Donald Trump’s top economic advisor claims the President has weaponised tariffs to ‘persuade’ other nations…

Financial Sanctions vs the US Dollar Radhika Desai

Not only are US and EU sanctions illegal under the UN charter, the US freezing of Russia’s reserves is simply theft. It smacks not of independence either of institutions or the legal system, but of their profound politicization, nay criminalization, in US interests, writes Valdai Club expert Radhika Desai.

Things are really bad when employing the only means left to stave off disaster brings it closer. That is the story of the most powerful of the numerous sanctions the US has used, and convinced EU countries to use, against Russia in the war the West is waging against it over Ukraine, the freezing of its central bank reserves.

That war is the current phase of US wars, military and hybrid, to stall and reverse the slide in its (attempted) world dominance. They have targeted countries who merely assert their right to manage their economies and their international economic and political relations on their own terms, rather than those convenient to and/or dictated by the US. Currently, over the past decade or so it has been waged increasingly through sanctions and, after the US’s military debacle in Afghanistan, today exclusively so.

US and EU sanctions are ‘intended to bring down the Putin regime’ in British Prime Minister Boris Johnson’s words or to wage ‘an all-out economic and financial war’ for ‘the collapse of the Russian economy’ in those of French economy minister Burno Le Maire’s words or to ‘take out’ President Putin, in US Senator Lindsey Graham’s words. Prima facie, the freezing of Russia’s central bank’s reserves has been spectacularly effective. It has sent the ruble plunging and forced the Russian central bank to jack up interest rates to 20 percent. It has even contributed directly to a herd of corporations stampeding out of Russia. They cited ethical concerns. However, they are actually fleeing an ‘environment of such legal and financial hostility’ that raises more fundamental concerns. Will they unknowingly end up doing business with a sanctioned individual? Will they get prosecuted? Will they get paid? They might still earn profits in Russia, but can they get them out? Surely, with these developments, sanctions are well on their way to achieving their aims.

The Council on Foreign Relations’ Sebastian Mallaby certainly thinks so. In a recent column in the Washington Post, he grandly announced that ‘The West has invented a new weapon’, freezing a country’s reserves, which can ‘turn a financially sound economy into a basket case’. However, it is a mark of how delusional things are getting inside the beltway in Washington that practically every argument in Mallaby’s article is questionable.

True, nearly 60 percent of Russia’s vaunted $630 billion worth of reserves, stockpiled for the rainy day when it may not be able to access Western credit or for intervening in currency markets if there was undue pressure on the ruble are now unavailable in the country’s out of need, though not entirely, it would seem. However, it already seems unlikely that, as Mallaby claims, this will cost President Putin his reputation as a good economic manager, given his government’s vigorous response.

The seizure of Russia’s assets shows, Mallaby argues further, that the US no longer need fear its creditors as it once did, for instance, when it worried Japanese or Chinese would dump the dollar. However, powerful debtors have never feared creditors – Philip IV of France destroyed his creditors, the Knights Templar and Edward III of Britain defaulted against Italian banks, bankrupting them – and, in any case, the US has long claimed that it is the world’s bank and its debts are its creditors’ cash balances.

Mallaby’s core argument is that by denying creditors access to their assets, the US has destroyed the advantages of being a creditor. What is the point of having assets if you cannot access them when you need them most? ‘What matters’, he argues, ‘is having a financial system that commands global trust, based on an independent central bank and an independent legal system.’

There, however, lies the rub. By taking this action, and others that have led to this one, the US has demonstrated to a very attentive world that its central bank and legal systems are far from independent and its financial system is untrustworthy.

Not only are US and EU sanctions illegal under the UN charter, the US freezing of Russia’s reserves is simply theft. It smacks not of independence either of institutions or the legal system, but of their profound politicization, nay criminalization, in US interests. It also undermines (further) such ‘global trust’ as the dollar-denominated international financial system, run out of New York and London, enjoys. Worse, this is not unprecedented. The US has done it before, for instance, to Venezuela or Iran. Doing it to Russia, a much larger nuclear-armed permanent member of the United Nations Security Council, simply makes this aspect of US conduct more visible and a much larger number of governments and institutions wary.

Indeed, along with the other confiscatory sanctions applied to Russia and Russians, such a measure amounts, as Patrick Armstrong of Russia Observer put it, to the US saying to the world, ‘Put your money in our banks, we can confiscate it; put your assets in our territory, we can steal them; use our money and we can cancel it; put your yacht in our harbour, we can pirate it; put your gold in our vault, we can grab it.’ Some independence, some trust!

The fact is that the sanctions against Russia are part of a long-established pattern of US behaviour which has come into its own in the post-Cold War era. While the US imposed illegal sanctions of all sorts during the Cold War, they had limited effect given that the Communist Bloc offered sanctioned countries, such as Cuba, alternative trade, technology and investment relationships. Therefore, sanctions were not much use. After the Cold War, imposing legal UNSC-backed sanctions briefly became possible but after their horrific effects on the people of Iraq in the 1990s – cutting Iraq’s national income to 1/6th, and leading to over half a million child deaths due to malnutrition – became widely known, their use became profoundly illegitimate.

Thereafter, the search for ‘smart sanctions’, sanctions allegedly designed not to affect ordinary people, only the elites and their wealth – lighted on the US dollar and the financial system. As the country controlling most of the major structures of the dollar creditocracy that functions, faute de mieux, as world’s monetary system, the US could simply make it difficult for governments, central banks, financial institutions or individuals to conduct dollar transactions, effectively ejecting them from it. This weapon was first tried, we are told, by the Bush administration in cutting terrorist financing and it was observed that its effectiveness lay not just in compliance but in ‘overcompliance’: governments and financial institutions bending over backwards to stay away from even the whiff of transactions with sanctioned entities.

Thus, in the twenty-first century the way was open for the use of financial sanctions and, with US military power and geopolitical influence manifestly declining, US administrations began resorting increasingly to them in the wars that became necessary to avert that decline. Unfortunately, they have failed to even stall, let alone reverse, it. Reams of literature demonstrates that sanctions have proven quite ineffective. What is less widely discussed is that they are counterproductive, undermining, by weaponizing, the very dollar system that is the chief apparatus of US power.

Its modern, post-1971, form was already volatile, unstable and self-undermining, needing to rely on a series of financializations or asset bubbles that inevitably burst, causing great economic harm. This was already reducing the attractions of the systems for those whose participation in it was essential to its functioning. Now, by weaponising the dollar system, US authorities are only further undermining it.

Unable to supply credit, as Imperial Britain had done in the days when the pound sterling was the major currency, the US has always supplied the world with dollars in the form of debt, essentially borrowing money from the rest of the world in dollars. This method was always subject to the Triffin Dilemma – the more dollars the US supplied, that is, the more money the US borrowed, the greater was the downward pressure on the dollar. This had already given the dollar a rocky ride in the 1960s and in 1971, its link to gold had to be broken. Thereafter, the unbacked dollar has relied on keeping up demand for the dollar by increasing purely financial demand for the dollar, initially by increasing interest rates and then by inflating asset bubbles in dollar-denominated asset markets, Such bubbles inevitably burst – the dot-com bubble in 2001 and the housing and credit bubbles in 2008, for instance – causing economic and financial harm not only to ordinary working people in the economies affected but also to investors, threatening their confidence in the system.

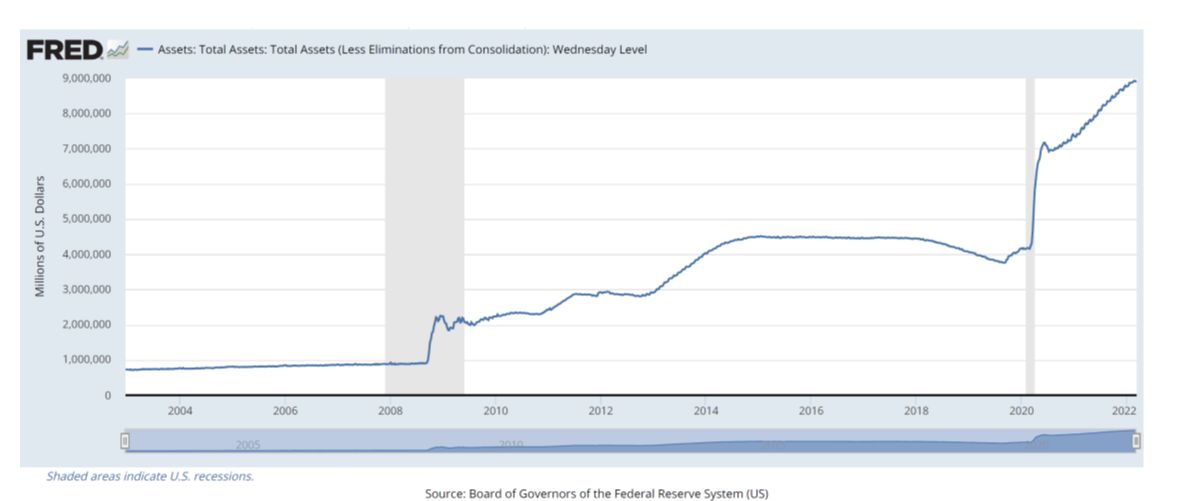

After the 2008 bubble, which has so far been the largest to burst, financial flows into the dollar system declined, particularly from Europe and had to be replaced by the Federal Reserve’s QE programme to support asset markets. This had already inflated the Federal Reserve’s balance sheet from less than a $1 trillion to $2 trillion in 2009, rising gradually to $4 trillion and, as the pandemic interrupted its slow unwinding, to over $9 trillion by 2022. The scale of this support should be seen as a gap between the scale of the flows necessary to support inflated asset markets that constitute the prime attraction of the US dollar and actual flows. While talk of unwinding is necessary to keep confidence in the system, it only functions as a form of con artistry. The market is simply not big enough to buy all these assets if the Federal Reserve actually tried to sell them.

Federal Reserve Balance Sheet, 2004-2022

https://fred.stlouisfed.org/series/WALCL

Even as the dollar system was losing its allure in this fashion, its foundation was further undermined as its legal regime and payments system began tilting in favour of US corporations one-sidedly. A prominent example was the case of the New York court’s judgement in favour of vulture funds that sought the full value of Argentina’s debt even though the established rules of the game entitled them only to a fraction of the debt they bought at a discount. Now, the US government has added the weaponization of the system through sanctions.

Such weaponization not only undermines faith in the system directly among the target countries and similar countries but also indirectly among third, countries, including the US’s western allies, as in the case of sanctions against Iran.

If sanctions have failed in the cases of Cuba, or Venezuela or Iran, they are certainly unlikely to succeed against Russia. They can only harm civilians and make the US that much ore hated in the target countries and their sympathisers. Over the past eight years, Russia has developed considerable resilience against economic sanctions, for instance by turning its agriculture around and becoming one of the world’s major agricultural exporters. Moreover, wary of mounting financial sanctions, Russia, the EU and China are building alternative international payments systems in the form of SPFS, INSTEX and CIPS respectively as well as domestic ones such as China’s Union Pay, India’s RuPay and Brazil’s ELO and they are, further, being coordinated internationally. Finally, it is often forgotten how much the gendarmes of the dollar system, the IMF and the World Bank, have shrunk in terms of their activity and reach as the China-centered international financial system, including not only the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank but also the major banks of China’s financial system, has expanded.

In effect, what the US’s financial sanctions are only accelerating the decline in US power and influence which they are meant to stall.

(This article was originally published in Valdai Club on March 15, 2022)