Corporate-dominated food systems are responsible for widespread but still spreading malnutrition and ill health. Poor…

Claims versus Reality: Who Benefits from Government Funded Health Insurance? Ankur Verma

Health insurance has been the focus of the health policy of the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP)-led NDA government. While health insurance schemes had been introduced by the previous Congress-led United Progressive Alliance government, as well as by several state governments, these became a centre piece of the national health policy during the current regime.

In the budget speech of 2016-17, the Finance Minister had announced that “the Government will launch a new health protection scheme which will provide health cover up to Rs. One lakh per family. For senior citizens of age 60 years and above belonging to this category, an additional top-up package up to 30,000 will be provided.”

This emphasis on health insurance as primary means of providing public support for health care intensified further in years to come as PM Jan Arogya Yojana (PM-JAY) under the Ayushman Bharat programme was presented as the centre piece of the budget in 2018.

In 2018, the Finance Minister declared that “we will launch a flagship National Health Protection Scheme to cover over 10 crore poor and vulnerable families (approximately 50 crore beneficiaries) providing coverage upto 5 lakh rupees per family per year for secondary and tertiary care hospitalization. This will be the world’s largest government funded health care programme. Adequate funds will be provided for smooth implementation of this programme.”

This increased reliance on health insurance marked a shift in approach towards greater reliance on private health care providers rather than on the public health system.

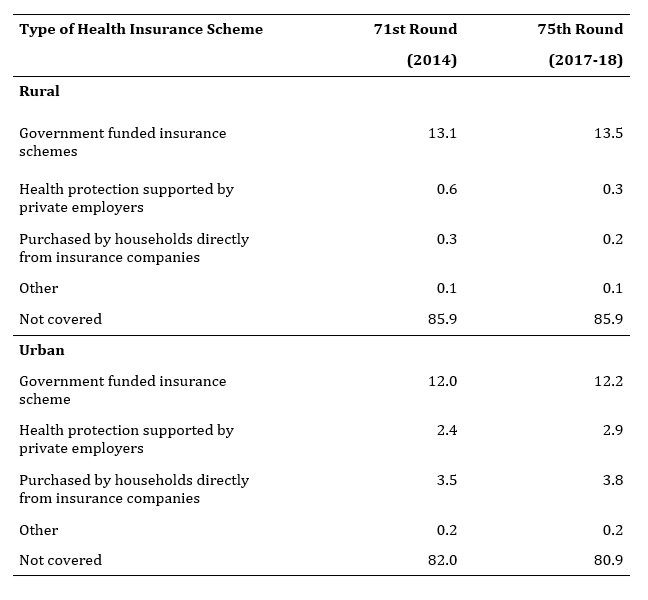

It is in this context that data on health insurance collected as part of the 75th round of National Sample Survey on health become particularly interesting. The survey report shows that, for all the noise made on health insurance, the coverage of health insurance did not increase in India between 2014 and 2018. According to these data, in 2017-18, 85.9 per cent of rural population and 82 per cent of the urban population was not covered by any kind of health insurance. This proportion has remained unchanged for rural areas since 2014, when the previous NSS survey on health was conducted. The coverage of health insurance schemes increased by only 1.1 percentage points in urban areas during this period.

It may be noted that the bulk of those who are covered by health insurance get that access through government funded schemes. Private health insurance provides coverage to a negligible proportion of the population (Table 1). In rural India, only 0.2 per cent of the population was covered through privately purchased health insurance policies while another 0.3 per cent population was covered by health insurance supported by private-sector employers. In urban areas, only 3.8 per cent of the population was covered by privately purchased health insurance policies and only 2.9 per cent through health insurance cover provided by private-sector employers.

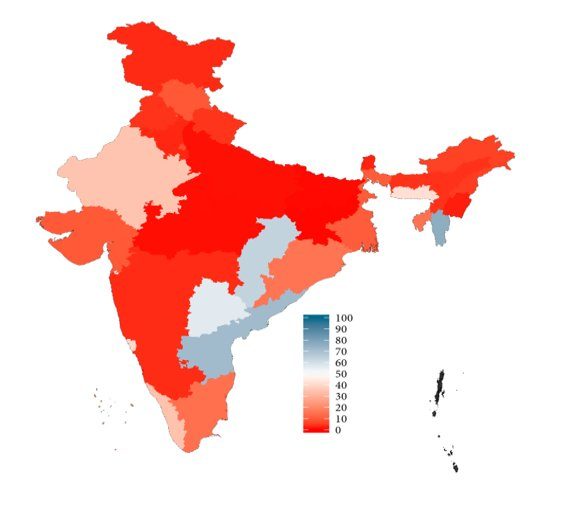

There is a notable variation across States in respect of the proportion of population that is covered under government-funded health insurance (Figure 1). While the coverage is abysmally low in most States, Andhra Pradesh, Telangana, Chhattisgarh and Mizoram stand out for very high coverage. Coverage of health insurance is also substantial in Kerala, Meghalaya and Rajasthan. In most of these States (for example, Andhra Pradesh, Telangana, Kerala and Chhattisgarh), high coverage of population in health insurance programmes is a result of State-level health insurance schemes which are universal or near-universal in terms of eligibility.

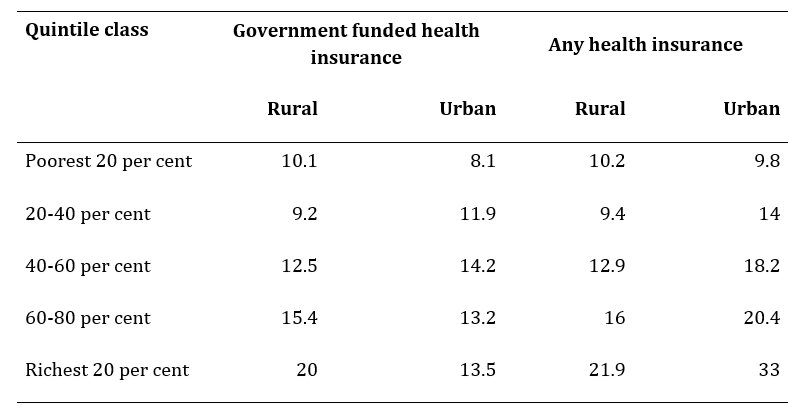

Another important point that emerges from the survey data is that government-sponsored health insurance, including schemes that are meant for the poor, disproportionately covers relatively rich households (Table 2). If we look at the poorest (bottom 20 per cent in terms of household expenditure) rural households, only about 10 per cent of people in such were covered by health insurance. Almost all of this was government-sponsored health insurance.

On the other hand, among the richest (top 20 per cent in terms of household expenditure) in rural areas, the coverage of health insurance was 22 per cent. Of these, 20 per cent was government-sponsored. In urban areas, in the poorest households, government-sponsored health insurance covered about 8 per cent of the population.

In the case of richest urban households, government-sponsored health insurance covered 13.5 per cent of the population. Another 20 per cent population among these urban rich households was covered through insurance provided by private employers or directly purchased health insurance.

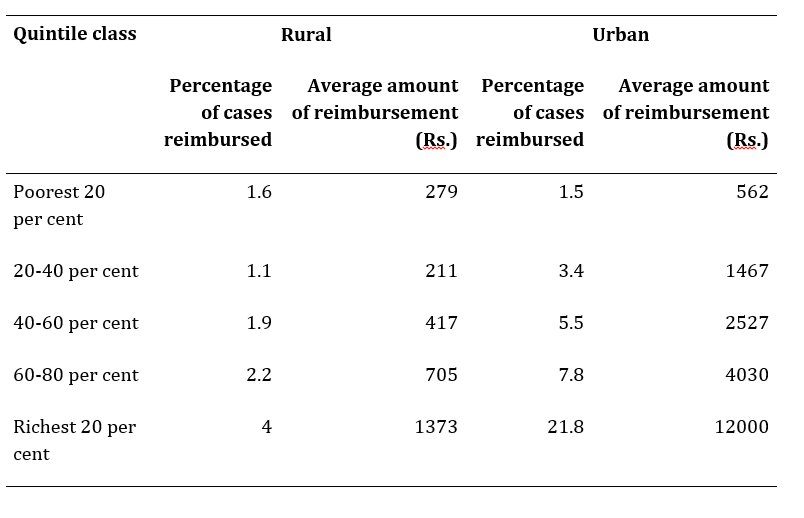

With higher coverage of government-sponsored insurance, employer-sponsored insurance and privately-obtained insurance, relatively richer households get much higher proportion of their hospitalisation expenses covered through these different sources than the relatively poor households do (Table 3). For example, in rural areas, poorest households got reimbursement of expenses only for about 1.6 per cent of the cases of hospitalisation while this proportion was 4 per cent of the richest households.

When rural households did get some reimbursement, it covered only 4 per cent of total hospitalisation expenses of the poorest while 22 per cent of hospitalisation expenses of the richest households was covered. Similarly, in urban areas, 1.5 per cent cases of hospitalisation of poorest households were covered while in case of richest households 22 per cent cases of hospitalisation were covered.

For urban poor, reimbursements covered only 4 per cent of expenses while the corresponding proportion for urban rich was 27 per cent. In absolute terms also, the inequality in benefits received was extremely stark: while the rural poor received an average of only Rs. 279 in reimbursements for hospitalisation, urban rich received an average reimbursement of Rs. 12000 per case of hospitalisation.

In recent years, an increasing share of the government’s health budget has gone for funding health insurance schemes. While these were originally planned to be run by the government, or government supported independent institutions, in the recent years, private companies have been increasingly roped in to provide health insurance under the government funded schemes.

Such a model of providing health care has been found to be fraught with many kinds of problems world over. First, there are serious moral hazard problems in the insurance-based model of health care, resulting in both governments and people having to incur much higher expenditure on health care than in case of health care provided through public institutions. In states that have large-scale health insurance schemes, the fiscal burden of these schemes is quite substantial. With strong fiscal austerity targets imposed under the neoliberal regime, this has resulted in diversion of funds from other areas of public health.

Second, insurance-based health care prioritises in-patient, tertiary care rather than dealing with health issues through primary and secondary health care. A stronger system of primary and secondary public health care would hugely reduce the burden of tertiary care.

Third, given the huge gaps in availability of medical facilities in many States having health insurance cover does not ensure availability of health care. With an increasing shift of public resources towards health insurance, public health facilities are reeling under a severe fund crunch and are unable to provide primary and secondary health care. On the other hand, private health facilities grow only in areas where people have paying capacity for health care.

The data that have become available from the recent survey show that health insurance coverage in India has not expanded at all between 2014 and 2018. It is only in a few states, where near universal eligibility for health insurance coverage has been introduced through state-level schemes, that the coverage of health insurance is substantial. The data also show that the benefits of health insurance, both in terms of coverage and in terms of reimbursements, disproportionately accrue to relatively richer households while the poor are left high and dry.

Table 1: Percentage of persons covered under different types

of health insurance schemes by sector, 2014 and 2018

Figure 1: Proportion of population covered by government funded

health insurance, by State, 2017-18 (per cent)

Table 2: Proportion of population covered in government funded

or any other health insurance, by quintile class of household expenditure, 2018

Table 3: Percentage of hospitalisation cases in which some reimbursement was received and average amount of reimbursement per case of hospitalisation, by quintile class of household expenditure, 2018

* Ankur Verma is a Research Scholar, Jawharlal Nehru University, New Delhi

* Ankur Verma is a Research Scholar, Jawharlal Nehru University, New Delhi

(Email: ankurverma.jnu@gmail.com)