The

framework agreement for the Doha Round of trade negotiations

crafted by the General Council of the WTO has been

described as a breakthrough that would eliminate billions

of dollars in farm subsidies. According to Celso Amorim,

Foreign Minister of Brazil, "Obviously, developing

nations did not get everything they asked for in Geneva.

But the overall direction is clear: This is the beginning

of the end to export subsidies; the stage is set for

a substantial reduction in all types of trade-distorting

domestic support; market access negotiations will

open up new opportunities for trade, without prejudice

to the needs of developing countries." This viewpoint

has been echoed by the Indian delegation to the talks

as well, which has returned home with claims of a

"victory" that helps protect the interests of the

developing countries.

The upbeat official assessments from Brazil and India

are expected since they were part of the group of

five countries that extracted an agreement out of

a situation in which none was in sight. What is interesting,

however, is the nature of the remaining membership

of what has come to be identified as FIPs, the group

of "five interested parties". It includes the US and

the EU (representing the developed countries) and

Australia (representing the Cairns group of agricultural

exporters). If Cancun had seen the birth of the G-20

group of developing countries, which was a potentially

potent developing country forum formed to scupper

the efforts of the US and the EU to push through a

blatantly unjust launch framework, Geneva witnessed

the emergence of FIPs. India and Brazil broke ranks

with the G-20 to join "by invitation" the FIPs group.

The role of the FIPs group in generating a consensus,

through discussions on the changes to be incorporated

in the original July 16 draft framework, is now widely

accepted. On 29 July 2004, WTO Director-General Supachai

Panitchpakdi welcomed an agreement on the agriculture

text reached overnight by ministers from the FIPs

group as a key first step towards a consensus. Crucial

to the consensus, however was the ability of the FIPs,

especially Brazil and India, to win the support of

other developing countries, despite their criticism

of the process which largely involved discussions

among the five FIPs members. This they were able to

do, despite the fact that the annexure on non-agricultural

market access (NAMA) does not take the framework agreement

any further than the much criticised Derbez draft.

It must be said, however, that compared with what

was sought to be pushed through at Cancun the Geneva

framework agreement does reflect a substantial advance.

The two major advances are in the areas of agriculture

and the so-called Singapore issues. With regard to

the latter, three of four contentious new issues that

the developed countries wanted included in the Doha

Round, namely, investment, competition policy and

government procurement, have been dropped from the

agenda.

In agriculture, the framework binds the developed

countries into doing away with direct and indirect

subsidies provided to their exports. It also obtains

a promise of substantial reduction of domestic support

provided to their farmers. This primarily comes in

the form of an agreement to substantially reduce,

based on negotiations, the sum total of Final Bound

levels of the Aggregate Measure of Support (AMS),

de minimis (or minimal acceptable) support and Blue

Box measures. Such reduction is to occur through a

tiered-formula involving larger reductions by those

currently providing higher levels of support, leading

to some "harmonisation" of support levels. In particular,

the framework requires that there would be a minimal

reduction in such support to 80 per cent of pre-existing

levels in the very first year and throughout the period

of implementation. Finally, while a major compromise

in the form of the continuation of the Blue Box has

been made, a promise to cap Blue Box support at 5

per cent of the value of production has been extracted.

In its proposal for improving market access, the new

WTO draft framework retains the concept of a tiered

tariff reduction formula originally introduced in

the Harbinson's text. This formula calls for deeper

tariff cuts for products with higher levels of protection.

This formula aims to harmonize the tariff structure

and address the issue of tariff escalation. However,

there are some exemptions allowed in the new text.

It has a provision for lower tariff cuts for an "appropriate

number" of 'sensitive products' for all countries.

There is an apprehension that the clause on "sensitive

products" will be used by developed countries to protect

their uncompetitive sectors. Early indications suggest

that USA is likely to designate sugar as a sensitive

product. However, in this sphere, there are some important

gains in terms of special treatment for developing

countries. The agreement explicitly recognises the

need for Special and Differential Treatment for developing

countries – in terms of the quantum of tariff reduction,

tariff rate quota expansion, number and treatment

of sensitive products and the length of the implementation

period. In particular, in parallel with the right

of developed countries to designate certain products

as "sensitive", developing countries have the right

to identify an appropriate number of "Special Products",

based on criteria of food security, livelihood security

and rural development needs, which would be eligible

for more flexible treatment. Finally, the framework

provides for a Special Safeguard Mechanism against

disruptive imports, the details of which are to be

worked out.

It must be noted that all of these gains are not really

commodity specific, but apply to agricultural products

in general. In an area like cotton, where some developing

countries, especially from the ACP bloc, had a special

interest and where their demands were specific, the

framework agreement recognises the vital importance

of this sector to certain LDC members and promises

to work to achieve ambitious results expeditiously,

but within the parameters set out in the Annex on

agriculture. The less-developed among the developing

are therefore not as upbeat regarding the framework

agreement.

Despite the positive features of the framework agreement

outside of NAMA and its advance relative to Cancun,

doubts are now being cast on whether much has been

achieved by way of substantial reductions in support.

One area where this is indeed true is export subsidies,

which are to be eliminated even if in a phased manner.

But this was in many senses inevitable. Recent WTO

rulings had made clear that many of these were unsustainable

even under current rules, making their phase-out a

prerequisite for any agreement whatsoever. This was

an area where the need for revised rules had been

conceded. What the EU, that offers such support, managed

to extract in return for a phase-out was the promise

of parallel concessions in the form of reductions

of implicit subsidies on export credits, for example,

from the US. The area of contention was of course

domestic support, which accounted for the bulk of

the more-than-$300 billion support that the OECD countries

provide to their farmers allowing them to dominate

the $600 billion global market for agricultural commodities.

It is here that the developed countries have managed

to retain much of their leverage, unless subsequent

negotiations force them to offer much more than provided

for in the framework agreement.

Early in the negotiations, there were two major gains

in the agriculture area which the US and the EU managed

to obtain, which are taken for granted now. The first

was the "preserve-as-is" attitude to permitted Green

Box support measures. The second was the continuation

of the Blue Box, which was to be phased out at the

end of the Uruguay Round implementation period.

These gains have only been strengthened in the final

framework agreement. The agreement clearly states

that the "basic concepts, principles and effectiveness"

of the Green Box remain untouched, subject to a review

to ensure that its trade-distorting effects are 'minimal'.

Further, not only can members take recourse to existing

forms of Blue Box support, but new measures can be

negotiated subject to the condition that such payments

will be less trade-distorting than AMS measures. Clearly

then, the idea is to maximise support which is provided

to agriculture by offering an appropriate combination

of Green Box and Blue Box support, rather than through

measures conventionally defined as trade-distorting.

The real concession provided by the OECD countries,

if any, is the promise to reduce aggregate support

in the form of the sum total of current levels of

bound AMS rates, de minimis support and Blue Box support.

How much of a concession does this involve in the

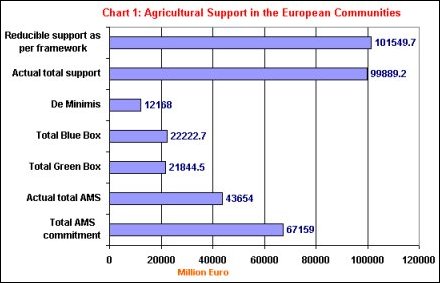

case of the EU? Chart 1 provides details of the officially

recognised forms of support provided by EU governments

to their farmers. The first feature to note is that

Green Box support in 2000/01 already accounted for

more than one-fifths of total support provided in

the EU. This is an area into which other forms of

support can be moved to bypass any conditions that

the new framework may set.

|

|

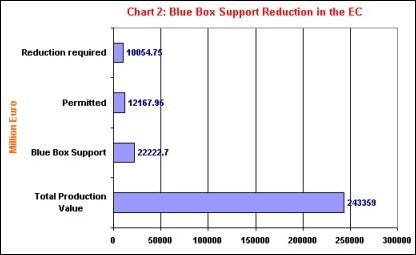

But that is not all. In 2000/01, at the end of the

Uruguay Round implementation period, the bound AMS

support that the EU was eligible to provide was Euro

67.2 billion. However, as a result of the reform of its

Common Agricultural Policy, the actual support provided

in the form of recognised AMS measures amounted to only

Euro 43.7 billion (Chart 3). Permitted de minimis

support, at 5 per cent of the value of production,

amounted to Euro 12.2 billion. And total Blue Box

support in that year amounted to Euro 22.2 billion or

9.13 per cent of the value of agricultural production.

|

|

Thus the total value of support subject to the

minimal 20 per cent reduction commitment agreed on so

far, which equals the total of bound AMS, plus de

minimis support, plus Blue Box support, stood at Euro

101.6 billion. The framework agreement requires that at

the minimum this is brought down to 80 per cent of that

level or down to Euro 81.2 billion. However, since the

actual AMS is less than the bound, commitment level, the

level of actual as opposed to bound-AMS based total

support plus de minimis support, plus Blue Box support

stood at only 78.0 billion in 200/01. Thus in terms of

the aggregate commitment provided for in the framework

agreement the EU does not have to make any change.

Change would be required only if negotiations are able

to extract more than a 20 per cent reduction commitment

or ensures that commitments in individual areas add up

to a reduction that is larger.

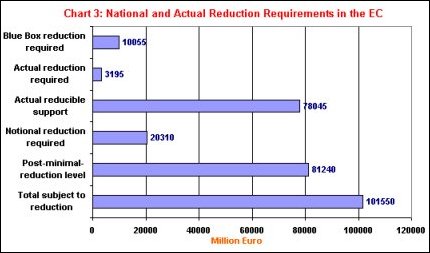

However, there is a 5 per cent of value of

production cap on Blue Box support, which implies that

such support in the EU would have to be brought down by

Euro 10 billion from Euro 22.2 billion (Chart 2). This

reduction is not guaranteed, since the framework

agreement provides for the possibility of some

flexibility in cases where "a Member has placed an

exceptionally large percentage of its trade-distorting

support in the Blue Box". Further, if Blue Box support

can be restructured and rendered in the form of Green

Box measures, the required reduction could be shifted

and added to the Euro 21.8 billion of Green Box support

that the EU provided in 2000/01. In sum it can get away

with no reduction whatsoever to meet its proposed new

minimal commitments. In a worst case scenario, it would

have to make a less-than-10 per cent reduction in total

support to meet the requirement set thus far by the

framework agreement.

|

|

It appears that domestic subsidy reduction

commitments are not going be high for USA also. If one

looks at the reduction commitments of USA, its total AMS

commitment level for 2000 was $ 19,103.3 million and

maximum de minimis level of support for that year was $

9476 million[1]. So,

calculations show that according to the current formula,

USA will have to reduce its subsidies to $ 22863.45

million (80 percent of AMS plus de minimis) from their

current level of AMS plus used de minimis support of $

24143.26 million. This amounts to only about 5.3 percent

reduction from their current (trade distorting) support

level[2].

However, AMS accounts for only about a quarter of

total domestic support given to the farm sector in the

USA. Green Box subsidies are the most dominant form of

domestic support for the agriculture sector in that

country. For example, in 2000, total Green Box subsidies

given to the farm sector was more than $ 50,000 million,

while the AMS provided in the same year by USA is around

$ 16,000 million. As there is no reduction commitment on

Green Box subsidies, USA will be allowed be continue and

increase its massive Green Box support programmes.

Additionally, the WTO draft has incorporated provisions

for countries to introduce Blue Box subsidies. This will

provide USA the option to introduce Blue Box support up

to 5 percent of the value of its agricultural

production. The Bridges Weekly Newsletter suggests that

this clause will allow the US to notify its

counter-cyclical payments under the 2002 US Farm Act as

Blue Box measures.

The commitment to reduce and eventually abolish all

forms of export subsidies including "export credit

guarantees or insurance programmes with repayment

periods beyond 180 days" is considered to be one of the

highlights of the new draft. A look at USA's export

credit schemes show that there are four export credit

programmes (Table 1) and apart from the Supplier Credit

Guarantee Programme, other schemes are targeted towards

longer term export credits. It also appears that the WTO

ruling is likely to affect the GM-102 scheme, which is

the largest of the four programmes. However, it must be

kept in mind that the end date for the reduction of

export support schemes is yet to be decided and the

effectiveness of the new draft will depend, to a large

extent, on the negotiated deadline. Also past experience

with implementation of WTO rules show that there is a

strong possibility that longer term export credit

schemes will be tweaked to adjust to the WTO ruling.

Therefore, at this point it is difficult to judge how

effective these new WTO rulings will be to discipline

huge US export credit outlays which amounted to about $

3.34 billion in 2003.

|

Table 1. Details of Export Credits Schemes

of USA |

|

Export Credit Programmes |

Duration |

Outlays (1999) |

|

GSM-102 Export Credit Guarantee Program |

Up to 3 years |

$ 3,000 millions |

|

GSM-103 Intermediate Export Credit Guarantee

Program |

Up to 10 years |

$ 44 millions |

|

Supplier Credit Guarantee Program |

Less than 6 months |

$ 46 millions |

|

Facility Credit Guarantee Program |

unspecified |

- |

|

Source: USDA website |

|

Memo Items |

2002 |

2003 |

Total US export credits

(GSM 102, GSM 103, SCGP) |

$ 3.22 Billion |

$ 3.39 Billion |

|

Source: Oxfam

(2004) |

|

Thus, even though in the agricultural trade area the

framework agreement does appear to both extract large

concessions from the developed countries and accommodate

the interests of the developing countries, it leaves

more or less untouched both the framework of domestic

support in the developed countries involving Green,

Amber and Blue Boxes as well as the magnitude of

domestic support that is being provided. Any change here

would involve more "give-and-take" in the negotiations

that are to follow, and considering the structure of

power in the world economy it is likely to involve more

take than give by the developed countries.

It is in this light that the formation of the FIPs

needs to be assessed. History suggests that two

different factors influence the extent of liberalisation

that the evolution of the trade regime implies: first,

multilaterally agreed, monitored and implemented

measures, which define the minimal level of

institutionalised trade reform; second, the regionally,

bilaterally or unilaterally implemented measures of

liberalisation, shaped by domestic and international

compulsions. It hardly bears stating that, in developing

countries, in most areas the liberalisation implied by

the latter go far beyond those mandated by the former.

Multilateral rules most often institutionalise the

levels beyond which countries cannot retreat from

existing degrees of liberalisation, rather than

requiring them to undertake further liberalisation.

In most less developed countries markets are hardly

protected and already dominated by transnational

industrial and agri-business firms. The result is that

for most of the less-developed developing countries, the

principal issues in trade talks are the degree to which

they can legitimately seek out markets for their primary

products in the developed or other developing countries

and the extent of special treatment they obtain to do

this given their underdeveloped status. However, since

the role of these countries in world markets are

limited, except in the case of particular primary

commodities, such as cotton for example, they ability to

get themselves heard is also limited. The implications

of these features are that they have little to defend,

and more to gain from others. Their need for a

multilaterally agreed set of possibilities is far

greater. They must finally go along with what is on

offer.

As compared with this, the more developed of the

developing countries like Brazil and India have far more

to defend, in both agricultural and non-agricultural

markets, and they are or can be important players in

global export markets for agricultural, manufacturing

and service sector exports. This makes their endorsement

of any process of trade liberalisation, which is crucial

if a consensus has to be forged, more uncertain. On the

other hand, if their endorsement is obtained, bringing

in other developing countries is easier. This includes

major powers like China whose dependence on world

markets and the huge concessions they have already

given, makes any agreement better than none. It also

includes countries like Thailand and the Philippines,

whose dependence on the US and/or EU is too strong to

permit dissent. Thus, FIPs was clearly created to obtain

an endorsement from India and Brazil, and other

similarly placed developing countries, and to use that

endorsement to bring all else in line. The

developed-country camp's climb down on the irrationally

hard positions it took on agriculture in Cancun,

including the promise of special and differential

treatment especially in the form of Special Products and

new possibilities in areas like services for India

helped clinch that endorsement outside the formal

negotiations.

But this does not imply that any major victory has

been won, not merely in the NAMA area but also in

respect of domestic support for agriculture. If

concessions have to be won in this area a high degree of

solidarity in future negotiations within the

developing-country camp is needed. It is that solidarity

that the formation of FIPs undermines. However, the

overall gains are seen by India as justifying its claims

of a victory for developing countries and itself and of

the correctness of its participating in the FIPs

discussions. In the official view of the Indian

delegation, India's participation also helped protect

India's (short-term) interests. According to this view,

the grouping helped present to the US and EU the minimal

requirements of the more developed of the developing

countries, by providing a negotiating channel between

the dominant powers and the G 20. It helped ensure that

the basis for a minimal set of concessions in the

agricultural area was formally accepted by the developed

countries. It helped prevent the developed-country bloc

from offering damaging special concessions to the G-90,

the group of less-developed developing countries in

order to win their support for a framework agreement

that works against the interests of countries like India

and Brazil. For example, the developed country

suggestion that all countries should provide duty free

access to global, non-agricultural export markets to the

G-90 countries, could have paved the way for them to be

used as locations from which developed country

transanationals could access markets in the more

developed among the developing countries. And, as Indian

officials informally argue, the formation of FIPs helped

prevent Brazil – ostensibly the "weak link" in the

developing-country camp – from breaking ranks and

striking a separate deal with the developed countries.

These claims of success notwithstanding, the

creation of FIPs, the inclusion of India, along with

Brazil, in the grouping and the nature of the framework

agreement that FIPs was instrumental in forging, has

weakened the developing country camp, which G 20 was

expected to strengthen. Even at the framework stage, in

return for minimal concessions, the US and the EU have

managed to obtain significant agricultural and non

agricultural market access commitments in the form of

to-be-negotiated, non-linear tariff reductions from the

developing countries. India and Brazil have ignored the

implications of these likely reductions, because they

have unilaterally been reducing their tariffs. But when

bound rates are reduced from there current relatively

high levels, protection to prevent market disruption

would depend on the yet-to-be-elaborated Special

Products provision.

When the full implications of these reciprocal

market access concessions are fully analysed, the losses

that developing countries have suffered may prove

substantial relative to the gains assessed relative to

the hard positions adopted by the developed countries in

Cancun. This would show that even till now the

negotiations have not been a cake-walk for the

self-designated and much-resented leadership of the

developing world. And the process has just begun.

Developing countries may have moved one step forward

from Cancun, but it is not yet time to celebrate.

August 17, 2004.

[1] De minimis

is taken as 5 percent of the value of agricultural

production, USA currently does not use blue box

subsidies

[2] These data are taken from USA's

submission to WTO

|