Well before the financial crisis broke

out so violently in the US and caused ripple effects all over the world,

most people in developing countries were already reeling under the effects

of dramatic volatility in global food and fuel markets. In 2007 and 2008

prices of most primary commodities first increased very rapidly, to a

degree that was completely unwarranted by actual changes in global demand

and supply. Then they collapsed, from peaks in May-June 2008, at even

more rapid rates than their previous increases. But in many countries

the fall in global prices was not associated with a fall in prices paid

by consumers, while the actual producers (such as farmers) rarely benefited

from the price increases.

It is now quite widely accepted that financial activity - specifically

the involvement of index investors - was strongly associated with these

dramatic price movements. Commodities emerged as an attractive alternate

investment avenue for financial investors from around 2006, when the US

housing market showed the initial signs of its ultimate collapse. This

was aided by financial deregulation that allowed purely financial agents

to enter such markets without requirements of holding physical commodities.

This generated a bubble, beginning in futures markets that transmitted

to spot markets as well.

Thereafter - even before the collapse of Lehman Brothers signalled the

global financial crisis - commodity prices started falling as such index

investors started to withdraw. The global recession that was evident from

mid 2008 led to perceptions that commodity prices would not firm up any

time soon. While this contributed to fears of deflation in the context

of liquidity trap conditions, this was even seen to be an advantage especially

for food and fuel importing developing countries, whose import bills would

be reduced accordingly.

But while the collapse in commodity prices after the recent peak was sharp,

it proved to be quite short-lived. Most important commodity prices - especially

food and oil prices - have been rising from early 2009, even before there

was any real evidence of global ''recovery''.

Chart 1

Chart 1 shows that global food prices, which nearly doubled between June 2007 and June 2008, fell very sharply thereafter and were back to the June 2007 level by December 2008. But thereafter they have been rising once again, such that the increase between December 2008 and November 2009 has been more than 16 per cent on average across all food commodities. Agricultural raw materials prices did not rise as quickly and fell more in the second half of 2008, so their recent price increase has been sharper, close to 35 per cent in the seven months between May and November 2009. But this means that they are on average only just back to the level of two years earlier.

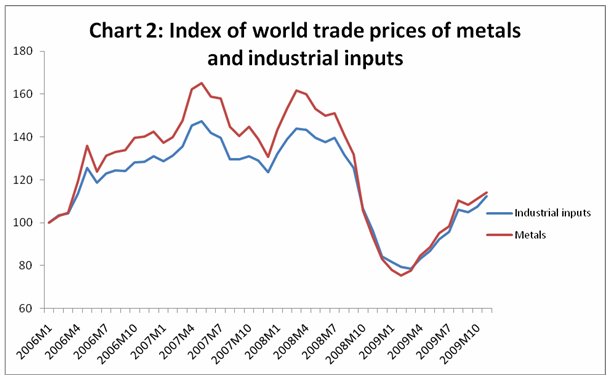

Chart 2

Other non-agricultural primary commodities - metals

and other industrial inputs, showed less price increases during the 2007

commodity boom, more volatility over the course of 2008 and sharper falls

thereafter, so that by the beginning of 2009 their prices were below those

of January 2006 (Chart 2). But these prices have exhibited particularly

pointed recovery since then, increasing by more than 50 per cent in the

case of metals between March and November 2009, and by 43 per cent in

the case of other industrial raw materials.

Of course energy prices are particularly crucial, and here the recent

trend in both all fuel prices (including coal) and only petroleum prices,

has been quite marked as well. Chart 3 shows a picture of great volatility,

but the extraordinary price increases of 2007 to mid 2008 and the subsequent

fall tend to reduce the attention to more recent trends. Thus, in the

eleven months of 2009 for which the data are now available, fuel prices

have increased by 53 per cent and oil prices have increased by 88 per

cent. In any other period such increases would be the object of widespread

attention and the subject of endless commentary. But because we live in

such ''interesting times'', with a recent history of even greater and

more rapid increase and decrease, they have largely gone unnoticed.

Chart 3

Why is this happening? And what does it portend for

the future? It was noted earlier that the recovery in most primary commodity

prices actually predated the global output recovery. As was the case in

the previous price surge of 2007-08, these recent price increases are

unlikely to be related to any real economy changes in demand and supply.

Despite some supply shocks in particular crops, according to the FAO most

agricultural goods in 2009 showed approximately the same demand-supply

relationships that existed in the previous years, with no force making

for any significnt upward or downward price trend. So if prices are increasing,

it must be because of the effect of expectations combined with heightened

speculative activity in commodity markets, especially in commodity futures.

Indeed, there is no reason for such speculation to be curbed at present;

if anything, the low interest rates that are being maintained by most

major economies as part of the recovery package, combined with the immense

moral hazard generated by the large financial bailouts, are likely to

have made the appetite for risky behaviour much larger. Both gold and

other primary commodities are once again emerging as prime areas of interest

for financial institutions, and some of the large (and succcessful) financial

players such as Goldman Sachs are expanding or opening new commodity investment

sections.

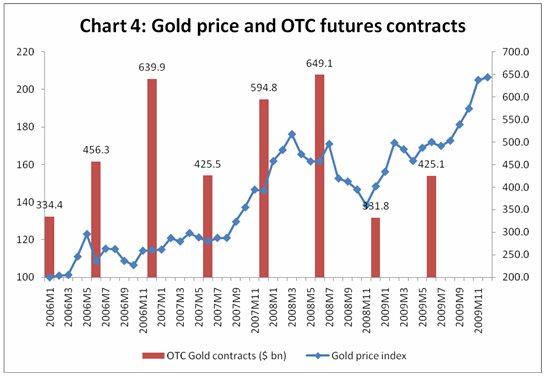

Chart 4

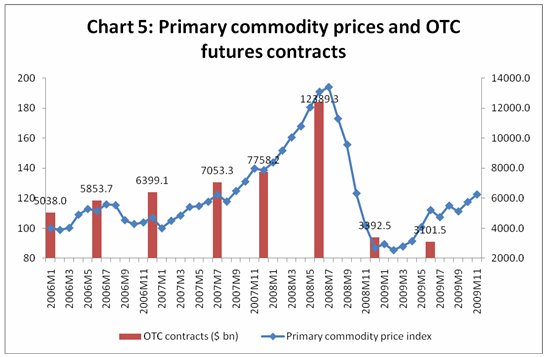

Chart 5

As Charts 4 and 5 indicate, the value of OTC (over the counter) futures

contracts in both gold and other commodities has tended to track spot

price movements. Since OTC contracts do not occur in regulated exchanges

(and in any case effective regulation that would constrain speculative

activity in commodity futures is not yet in place in any of the major

financial centres) such activity still has the potential to cause wild

swings in commodity prices that are not justified by any fundamentals.

This creates a piquant situation for economic policy. In macroeconomic

terms, the global threat of deflation is still greater than that of inflation,

especially because the financial crisis is far from resolved or even properly

dealt with and is bound to result in new problems in real economies sooner

rather than later. However, both the nature of the recent recovery and

the policy response to the crisis (which has provided more liquidity without

adequate control or regulation) suggest that primary commodities may well

witness a price surge once again.

Such price surges have huge negative implications for developing countries.

Because they are the result of financial activity, they typically do not

benefit the direct producers who may be resident in the developing world.

But they cause huge damage to consumers of food and other essential items,

typically the poor in developing countries who are the worst affected

as the prices of necessities increase even as their employment and wages

continue to languish.

If these very adverse effects are to be avoided, financial regulation

to curb speculative activity in commodity markets must become an urgent

priority at both national and international levels. The governments of

large developing countries that are now beginning to flex their muscles

at various international fora would to well to recognise the critical

urgency of such measures, if they really want to benefit their own people

in international negotiations.