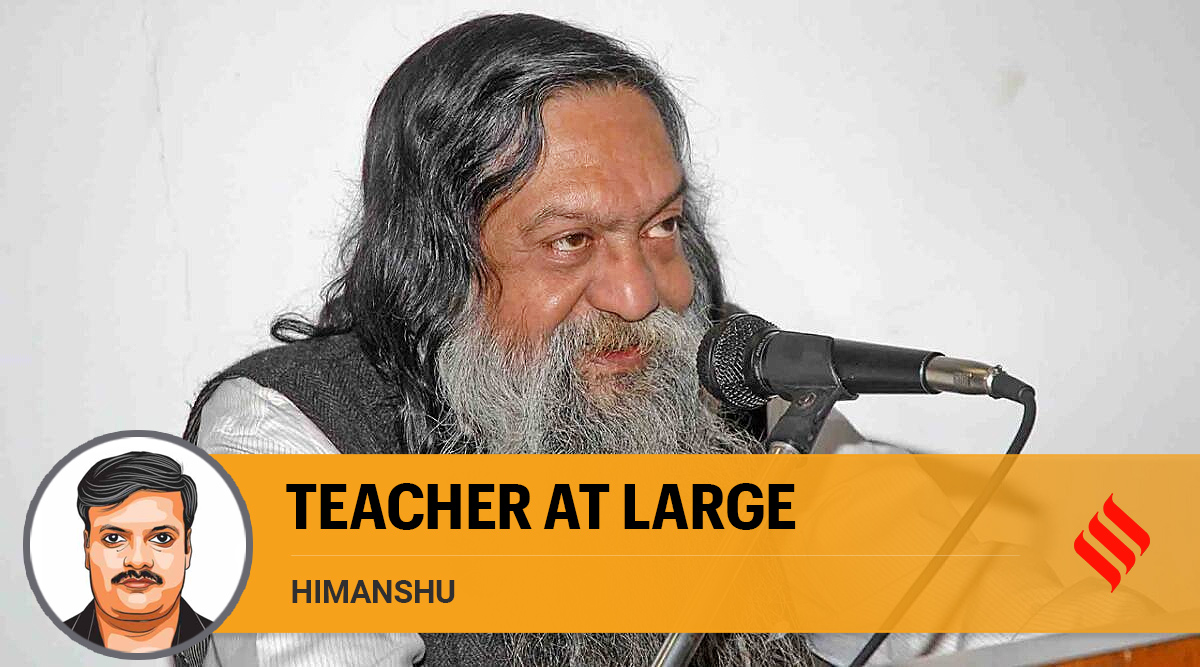

Economist Abhijit Sen believed in Power of Policy to Achieve Growth, and Alleviate Poverty Himanshu

Professor Abhijit Sen, economist and former faculty at the Centre for Economic Studies and Planning (CESP) in Jawaharlal Nehru University passed away on August 29 due to a sudden heart attack. Primarily a teacher, he was also involved in policy-making in various roles for more than a decade — as a member of the Planning Commission (2004-14), the 14th finance commission and chairperson of the Commission for Agricultural Costs and Price (CACP), among several other positions that he held during his almost two decades of involvement with policy making. But even during his leave of absence to advise the government on policy issues, he continued teaching and supervising research scholars at CESP throughout the three decades that he was associated with the centre. He remained a quintessential teacher-at-large for several students at JNU and elsewhere, bureaucrats, journalists, activists and anyone else who was willing to learn. It was not unusual for him to pick up a marker/chalk and start teaching in formal meetings or during informal get-togethers.

Sen was primarily an agricultural economist, starting from his seminal PhD thesis submitted at Cambridge University on the ‘Agrarian Constraint to Economic Development’. His basic proposition that agricultural problems remain the primary constraint to growth, based on a careful analysis of the post-Independence economic growth of the first three decades, remains relevant even today. His thesis argued that the root of the agrarian problem lies in the structure of Indian agriculture and increasing input intensity or institutional mechanisms such as share-cropping are unlikely to take care of the problems of surplus labour and poverty in agriculture. The nature of the agriculture problem is unlikely to be resolved without state intervention given the existing agrarian structure. For Sen, the resolution of the agrarian problem was not just key to overall growth but also necessary to take care of the problem of mass poverty.

Sen’s understanding of Indian agricultural problems based on his subsequent work on agriculture only confirmed his belief in the necessity of state intervention, something that he tried during his stint at the CACP and later through the High-Level Committee on Long Term Grain Policy, 2001. He argued for remunerative prices to farmers along with universalising the Public Distribution System (PDS), a belief he held and argued for during the debate on the National Food Security Act (2013). As a member of the Planning Commission, he argued for expanding the coverage of the PDS under the NFSA to make it near-universal, if not fully universal.

For him, the role of public policy was not just to achieve growth but also improve the lives of the poor. This belief came not just from his analysis of poverty trends in India, a subject that he deeply engaged with, but also from his profound engagement with policy and the role of the state. Sen’s contributions to the measurement of poverty and underlying data on consumption expenditure are recognised in India as well as globally. In particular, his contribution to the first ‘Great Indian Poverty Debate’ on some of the methodological issues not only forced the government to abandon the controversial estimates of poverty for 1999-2000 but also helped in further refinement of the methodology of data collection on consumption expenditure. He also contributed to the Tendulkar Committee report on poverty lines.

Sen’s firmness on various issues in policy circles and academic debates was perceived differently from different ideological perspectives. But his belief and firmness also came from his ideological commitment to facts based on hard data. It was this belief in dispassionately engaging with data that earned him praise and respect from various ideological quarters, despite divergences in approach. He also did not have biases about the sources of data. For him, facts came in different forms. Despite his ease with large-scale data, he was equally comfortable with and willing to engage with primary data coming from village surveys or through his interaction with activists. He was willing to let go of his own beliefs and ideas if the facts contradicted them and revise his opinion. It was this humility that endeared Sen to students as well as fellow policymakers and bureaucrats. His openness also helped him appreciate students, academics and activists from other disciplines.

The hunger to learn also meant that Sen published much less than he could have. It was not laziness but his quest for the complete story and understanding of all aspects of an issue which made him a less prolific writer than many of his contemporaries. He never wrote a book and published little but he would always encourage young researchers to publish and guided them with whatever knowledge, data and information he had. He had many more unfinished and unpublished papers than the ones he published. His desktop never shut down — even when he was unwell during the last two years, he continued working on his Excel files. He had much more to contribute, especially during the current period when his wisdom and knowledge are needed to make sense of what is happening to poverty, inequality, employment, state finance and many other issues on which he remained the authoritative voice for many.

(The writer is Associate Professor, Centre for Economic Studies and Planning, Jawaharlal Nehru University.)

(This article was originally published in The Indian Express on August 31, 2022)