Donald Trump’s top economic advisor claims the President has weaponised tariffs to ‘persuade’ other nations…

Unravelling India’s Growth Impasse C. P. Chandrasekhar

While it was expected that the Indian economy will experience contraction during the second quarter of 2020, the 23.9 per cent fall in GDP reported by the National Statistical Office came as a surprise to many. For some the surprise lay in the sheer magnitude of the contraction, which was projected by forecasters to be less than 20 per cent. For others, the surprise was that, despite recent controversies about political interference in the reporting of economic statistics, the figure actually provided was as high as it was, and possibly closer to the truth than what the government may have liked.

The 24 per cent GDP contraction figure is remarkable not only because of its sheer magnitude, but also because it is higher than the contraction being reported in other countries where the pandemic was severe. China has reported a positive increase of 3.2 per cent in its second quarter GDP, and UK, a poor performer, recorded contraction of 20.4 per cent, that was lower than India’s.

Yet, the magnitude of the Indian contraction should not come as a surprise. At the end of March 2020, the central government, with little notice, imposed one of the most stringent, nation-wide lockdowns anywhere in the world. Initially slated to last 21 days, the nation-wide lock down was extended and remained pretty stringent all through the second quarter of 2020. Since a lockdown implies that a host of economic activities, except those arbitrarily defined as essential, cannot be undertaken, a contraction in output is inevitable. It is not surprising therefore that economic activities shrank as much as they did, led by construction and trade, hotels, and transport, which were among the most severely hit sectors.

In the official propaganda war, the role of the pandemic-induced lockdowns in influencing the economic contraction has been exploited to advance two kinds of arguments. First, that the economy would experience a V-shaped recovery in the second half of this financial year (2020-21), since the process of lifting the lockdown is underway and is likely to be complete by end of the third quarter of 2020. Second, that policy has had little to do with the contraction, which has been pandemic- and lockdown-led rather than policy influenced.

What the optimism underlying the V-shaped recovery hypothesis obviously misses are the linkages underlying the developments in the second quarter. As the GDP figures show, private consumption and investment have both been badly hit, with private consumption falling by 27 per cent and private investment by 47 per cent in the second quarter of 2020 relative to the corresponding quarter of the previous year. Associated with that fall, other data indicate, has been a significant fall in employment and incomes, which would trigger further reductions in demand either because of a fall in discretionary spending or a decision to postpone purchases. In the circumstances, private investment would not automatically revive, because a quick return to “normal” levels of capacity utilisation is extremely unlikely. Even if the Covid shock were to wane, economic recovery would neither be automatic nor robust.

The reality is that even the probability of a quick fade of the shock is low. In fact, the evidence in India points not just to the likely persistence but even an intensification of the pandemic, before its retreat. This may necessitate a return to lockdowns at the regional or local levels, even if not on a national scale. So even the assumption that what we are going to be left with in the fourth quarter of 2020 is only the aftereffects of the Covid shock may be wrong.

The only way the damaging effects of the pandemic could have been partially countered is by resort to strong government intervention, in the form of a fiscal stimulus. But, as has been underlined by a number of observers, the stimulus package announced in March by the Finance Minister involved largely the repackaging and/or frontloading of expenditure initiatives already announced, and new spending amounted at best to around one per cent of GDP. Given the intensity of the Covid shock that was just a fraction of what was needed to counter its effects. In the event, government expenditure rose only by 16 per cent year-on-year in the second quarter, which was nowhere near adequate to neutralise the decline in private consumption and investment. Remarkably, even after the release of the evidence on the massive contraction in GDP in the second quarter, the government seems reluctant to ramp up its fiscal intervention. So, a prolonged crisis seems unavoidable.

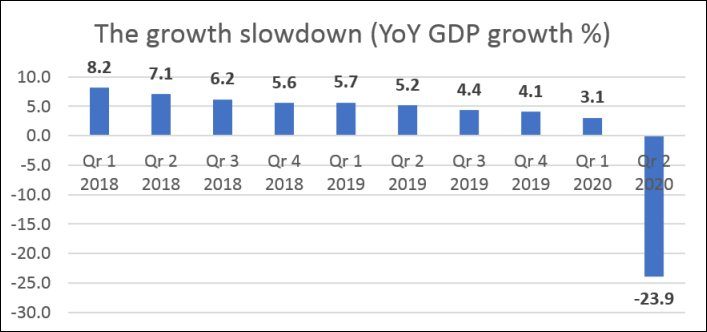

This assessment is, of course, based purely on what the pandemic triggered. But even before the pandemic struck, the India economy, measured even by GDP estimates biased towards inflating growth rates, was slowing dramatically (see Chart). From a high of 8.2 per cent in the first quarter of 2018, the rate of GDP growth (year-on-year) had been falling consistently to touch 3.1 per cent in the first quarter of 2020. That slowdown was driven by a recession in demand, visible across a wide range of sector varying from automobiles to biscuits. There was a strong case for a fiscal stimulus to counteract that slowdown as well. Instead, in September 2019, the Finance Minister decided to offer India’s corporate sector a huge direct tax concession. That temporarily boosted net profits, but did little to revive private investment, since the demand recession had not been addressed. Rather, what the tax cut did was to intensify a fiscal crisis that was brewing because of the loss of tax revenues resulting from the growth slowdown. The Finance Minister made a mistake then, as she did after the onset of the pandemic. The result is bound to be a prolonged and severe recession.

It is in this light that the argument that the second quarter contraction had little to do with policy has to be addressed. Policy did play a role, not only because the choice of an altogether sudden and intensive nation-wide lockdown was a blunder and yielded little that was positive, while devastating the livelihoods and lives of the most vulnerable. The fiscal response to the pandemic was also too tepid to counter its fallout. Policy also did matter because it had, prior to the pandemic, worsened the fiscal crisis facing the Indian State in an attempt to cajole the private sector to play the role that the State should have taken on. In the event, by the time the pandemic came, given the NDA government’s obsession with reporting low fiscal deficit figures and keeping the central government’s borrowing under control, the means to hike expenditures to counter the economic crisis were seen by it as limited.

Meanwhile, one other factor has complicated matters on the ground. The Consumer Price Index for July confirmed ground level perceptions that inflation in India was on the rise. The overall index rose by 6.9 per cent relative to July 2019, which though not alarming in itself, was above the 6 per cent ceiling that a conservative Reserve Bank of India (RBI) had set for its inflation target. This was primarily because, despite good monsoons and increased production, the price index for food items rose by 10 per cent. This was a step up from the corresponding figures of 6.2 and 8.7 per cent for June. Clearly the disruption in supply that the logistical problems that the pandemic had and was creating was taking away some of the benefits that a good monsoon had delivered in terms of agricultural growth. Gross Value Added (GVA) from Agriculture and allied sectors rose 3.4 per cent in the second quarter of 2020, as compared with a 22.8 per cent decline in aggregate GVA across all sectors. Despite this growth prices were on the rise.

That this was some cause for concern for the RBI became clear when its Monetary Policy Committee decided in its August meeting not to further reduce interest rates to drive recovery and ease the economic pain from the Covid pandemic. If in the past a government unthinkingly committed to holding back on the fiscal stimulus looked to the RBI to use monetary measures (however ineffectively) to push for growth, the RBI now seems to be in a mood to hand the baton back to the Finance Ministry. The Reserve Bank of India Governor, in an interview to the Financial Times, while predicting that the inflation rate would moderate in the coming months, also said that “The government will announce more growth-supporting measures.” It is not clear whether that was based on any discussion with the Finance Ministry, though he quickly inserted a note of caution to say: “But whatever fiscal expansion they undertake will be very calibrated and very prudent in its approach.”

In sum, while the Covid-19 pandemic has damaged the economy in India as it has damaged economies elsewhere, the end of a growth episode riding on a credit-bubble, the failure to address the resulting recession, and a tepid State response to the Covid-induced economic shock, has definitely made matters worse. The result is not just the severity of the current crisis that the second quarter GDP figures underline. That crisis would be prolonged, and expectations of a V-shaped recovery amount to mere wishful thinking. In putting the nation in this predicament, policy definitely had a role to play.

(This article was originally published in the Frontline Print edition: September 25, 2020.)