The Marxist sociologist wrote incisively about the way in which capital-labour relations played out in…

Thandika Mkandawire Laura Mann

Thandika was above all a really kind soul, generous with his time and patient with younger scholars who were still trying to make sense of the world. Although he had personally lived through all the twists and turns of African economic history and development thinking from the 50s onwards, I always got the sense that Thandika wanted younger people to make up their own minds on their own terms.

He was committed to the nuanced and complicated truth. Never one to self promote, he wrote concisely and clearly, ruthlessly dismembering lazy ideas and setting the world right with a great deal of grace. Although he was critical of the idea of a ‘marketplace of ideas,’ his own ideas did speak for themselves. Everything he wrote is a favourite of mine. And sometimes I wish he was more of a self-promoter so that the intellectual marketplace could be a little more nuanced!

I consider teaching alongside Thandika to be one of the greatest gifts that life has given me. He has fundamentally changed how I think about development. Here are some of the things I learned from him:

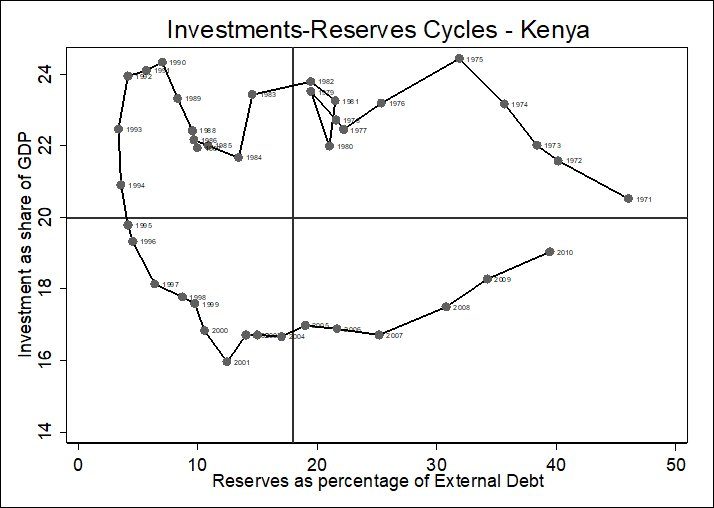

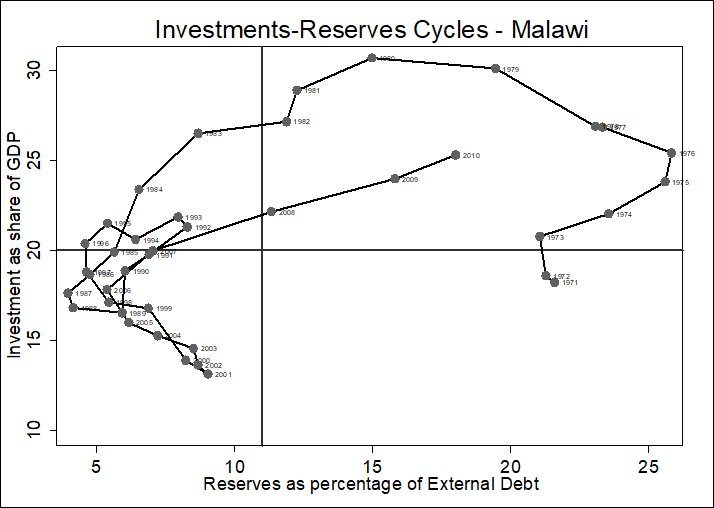

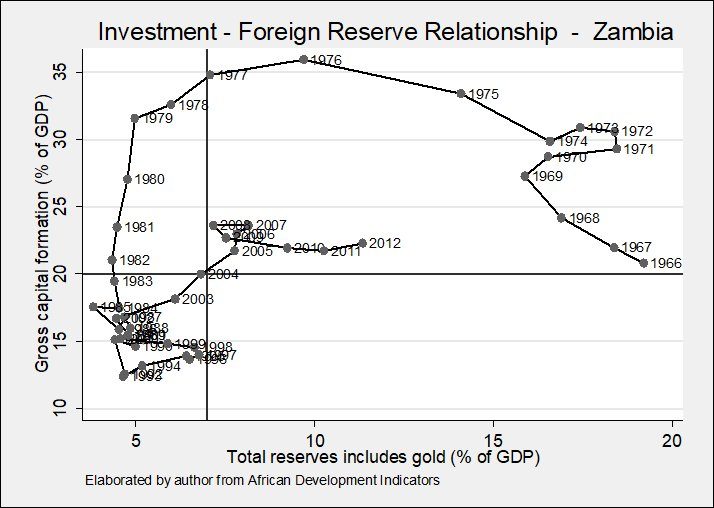

His very long-term view of development. He had a chapter in an edited book a couple years ago that looked at long-term business cycles and state capacity. He plotted capital accumulation and investment, and showed just how dependent African economies were on external price swings and long-term business cycles. He showed how much state capacity is tied up in these business cycles. Here are some examples from the book:

These boom and bust graphs capture clearly the imperative of structural transformation and the need for economies to mobilise their own domestic resources and move out of more vulnerable parts of the global economy. But they also help us to see just how near-sighted so much of African political economy has been. Scholars have tended to get trapped in their own era and confined to one quadrant of the graph, explaining what is happening in the here and now- instead of trying to explain the very long-term. What would African political economy look like if we instead focused on the very long-term? How do we break out of these quadrants?

Thandika was the preeminent African economist of his generation, but by virtue of outrageous fortune, he was also a Swede and a Scandinavian. This dual identity made him special. He had seen with his own eyes, the crucial role that social policy could play in shaping the social impacts of economic growth and development. His work at UNRISD on transformative social policy demonstrated that social welfare and public investment were not just about redistribution and poverty reduction but also about productivity- and ultimately making people the basis of capital accumulation within the economy. In a time when technology and firm restructuring are shifting the locus of accumulation out of labour, we need his ideas more than ever before.

Thandika’s dual identity also made him suspicious of attempts to portray African development as something exceptional or aberrant- or the idea that African development somehow needed its own theoretical frameworks. To him, the challenge of decolonisation was not about coming up with different explanations and theories to explain African countries, but rather to deconstruct established theories that had been gleaned from the rather idiosyncratic experiences of Europe and North America- or East Asia. In other words, he tried to show that African countries were not somehow dysfunctional, but rather that mainstream development theory was itself dysfunctional, unable to explain things because it was too provincial. Because of Thandika, I have come to see just how idiosyncratic European or American development experiences have been. Thandika was a global intellectual who wanted African experiences to be put into conversation with the rest of the world. He didn’t want Africa to be treated separately.

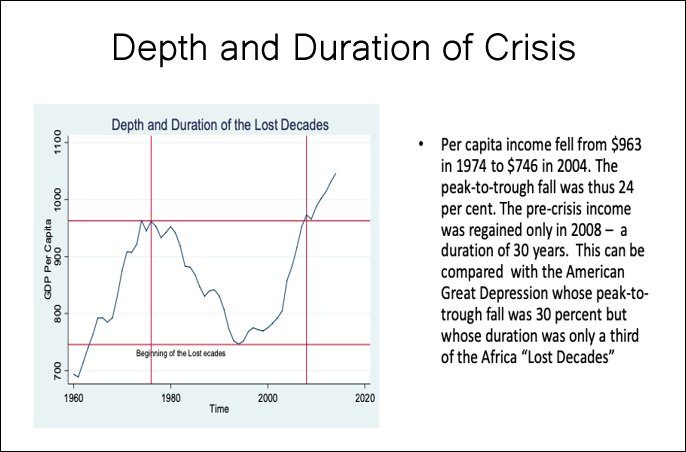

Thandika was working on a book at the time of his passing. He was trying to compare African experiences of structural adjustment with that of the Great Depression in the 1930s. This is a slide from one of his lectures a couple years ago:

He wanted to write about these ‘lost decades’ because I think he found it kind of amazing and shocking that African economies had been allowed to collapse so dramatically in the wake of the Debt Crisis- the pauperisation of the Middle Class, the shocking deconstruction of African higher education (and therefore, intellectual autonomy), and the collapse of African capitalists and business skills. Instead of rethinking industrial policy and addressing problems of excess capacity, businesses, public services and communities were just allowed to go bust. I have been thinking A LOT about Thandika’s book project in the midst of the current pandemic- just how much and how far the governments of high-income countries are willing to go to protect the productive capacity of their economies. What would African developmental history be like today if the same was done back then too? What would have been saved? What didn’t have to be lost?

There are millions of any lessons and insights that Thandika bestowed upon me, and I am sure they will all rise to the surface as I continue to remember him. I hope he realised how much he meant to all of us, and how effective a teacher he was. I will miss him so very much.

A few years ago, we organised a workshop on the ‘Youth in Africa’ and we asked everyone to find an old photo of themselves as a ‘youth’. This is Thandika at age 20, when he helped establish an anti-colonial newspaper in Malawi. What a life he led!