The 2020s is turning out to be a decade of great unravelling of the global…

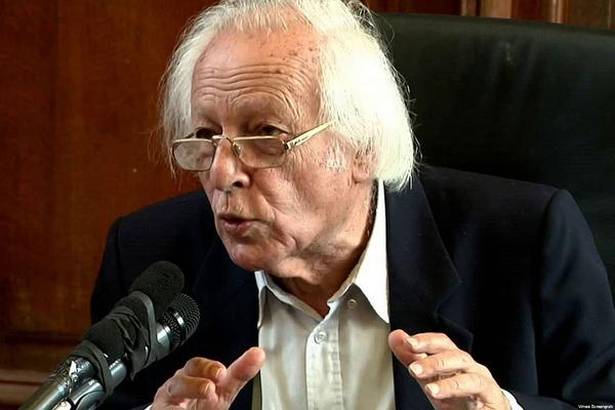

In Memoriam: Samir Amin

IDEAs network mourns the loss of the celebrated Marxist thinker Samir Amin, who was also a Member of our Advisory Board. Samir Amin’s razor-sharp intellect, penetrating analysis, strong anti-imperialism and conviction in the importance of third world solidarity as well as his deep and continuous commitment to progressive causes around the world, will continue to remain an inspiration for us.

We publish below an obituary by Prabhat Patnaik, Jayati Ghosh and C.P. Chandrasekhar.

Samir Amin (1931-2018)

A Marxist from the Third World

C. P. Chandrasekhar

1 September 2018

Samir Amin, a leading social thinker, campaigner and activist of and for the South is no more. Progressive forces, not just in Africa where he was born, and lived and worked for most of his life, but across the underdeveloped world will miss the presence of a person who was never tired of speaking truth to the apologists and functionaries of imperialism. Especially because, besides his energy, charm and deep commitment, what singled out Amin was his ability to connect with intellectuals, activists and movements across the developing world—across Asia and Latin America, and not just in Africa. That network to him was not just one of solidarity among those faced with similar problems, but a movement that needed to be built to confront and transcend a global structure that was responsible for underdevelopment, deprivation and poverty.

Born in 1931 in Cairo, Amin followed a trajectory characteristic of many radical intellectuals from ex-colonial countries, studying and working both in Africa and its coloniser, France. He was in his early teens when the Second World War ended, Britain had ceded power to the US as global hegemon, and the process of decolonisation that had begun before the war had gathered momentum. These were the years when anti-colonial sentiments were strong, independent national governments came to power, ‘delinking’ through import substitution was underway in many less developed countries, a ‘socialist’ Soviet Union was an important global influence, and planning was being experimented with even in predominantly market-driven economies. Like many other radical thinkers, Amin recognised the promise in these trends. So, though a Marxist by persuasion, he joined the many radical intellectuals in the Third World who chose to work with their newly independent governments in the hope that they would follow a path which, while aiming to accelerate productivity and income growth, would distribute the benefits of that growth in ways that would address the underemployment and deprivation that afflicted the majority. He worked with the planning board in Egypt during 1957-60, before he was forced into exile, with the Ministry of Planning in Mali during 1960-63 and then as director of the African Institute for Economic Development and Planning in Dakar for a decade.

These occupational choices reflected the belief that, given an appropriately enlightened government and adequate social sanction, trajectories of development that advanced social good could be engineered even within non-socialist economies. But as happened across the Third World, import substitution and planning failed to deliver in Africa. After flirting with egalitarian alternatives, governments compromised with vested interests of various kinds and settled for a path of state-facilitated capitalist development that delivered some growth but transferred much of its benefits to an elite. In time, growth too proved unsustainable.

Samir Amin was not one to uncritically accept such an outcome, and was among the communists and radicals who were forced into exile from Egypt by Abdel Nasser. That took him into a career in which he spent much time elsewhere in Africa, leading an intellectual current seeking out alternatives for freedom from oppression and deprivation for the underprivileged. Though his emancipatory project was focused on Africa and his locational shifts within Africa made him a pan-Africanist in physical and conceptual terms, he saw himself as one among those shaping a movement for emancipation from oppression and egalitarian development across the Third World. His personal experience, however, did not lead to the conclusion that the problem in underdeveloped countries was just one of exploitative elites and the governments that represented them. He attributed the failure of those governments to their inability to confront the global structures reproducing inequality and deprivation that had been shaped through capitalist history and under colonialism. In his view, imperialism, and the monopolisation of resources, finance and knowledge by the classes that dominated in the developed nations, had condemned the ‘bourgeois’ nationalist project to failure. An alternative was required. The emancipation of the Third World depended on its delinking from imperialism, and finally on the overthrow of the latter.

These were not just emotional words and baseless beliefs. Over his career Samir Amin creatively applied the Marxist method to understand what Marx had inadequately investigated in his incomplete life’s work—the mechanisms that ensured that development in the metropolitan centres of capitalism had as its counterpart the underdevelopment of the periphery, making generalised catch-up or convergence under capitalism an impossibility. To unravel those mechanisms he chose to extract the theory of value from a model of an abstract capitalist economy, and apply it to the concrete conditions of accumulation on a world scale. That led to the development-underdevelopment dichotomy. The Law of Worldwide Value, as one of his books was titled, was one which took account of the phenomenon of unequal exchange, deriving in the final analysis from the fact that a unit of (otherwise similar) labour power was valued less in the periphery then in the core advanced countries. That is, surplus extracted from Third World workers emerged not only because they contributed more to the value of the product they produced than the value of labour power itself, but because similar labour was valued less in the periphery than in the core. When that was taken into account, an explanation of why capitalist accumulation leads to development at the core and underdevelopment in the periphery emerges. Even those of Leftist persuasion who felt this formulation was not nuanced enough, had to accept that this was an idea that was potent, given historical experience and persisting international inequality. The burden of Amin’s argument was that historically evolved exploitative structures continue to reproduce this anomaly. Unless poor countries detached themselves from those structures, or the global system in which those structures were embedded was transcended, the development project within an integrated world economy was doomed to failure.

This conceptual understanding of Amin’s translated in practice into an appreciation of the radical strand in nationalist struggles and the non-aligned movement, which he wanted to retrieve. Hence the celebration of the ‘Bandung spirit’, or the spirit that the Bandung Conference of African and Asian nations held in 1955 in Indonesia was imbued with. In a concept note for a conference to celebrate 60 years of Bandung in 2015 Amin wrote: “The Conference of Bandung declared the will of the Asian and African nations to reconquer their sovereignty and complete their independence through a process of authentic independent consistent development to the benefit of all labouring classes.” He saw Bandung as “the first international meeting of ‘non-European’ (so called ‘coloured’) nations whose rights had been denied by historical colonialism/imperialism of Europe, the US and Japan.” He also saw in the Bandung spirit a willingness of people across the Third World to come together in the struggle against imperialist domination. His political life was geared to strengthening that sentiment and institutionalising it in various ways.

Amin saw the continuation of the radical nationalist project as a process that would lead to emancipation through a 21st-century version of the socialist transformation. This perception marked his Marxist approach as uniquely Third Worldist, and different from one adopted by many western Marxists. Amin was an anti-imperialist nationalist and a socialist. Even conceptually, his understanding as an African and a citizen of the Third World dominated that stemming from his exposure to France and the rest of the developed world.

(This article was originally published in the Frontline Print edition: September 14, 2018)

Remembering Samir Amin, Who Dedicated Himself to Overcoming Capitalism

Jayati Ghosh

22 August 2018

Samir Amin (September 3, 1931-August 12, 2018) was a visionary: someone with his own very strong ideas of what the future should be like, and consumed by the need to mobilise people to work for bringing about such a future. The desirable (though not inevitable) future for him was that of socialism, which required the defeat of imperialism and the overcoming of capitalism. The intense enthusiasm with which he sought to pursue that vision, to the very end of his immensely productive life, was at once obsessive, beguiling and infectious.

Amin was born in 1931 of Egyptian and French parentage, and was brought up in Port Said in Egypt, but his subsequent education and his own inclinations made him much more cosmopolitan, truly a citizen of the world – or rather of the Third World. Indeed, he self-identified as an African scholar of political economy and was hugely devoted to encouraging and developing rigorous intellectual life in that continent.

His early professional experiences were clearly crucial in developing that orientation. Already in secondary school he considered himself a communist, and he was a member of the French Communist Party as a student in Paris in the 1950s. His PhD thesis in Paris in 1957 was on the origins of underdevelopment, presenting the germ of ideas that subsequently were elaborated in his magnum opus Accumulation on a World Scale that was first published in 1970. He returned to Cairo to work as a research officer in the Office of Economic Management of the Egyptian government, but the anti-communism that marked the Nasser regime at that time drove him to exile, followed by a stint in Mali working for that country’s government.

Thereafter, he was mostly based in Dakar, Senegal – first in the UN’s Institut Africain de Développement Economique et de Planification, of which he became the director in 1970, and then as the director of the Forum du Tiers Monde (Third World Forum) that he set up in 1980. He was instrumental in setting up the Council for the Development of Social Science Research in Africa (Codesria), which has become the main vehicle of social science research and analysis in the continent and currently has more than 4,000 active members.

Such activity reflected his pan-Africanism, which was an essential and abiding part of his personality and his intellectual leanings. But he did not see this as a simplistic celebration of one homogenised “African culture”, which in any case he recognised as a false construct. In a moving tribute, the young Tanzanian social scientist Natasha Issa Shivji has pointed out that Amin argued for pan-Africanism as “a project of the oppressed of Africa against imperialism and its compradors… as a political project from below, as a class project in defence of the peasantry and the working people and an anti-imperialist project birthed from the nationalist movements.”

Samir Amin

Accumulation on a World Scale

Amin had a sharp intellect and little patience for academic dissemblers, whom he saw through easily. He had an appropriately cynical attitude to mainstream economics, which he saw as little more than a discourse “to legitimise the unrestricted predations of capital,” and dismissed the claims of economics to being a pure science as little more than “magic and witchcraft”. His own analytical framework was that of Marxian political economy, of which he developed his own specifically anti-imperialist variant that presumed the existence of unequal exchange between North and South, that systematically impoverishes the South in various ways.

So for Amin, capitalism, which was always a global system, was critically dependent on the polarisation between centre and periphery, and the logic of capital accumulation was such that the periphery could never catch up with the centre. Thus Amin became one of the most celebrated proponents of “dependency theory”, which he developed in several books such as Accumulation on a World Scale; Eurocentrism; and Imperialism and Unequal Development. According to him (as elaborated in his book Capitalism in the Age of Globalization, London: Zed Books, 1997), the fundamentally unequal relationship between centre and periphery is characterised by the five monopolies which reproduce global capitalism.

These are: the monopoly of technology generated by the military expenditures of the imperialist centres; the monopoly of access to natural resources; the monopoly over finance; the monopoly over international communication and the media and the monopoly over the means of mass destruction.

The way to combat this is through “delinking” – an idea he developed in a book of the same title in 1990. He did not view this as a simple reversion to autarky in trade or isolationism. Rather, he saw “delinking” as “the refusal to subject the national development strategy to the imperatives of worldwide expansion”, based on rejecting the dictates of the centre with regard to economic policies that ultimately benefit the centre rather than the periphery in which they are deployed. The requirement of delinking extended from specific policies to institutional structures that formed the very basis of social and political existence in the countries of the periphery. Thus, Amin was very critical of the models of development and of the institutional structures of nation-states in developing countries that slavishly imitated the West, which he felt enabled colonialism to easily transmogrify into neo-colonialism.

Delinking requires politically bold governments with sufficient mass support, which would have the confidence to reject strategies based on static comparative advantage and break the stranglehold of comprador interests over state policy. In addition to domestic political economy forces in support of this, it also requires much greater South-South co-operation, which should be based on economic relations that avoided reproducing relations of exploitation that characterised interactions between the capitalist core and periphery. It also requires strengthening the co-operation between progressive forces across North and South.

An offshoot of this is the urge to a multipolar world – so Amin very much welcomed the emergence of new powers and the waning of US global power. He was optimistic enough to believe that as the world system fragments and comes apart, there would be greater possibilities for his much-anticipated revolt of the working classes of the North against capitalism itself.

However, he was also shrewd enough to realise that multipolarity does not necessarily represent a decline in imperialist tendencies or in traditional centre-periphery relations of hierarchy and domination. In a fairly complex but nonetheless sweeping analysis (The Law of Worldwide Value, New York: Monthly Review Press, 2010), he identified six global classes of significance: (1) the imperialist bourgeoisie at the centre or core, to which accrues most of the global economic surplus value; (2) the proletariat at the centre, which earlier benefited from being a labour aristocracy that could enjoy real wage increases broadly in line with labour productivity, but which was now more threatened and experiencing falling wage shares and more insecure employment conditions; (3) the dependent bourgeoisie of the periphery, which exists in what he saw as an essentially comprador relationship with multinational capital based in the core; (4) the proletariat of the periphery, which is subject to super-exploitation, and for whom there is a huge disconnect between wages and actual productivity because of unequal exchange; (5) the peasantries of the periphery, who also suffer similarly, and are oppressed in dual manner by pre-capitalist and capitalist forms of production; and (6) the oppressive classes of the non-capitalist modes (such as traditional oligarchs, warlords and power brokers).

This obviously creates an extremely complex set of struggles and alliances. And it means that even relations between economies in the peripheries would not always necessarily display the characteristics of working class and peasant solidarity that he hoped for.

Indeed, the possibilities of such complexity were increasingly recognised by Amir when it came to the role of religious fundamentalism as a supposedly anti-imperialist expression. While anti-imperialism was his deepest and most abiding characteristic, he was also ruthless in his critique of religious fundamentalist movements. He was a vehement opponent of the Muslim Brotherhood in Egypt, criticising them sharply not only for their revanchist religious dogma with its socially regressive implications, but also because he believed that in economic terms they would apply the same neoliberal policies that the centre typically wanted to impose on peripheral countries. He even supported the military coup in Egypt – to the dismay of many of his friends and fellow-travellers – because of his deep opposition to both the politics and economics represented by such groups, and he felt strongly that they could never be part of a truly emancipatory movement.

These are strong views, and Amir always expressed them forcefully. But he was also a man of great personal charm, able to connect to people across the world of different backgrounds and ages, with little recognition of conventional hierarchies of age, achievement or experience. And his tenacity and untiring commitment were unbelievable. Even a few weeks before his death, I and many others among his friends and comrades across the world received emails from him reiterating the need for a new International and insisting on enlisting us for this cause, with demands for clear commitments with regard to time and output. He brought his formidable intellect and persuasive powers to this with so much energy that we were shamed into compliance, promising to take this forward. So we cannot even begin to say farewell, Amir, until we have done at least some of what we promised you.

SAMIR AMIN (1931-2018)

Prabhat Patnaik

14 August 2018

Samir Amin, the renowned Marxist thinker and economist, passed away on August 13 in Paris. Born in Cairo on September 3, 1931, to an Egyptian father and a French mother, he had his initial education in Egypt before moving to Paris where he obtained his doctorate in Political Economy. Drawn to the cause of socialism from his student days he soon became a member of the Egyptian Communist Party. Between 1957 and 1960 he worked at the Institute for Economic Management in Cairo, before Nasser’s growing repression of the Communists drove him out of Egypt. He eventually settled down in Dakar, Senegal, first as the Director of the UN African Institute of Economic Development and Planning and later as the Director of the African Office of the Third World Forum.

Two characteristics set Samir Amin apart from most other Marxist intellectuals of his time. One was his total and absolute commitment to praxis for the cause of socialism. He was not a mere arm-chair theorist who used Marxist tools to analyze the contemporary reality as a form of detached intellectual activity. He was on the contrary a passionately-committed activist, for whom intellectual activity was quintessentially an aid to praxis. He was forever trying to organize fellow-activists for making effective interventions to bring about change, and was closely associated with real movements, both the Communist movement in Senegal and also several NGO movements, all of whom looked up to him for help and guidance.

The second characteristic was the centrality he accorded to imperialism in his Marxist analysis, which is so different from what one normally finds both among first world Marxists (with rare exceptions like the Monthly Review group) and also among many third world Marxists who, oddly, see in neo-liberal globalization a withering away of imperialism. Amin in contrast not only saw imperialism as central to capitalism, but placed it firmly within the framework of the Labour Theory of Value through his theory of unequal exchange for which he is justly celebrated.

The fact that metropolitan capitalism’s annexation of the third world had given rise to a process of unequal exchange had been widely recognized. The question however related to the “norm” with respect to which exchange could be described as unequal. Many would, and did, accept the proposition, which followed clearly from Michal Kalecki’s analysis, that a rise in the “degree of monopoly” within metropolitan capitalism gave rise to a greater squeeze on third world primary commodity producers; but this only made some particular historical date (from which the rise in the degree of monopoly is measured) the norm, or the origin, in relation to which we could locate unequal exchange.

Amin, and other theorists of unequal exchange like Emmanuel, saw the point of departure not as a date but as a conceptual position. For Amin unequal exchange was manifest in the fact that the value added over a specific period of time by a unit of simple labour in the periphery was counted as less than the value added over a similar period by a unit of simple labour in the metropolis, which was also associated with the fact that the value of labour-power in the periphery was less than that in the metropolis.

It is clear that for Amin it was not unequal exchange per se that was conceptually central but the fact of super-exploitation. Even if, for instance, the commodities produced by the periphery exchanged against those produced by the metropolis at their respective amounts of total (i.e. direct and indirect) labour-time embodied, as long as the value of labour-power in the former remained below that in the latter because of the former’s massive labour reserves, this super-exploitation will continue; the only difference would be that larger profits would accrue to those who sell the commodities of the periphery (which could well be the MNCs from the metropolis). Central to Amin’s perception of imperialism and of unequal exchange therefore is this fact of super exploitation of the workers of the periphery.

To critics, among whom was Charles Bettelheim, who argued that the value of labor-power relative to labour productivity was lower in the metropolis than in the periphery, so that there was no question of any super-exploitation of the workers in the periphery, the obvious answer was that since the two regions produced dissimilar commodities (because of the colonial pattern of international division of labour), the very comparison of labour productivities had to be not in physical but in value terms; and hence any such comparison would already incorporate the effect of unequal exchange. It would be ironical in short if the effect of unequal exchange was used to disprove the fact of unequal exchange.

This colonial pattern of international division of labour however raises a question with regard to the theory of unequal exchange itself. If the value of labour-power was lower in the periphery than in the metropolis, then why didn’t all activities shift from the latter to the former, resulting in a negation of the division of labour where the former was confined largely to the production of primary commodities while the latter produced manufactures?

This question arises even more strongly with regard to the unequal exchange theory of Arghiri Emmanuel, who argued that goods produced by the metropolis and the periphery exchanged against one another at prices of production, but prices formed on the basis of lower wages in the latter than in the former. Emmanuel in fact argued that mobility of capital equalized the rates of profit in the two regions even though each continued to remain specialized in its product-mix. The question this raises was: why didn’t this mobility of capital obliterate such specialization altogether, with a massive shift of manufacturing itself from the metropolis to the periphery?

This is precisely what is happening to an extent now under globalization, but it still does not remove the difference in the value of labour-power between the two regions (though their divergent movement has come to a stop, through metropolitan wages ceasing to rise with metropolitan labour productivity). The point here however is that Samir Amin’ project was not just to theorize unequal exchange but to look at capitalism as a global system passing through many phases (of which the current globalization is the latest), and to theorize the fact that the labour of the periphery remains super-exploited in all these phases. It was to carry Marx’s analysis forward by looking at accumulation on a world scale.

The unambiguous conclusion that emerges from Amin’s analysis is the need for the periphery to de-link itself from global capitalism if it is to achieve genuine progress, and nobody to my mind has emphasized the need for such de-linking more strongly and persistently than Amin. Japan, the only country outside the metropolis of that time to succeed in breaking into the ranks of the developed countries, could do so because it was not colonized. No other country has yet succeeded in this effort, though China, because of its background of far-reaching reforms in the Maoist period, is perhaps the only one according to him which has the potential for doing so (unless it is subject to military aggression by the West, a risk which he thought China and post-Soviet Russia faced).

Amin was clear that the current phase of neo-liberal capitalism had reached a dead-end. It was not that capitalism had necessarily reached such a cul de sac, but where we go from here, whether towards a new period of capitalist consolidation or towards socialism, would depend upon our praxis. It is for this reason that Amin until almost his last breath was himself actively engaged, and exhorting others to become actively engaged, in revolutionary praxis. He was even suggesting the formation of a new International so that revolutionary praxis across the world could be coordinated.

No account of Amin’s life will be complete without a reference to his immense warmth, generosity, and sheer comradeship. His enthusiasm, his laughter, and his remarkable energy for getting people together and pushing them in the quest for revolutionary praxis, was heart-warming, and infectious for anyone who came into contact with him. Talking to him was itself a learning experience, whether one agreed or disagreed: he would take one over a whole gamut of subjects, ranging from post-war France to the Bandung Conference, to the 2008 financial crisis. It was the joy of talking to a Communist who had kept his faith. He will be sorely missed by legions of friends, comrades and admirers.