Liberal opinion is invariably opposed to “nationalism”. It treats “nationalism” as a homogeneous term that…

The Impact of Covid on Remittances in Mesoamerica Jorge Zavaleta

On April 22, 2020, the World Bank reported that 2020 would have the worst decline in remittances in Latin America and the Caribbean in history; about a fifth compared to 2019. Remittances represent a fifth of GDP for El Salvador and Honduras, a tenth for Guatemala and Nicaragua, and less than 5% for Belize, Mexico, Costa Rica, and Panama.

Why were the projections not fulfilled homogeneously for all countries? Remittances to Central America recovered from June. Why so soon?

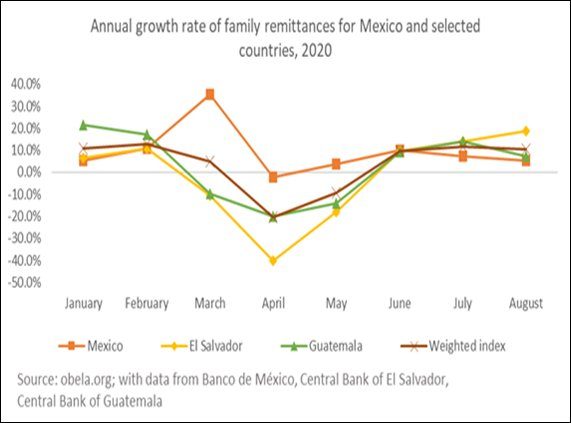

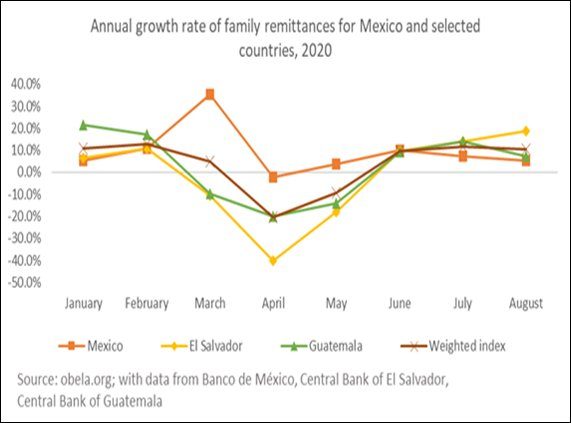

The Governor of California, Newsom, ordered a non-mandatory quarantine in March of year and said State is a Mecca for the displaced: with 10.7 million residing. In April, other States applied social distancing measures. For the countries of origin of both illegal and legal migrants, the effect was a reduction in remittances due to their loss of income. The worst fall in remittances was in April. El Salvador lost 40% of its remittances, Guatemala 20%, and the other Central Americans had the same trend. In Mexico, however, they fell just 2% annually.

Juan José Li Ng points out that remittances from Mexico grew towards the Northwest region of Mexico (Sonora, Chihuahua and Baja California) and decreased in the rest. Exiled Northerners have more extended time in the US, citizenship or permanent residence, and better quality and formal jobs, with support networks and family members. Latinos from Central America and Southeastern Mexico are recent, from the last 15 years. Workers from Central America and Southeastern Mexico do not have the same roots in the United States as those from the Northwest region. The activities in which they work are services, and the end of the confinement allowed them to return to their jobs. South American migrants are proportionally fewer and mostly date from the 1980s, but also the 1970s. That age determines the stability of the flows. On the other hand, the workforce’s quality determines the variability of the funds sent with an apparent inverse relationship between qualification and speed of return to work.

MPI researchers indicated that during the crisis of 2008-2009, Latino visiting workers faced high unemployment. However, they got their jobs back faster than those born in the US.

In March 2020, Latino unemployment was 6% and tripled in the face of the pandemic to 18.9% in April. Women were the most affected. Displaced Latinos were the ethnic group that lost the most jobs, as in the 2008 crisis, and they recovered quickly. In January 2020, the gender gap was 2%, while in April, it increased to 5%. By August, it was back at 2%. According to the MPI, in April, only 40% of working-age Latinas were employed, which meant that Latino families had only one income. Unemployment for this ethnic group fell to 10.9% between June and August with a faster than average recovery (see graph).

The exiled work in industries very vulnerable to the economic cycle. The MPI indicated that foreigners work in accommodation and food services, home services, and construction services. Their work in critical infrastructure sustained their employment in the US. It responds to the relatively low educational level, where they receive low pay, but much higher than what they would have in their countries of origin. Remittances to Central America recovered with the relaxation of confinement in the US.

The catastrophic projections of the World Bank are not fulfilled, fortunately for the Mexican, Central, and South American families who rely on this. Being a migrant and precarious are synonymous and that in the event of any production drop, it is the first unemployed group.

Jorge Zavaleta is a Faculty of Economics, UNAM, member of obela.org .

(We appreciate the comments made by Ms. Daniela Castro Alquicira, researcher at the Political Economy of Development Unit, IIEc, UNAM.)