For several centuries - between the

15th and the early 19th centuries - mercantilist theories dominated the

attitude to trade in Europe. This was the belief that an economy that

had positive net exports (through exports being greater than imports)

would be wealthier because it would lead to an inflow of bullion, or assets,

and thereby increase its economic strength. This approach led to economic

policies designed to increase exports and suppress imports, trade wars,

and even the colonial wars that were crucial to ensuring markets for the

various European powers.

There were of course many flaws of mercantilist theories, most notably

the confusion of bullion with real economic wealth, the lack of recognition

of the various benefits of greater trade independent of the trade balance,

and the failure to perceive that the purpose of increasing exports is

to be able to import more, and thus raise the level and variety of consumption

in the society.

For a relatively long time, mercantilist arguments have been discredited.

But recently, a new form of neo-mercantilism has emerged and has propelled

the economic models of the two economies that are increasingly seen as

the most successful and potentially powerful in the world: China and Germany.

Mercantilism - the obsession with net exports - is often seen as identical

with export-led growth, but in fact the two are not the same. It is possible

to have exports as the basic engine or driver of growth without necessarily

running a trade surplus. All that is required is that export demand becomes

a catalyst for growth in the rest of the system and generates additional

demand.

Indeed, some of the classic examples of recent export-led growth, such

as the East Asian “dragons” or the Southeast Asian economies, generally

ran trade deficits during their period of high export-led growth. Even

China's trade surpluses are of relatively recent vintage, since the country

had trade deficits during the period of rapid export growth from the early

1980s to the late 1990s, and only started having large trade surplus in

the early part of the 2000s.

However, for the last decade in particular, both China and Germany have

been increasingly reliant on a strategy of growth that requires pushing

out more and more net exports. This in turn has required suppressing domestic

wages and consumption. In China the consumption to GDP ratio fell from

46 per cent of GDP in 2000 to less than 36 per cent in 2007, while in

Germany it fell from 60 per cent to 56.5 per cent in the same period.

Why would such a strategy be attractive at all? After all, no one really

still believes that an inflow of bullion (or a net accumulation of financial

assets, which amounts to the same thing) is of great intrinsic value for

an economy. It could be argued that the current strategy is based on a

different notion of the gain; one which recognizes the absence of full

employment and seeks to use trade as a means of maximizing employment.

Thus net exports are valued because they involve more productive jobs

at home and less leakage of jobs through imports. To that extent, this

is also a form of beggar-thy-neighbour economic strategy, since it involves

creating or preserving jobs in your own country at the expense of jobs

in your trade partners.

This argument too is essentially fallacious, because it does not recognise

that while trade can affect the pattern of employment, the aggregate level

of employment is determined by macroeconomic policies. The possibility

of employment in non-tradable activities making up for employment losses

through trade (which would have to be the result of active government

intervention as well) is not considered.

Despite this, the urge to generate trade surpluses has become an important

plank of the overall economic strategy in both countries. It is possibly

even more marked in Germany than in China, which has seen some recent

moves to develop the home market.

Even more than export-led growth per se, such a strategy involves a fallacy

of composition, in that all countries cannot pursue it. Indeed, the dependence

of the surplus economies on the existence of other countries that are

simultaneously running deficits is only too obvious. In the recent past,

that has come from a combination of one large global player (the US economy,

which has served as the engine of growth for much of the rest of the world)

and a number of smaller economies running smaller deficits financed by

capital flows.

This gives rise to a classic dilemma of mercantilist strategy, which is

evident in an exaggerated form today for the neo-mercantilist economies:

they are forced to finance the deficits of those countries that would

buy their products, through capital flows that sustain the demand for

their own exports. Thus it is no accident that China and Germany are both

large investors in the US and purchasers of US Treasury Bills, or that

German banks are heavily implicated in lending to the now-fragile deficit

economies in the European Union.

Despite these contradictions and dilemmas, such a strategy can certainly

be successful for a while, and this can be true even over the economic

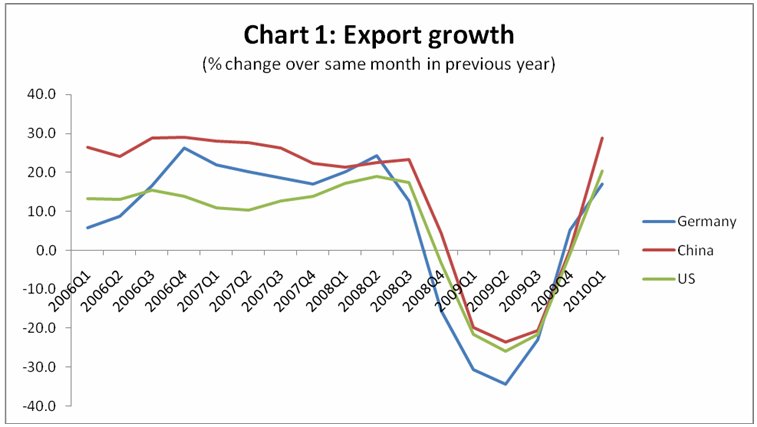

cycle. This is evident from Chart 1, which shows how both China and Germany

experienced very sharp declines in export growth in the wake of the recent

global crisis, but have since rebounded sharply.

(It should be noted that all charts refer to merchandise trade only.)

Interestingly, Chart 1 also shows how the United States

economy had been showing reasonably high export growth before the crisis

and how its export growth has also revived (largely related to dollar

devaluation) in the most recent period.

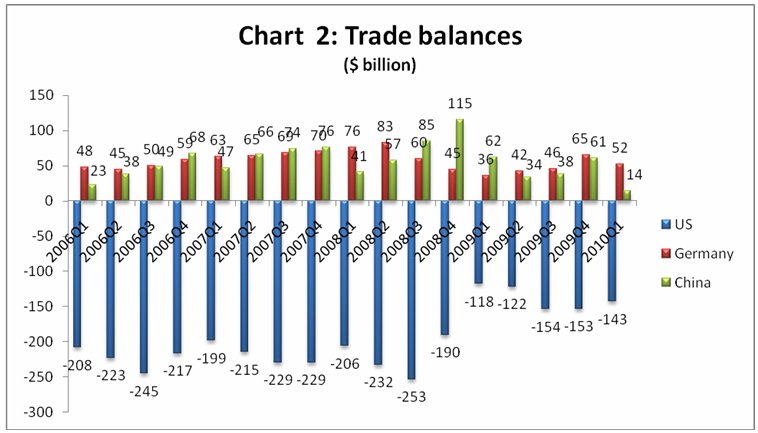

Chart 2 indicates how the trade surpluses of these two mercantilist economies

are related to the deficits run by the US. The US deficit is obviously

much larger than the combined surpluses of these two countries, but as

it has shrunk slightly in the wake of the crisis, so have their surpluses.

Nevertheless, both countries have maintained the tendency

to generating trade surpluses, alough there has been some shift within

China. In Germany, the ability to impose wage restraint throughout the

period of economic boom and rising labour productivity were remarkable

in their scope, and critical to the enhanced competitiveness of the economy.

During the crisis, employment levels fell relatively little, not only

because of the existence of automatic stabilisers that provided a countercyclical

cushion for the economy, but also the willingness of German workers in

export industries to accept effective wage cuts rather than lose employment.

In any case in Germany, a significant part of the export surplus is generated

from trade with other partners in the Euopean Union (EU). Intra-EU trade

accounts for around two-thirds of total EU trade, and an equivalent part

of German trade as well. Chart 3 shows how movements in Germany's trade

surpluse have been closely mirrored by movements in the aggregate deficit

of all other EU countries.

It is this misalignment within Europe that is at the

heart of the economic problems faced by many deficit countries in the

region today. There is a basic difference between price levels in Gemany

and most other EU members, resulting from the fact that Germany has been

able to keep wages nearly stagnant even with rapid labour productivity

increases, while other countries are not able to let the gap between wages

and productivity widen to that extent. This means that prices of many

goods and servies are significantly lower (sometimes by as much as one-third)

in Germany compared to most other European economies.

Remarkably, therefore, there are real exchange rate mismatches within

a common currency area. Obviously this reflects another significant failure,

that of the European Single Market to ensure price arbitrage of traded

goods, or wage equalisation through the movement of labour.

What is more significant for present purposes is that such mismatches

cannot continue indefinitely. Already the deficit countries in Europe

- not only those whose goverments' bond markets are in difficulties but

others as well - are being forced to cut down on imports through very

severe austerity measures that are reducing both output and employment.

Ironically, such moves are being strongly pushed by the German government

inside the EU, even though this is likely to rebound adversely on the

German capacity to generate export surpluses.

In the US, the external adjustment will also clearly occur, whether through

exchange rate movements or increased protectionism, or in any other manner.

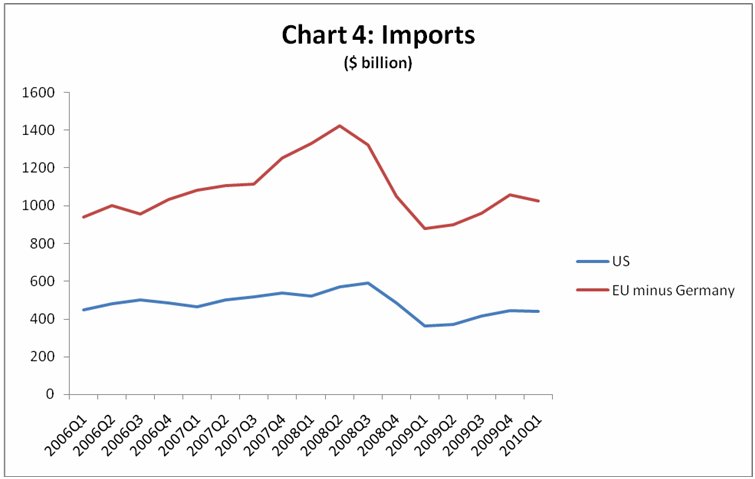

Chart 4 suggests that this process is already underway: although import

levels of both the US and non-Germany EU have recovered slightly from

the trough of early 2009, they are still far below the earlier peaks and

also appear to be levelling off despite the recent output recovery.

So, while the neo-mercantilist strategy can be apparently successful for a while, it is likely to come up against both internal and external constraints. Internally, the potential for suppression of wage incomes and domestic consumption will meet with political resistance. Externally, deficit countries will either choose or be forced to reduce their deficits through various means. In either case, the pressures to find more sustainable sources of economic growth, particularly through domestic demand and wage-led alternatives, are likely to increase.