Liberal opinion is invariably opposed to “nationalism”. It treats “nationalism” as a homogeneous term that…

COVID-19 and Patriarchy in the International Year of the Nurse and Midwife Salimah Valiani

In an effort to shed light on the vital but undervalued labour of predominantly female health professionals, the World Health Organisation named 2020 the International Year of the Nurse and Midwife.

It is an irony and sickening reality that 2020 turned out to be the year when nurses and other health workers would be pushed to utter vulnerability in the effort to manage COVID-19. Nurses — the only health professionals who are on hospital floors, 24 hours daily, 7 days weekly, around the world — along with hospital cleaners and community health workers are some of the most important health workers at this time.

Nevertheless, in keeping with the culture of taking these predominantly female workers for granted and undermining their professional knowledge, nurses and others are struggling for protective gear and other supplies crucial to caring for patients.

This is particularly true in Africa, which has the highest nurse to doctor ratio in the world. Compared to other regions, Africa focuses on producing more nurses than doctors. According to some of the latest data, the nurse to doctor ratio in Sub-Saharan Africa is 5.2 nurses to 1 doctor, versus 2.1 to 1 in Europe, 1.8 to 1 in Southeast Asia, and 2.5 to 1 in the Americas (https://www.nejm.org/doi/full/10.1056/NEJMra1111610).

Despite this focus, African countries have low ratios of nurses and midwives to every 10,000 people, whether they are medium or low-income countries. Burkina Faso, Malawi and Nigeria have as low as 9, 4 and 12 nurses and midwives per 10,000 population respectively. Ghana, South Africa and Botswana have 42, 49 and 54 per 10,000 population.

These compare with Brazil’s 101 nurses and midwives per 10,000 population, Cuba’s 75, Russia’s 85, the USA’s 145 and Norway’s 182 nurses per 10,000 population.

For essential maternal and child health services alone, the World Health Organization recommends a minimum of 23 doctors, nurses and midwives per 10,000 population. Many more are required for daily health system functioning, including being prepared for epidemics. As seen in the mayhem and rising COVID-19 cases in Nelson Mandela Bay and other parts of South Africa today, to try and iron out labour relations issues and fill longstanding nurse shortages amidst a pandemic is much too late.

Nurses per 10,000 population, latest data,

(WHO Global Health Observatory)

| Algeria (2018) | 15 |

| Angola (2018) | 4 |

| Botswana (2018) | 54 |

| Burkina Faso (2017) | 9 |

| Egypt (2018) | 19 |

| Gabon (2017) | 29 |

| Ghana (2018) | 42 |

| Kenya (2018) | 11 |

| Malawi (2018) | 4 |

Nigeria (2019) |

12 |

| South Africa (2018) | 49 |

| Uganda (2018) | 12 |

So why are there so few nurses in Africa, the continent that registers one quarter of the world’s deaths due to illness? There are two main reasons: inadequate healthcare spending by governments in Africa and patriarchy.

Several African governments spend more on debt repayment than public healthcare. Ghana spends 5 times more on interest payments than on healthcare. Nigeria and Kenya respectively spend 3 and 2 times their healthcare budgets on debt repayments.

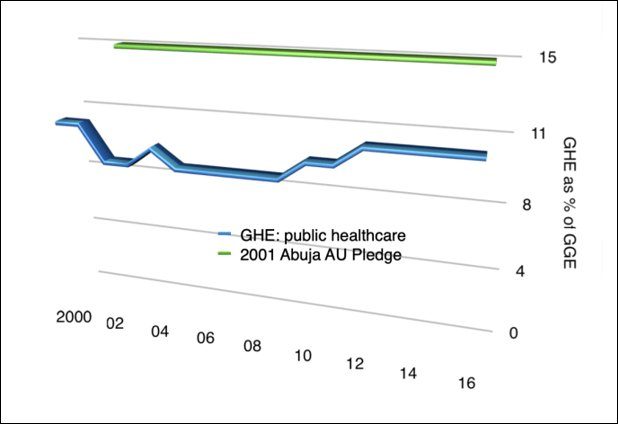

In South Africa, government health expenditure as a share of general government expenditure has hovered between 8 and 10 per cent since 2000 (see figure). This is despite the fact that 84 per cent of the population is too impoverished to use private healthcare and depends on the public healthcare system.

Government Health Expenditure (GHE) as

Percentage of General Government Expenditure (GGE), 2000-2016

(Source: World Health Organization Global Health Expenditure Database, 2019)

Such spending choices have persisted even though African states committed to allocating 15 per cent of government expenditure to healthcare in the 2001 Abuja Declaration on HIV/AIDs, Tuberculosis and other Related Infectious Diseases.

Hand in hand with this is the choice by African states to rely on value added and other consumption taxes detrimental to the majority to increase public revenue rather than working to collect adequate taxes from corporations and wealthy individuals. In South Africa this has expressed itself in the current pandemic in the embarrassment of the state asking for corporate donations for basics like personal protective equipment, creating new COVID-19 hospitals beds, and buying space for quarantining ill individuals.

The fallback is to lay the burden of social inequality, as it takes shape in worsening population health, on women: the providers of both unpaid and paid care. This is not only the case in Africa, but also elsewhere. In most health systems, even where paid relatively well, nurses are overworked and face trying working conditions. As I argue in my book, Rethinking Unequal Exchange – The global integration of nursing labour markets (https://utorontopress.com/us/rethinking-unequal-exchange-4) this is largely what has led to the global integration of nursing labour markets, as nurses leave home in search of better working conditions.

Rather than recognising and resolving the systemic issues leading to under-resourced healthcare, particularly in African countries, nurses are blamed for ‘poor attitudes’, inadequate service provision, and even face workplace violence (https://www.academia.edu/41929022/Public_Health_Care_Spending_in_South_Africa_and_the_Impact_on_Nurses_25_years_of_democracy).

Given these patriarchal tendencies in society at large, the experiences of nurses in the International Year of the Nurse and Midwife are not surprising.

South of Gauteng, nurses of a public clinic in Sebokeng were still working without protective gear in May and were left to find their own means of transport during lockdown levels 5 and 4. A nurse reported that two of her colleagues were shot by police while waiting for transport outside the clinic gate.

Also in May, nurses of a tuberculosis hospital in Eastern Cape were protesting the conversion of their workplace into a COVID-19 hospital, stressing concern for the needs of TB patients. Hospital and clinic nurses in Nelson Mandela Bay contracted COVID-19 because managers were withholding protective gear they claimed was for when the virus was more widespread.

A hospital nurse in Dar-es-Salaam interviewed by Al Jazeera in April used the term ‘collateral damage’ for the way frontline workers felt in face of government neglect. She outlined the neglect as ranging from not curbing religious and other gatherings known to be key in spreading the coronavirus, to not providing protective gear and COVID-19 training to public health workers (https://www.academia.edu/41929022/Public_Health_Care_Spending_in_South_Africa_and_the_Impact_on_Nurses_25_years_of_democracy).

In Liberia, collective expertise and efforts dating back to Ebola times have been revived to confront the coronavirus pandemic, but frontline workers underscore the challenges given that healthcare infrastructure has not been strengthened since Ebola.

Since the end of March, nurse and other health worker unions in Togo and Cote d’Ivoire have been making explicit to states the medical equipment and other health system needs to manage the pandemic. Among the first 34 lives taken by COVID-19 in Togo, 4 were those of health workers.

In the DRC’s South Kivu province, 6000 nurses began a strike mid-May to demand unpaid wages and clarity around COVID-19 risk pay. As Byamungu Mushagulusa, one of the striking nurses said in an interview with TV5 Monde, ‘the nurse is the backbone of the health system but is unfortunately neglected by the state and the entire hierarchy’ (https://information.tv5monde.com/video/coronavirus-en-rdc-6000-infirmiers-en-greve-dans-l-est-du-pays).

Community health workers have been key in carrying out coronavirus screening in communities in South Africa, but it is unclear whether they are being remunerated at the national minimum wage, a promise first made in Budget 2019 and remade in Budget 2020. Similarly, community health workers typically work on temporary contracts for consecutive years rather than being made permanent employees with the accompanying benefits.

Ghana offers some hope in the continent. In April, with the onset of COVID-19, President Nana Akufo-Addo announced the largest health infrastructure investment in Ghana’s history. This year, Ghana will begin building 88 hospitals in the districts still lacking them, 6 new regional hospitals, and 3 infectious disease control centres (https://citinewsroom.com/2020/04/covid-19-government-to-begin-construction-of-88-district-hospitals-this-year-nana-addo/amp/).

For too long, Africans have blamed international financial institutions, structural adjustment and globalisation for poor public services. African governments, however, particularly now, have the power to refuse additional loans and conditions, arrange loan repayments or even default in the best interest of the majority, as Argentina did in 2001.

If Covid-19 teaches anything, it is the need to democratically define, erect and defend universal public healthcare, including acknowledging and valuing the leading role of nurses and other female health workers.

(Salimah Valiani is a researcher with a background in world historical political economy.)

(This Article was originally published in Daraja Press on June 7, 2020.)