Donald Trump’s top economic advisor claims the President has weaponised tariffs to ‘persuade’ other nations…

Reviving India’s household savings and investments should be the budget’s top concern Jayati Ghosh

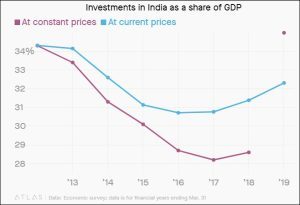

Falling investment rates have cast a shadow on claims of a buoyant and dynamic India made by successive governments. Before it came to power in 2014, the ruling Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) had made it a political issue. Since then, it has been less than successful in restoring investments to levels seen in the first decade of the century.

The government now argues that investment rates have finally begun to rise. While this may be true, current rates are still low compared to financial year 2012, or even earlier years. In constant price terms, real investment as a share of GDP fell even more sharply and barely seems to be recovering.

Investments in India as a share of GDP

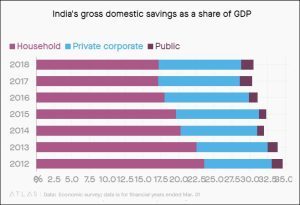

Households not saving enough

The decline in investment rates is tied to another concern: falling domestic savings rates. This has been led by lower household savings, which fell by 6.4 percentage points in a short span of seven years.

India’s gross domestic savings as a share of GDP

This would come as no surprise given the steep slump in India’s construction sector, both in terms of output and employment, in the past few years. The downturn reflects the damage done to the livelihood and income of a majority of the population, leading to muted consumption and demand.

The claims of rapid growth routinely trotted out by government spokespersons notwithstanding, there are underlying problems to be sorted out to ensure that investment revives.

One of these is the mess in financial intermediation that has led to a combination of high bad loan ratios for banks and a collapse in non-bank lending to smaller enterprises, especially after the shock delivered by the non-banking financial company IL&FS.

Things may get worse before they get better. Tight and rationed credit will remain a problem for those willing to borrow and invest, while those who get loans easily may not find it attractive to borrow for productive investment if the market is not growing.

Is there a solution?

So, the big question is how exactly will the budget to be presented by Nirmala Sitharaman address the issue of investment revival?

The latest economic survey does not provide much guidance on this, as its main focus is on the possible policy “nudges” that are provided by insights from behavioural economics.

Falling savings rates reflect the real economic conditions of savers, not their inclinations. Declining investment rates are more about the behaviour of relatively impersonal economic forces rather than persons whose psychology can be manipulated to produce the desired result.

So, as far as addressing the need to generate a revival of investment and savings is concerned, behavioural economics on its own is not going to cut it.

Those looking at what the budget provides for economic growth normally obsess over big corporate investors. Yet, the real story of growth and investment in the Indian economy is mainly to be found in the hundreds of millions of households and small enterprises that constitute the bulk of employment in the country. So that is the issue that should be highlighted when the budget is presented.

(This article was originally published in The Quartz India on July 5, 2019)