Sri Lanka has historically signalled what other countries can expect to face amidst global economic…

Colombia: The search for elusive peace Jayati Ghosh

They march in tens of thousands, every Wednesday, through the streets of central Bogota: young and old; students and teachers; well-paid professionals, trade unionists and informal workers; healthy and disabled; urban and rural residents; family members and friends of the countless numbers who have been killed or maimed or have simply disappeared during this apparently endless war. They march for peace, and for a renewed attempt to find an agreement to settle the decades-old war between named and unnamed protagonists.

Ever since the peace agreement painfully negotiated between FARC (the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia) and the government was rejected by a wafer-thin margin in a referendum in which only 37 per cent of the electorate voted, they have been marching on a weekly basis. They march because, even though they may be sceptical of how much violence would be controlled by the peace agreement, they cannot countenance a relapse into the dark times of constant extreme insecurity. The old march to cope with the past and prevent its recurrence; the young march for their future.

In the Plaza Bolivar in the centre of the city, a giant white cloth is spread out, listing the names of at least 3000 dead, lovingly written down by their surviving friends; while others walk silently between life-size cut-out photographs of many other victims, all painfully young. In another part of the enormous square, a makeshift camp has been set up for people who have travelled from distant villages to make heard their exhaustion with war and their urgent plea for peace.

But to a casual foreign visitor, much of Bogota provides little indication that this is the capital of a country with such a violent history. The city’s location is scenic, with a constant view of the mountains framing its eastern boundaries; and comfortable, with an equable climate varying between 8 and 18 degrees Centigrade throughout the year. Situated on the “sabana” plateau at an altitude of 2625 metres, it is the third most elevated capital city in Latin America, after La Paz in Bolivia and Quito in Ecuador. Wide boulevards and leafy avenues connect posh new office complexes and attractive residential areas where the brick-red apartment buildings look approachable rather than oppressive, rubbing shoulders with super modern chrome-and-steel offices and “world class” malls. Sleek “Transmilenio” buses sweep through the main thoroughfares on their own special lanes. The environment seems clean and healthy, helped by the wind sweeping through the mountains that reduces atmospheric pollution. It has become a more “happening” city, now attracting international tourism keen to observe the country’s remarkable biodiversity. People are friendly and willing to enjoy themselves – despite the undercurrent of concern about the fragility of such enjoyment.

But this is the north of Bogota, the modern, 21st century city that reflects both the aspirations and the new reality of the elites and middle classes of the country. Aside from the odd homeless person or derelict drug addict on the streets in the central historic section, there is little to indicate that this country has the most extreme inequality of any country in the Americas (which is already the most unequal region of the world). The insecurities of the middle class are only slightly evident in this part of the city, as people drive through in cars with rolled up windows to prevent street attacks.

The poor are barely visible, mostly living in slums hidden away in the far south of the city, in shanty towns like Ciudad Bolivar that are untouched by municipal services. Better-off residents of Bogota scarcely venture into the poorer neighbourhoods of the south, which are home to the resident poor as well as migrants fleeing violence and lack of economic opportunity in their places of origin. Some argue that the division between the north and south of Bogota is a pale reflection of the even greater divisions across the country, between those who have benefited directly or indirectly from the rich natural resources of this country, and those who have laboured to enable that exploitation.

In fact, Colombia has a long history of violence. The Spanish conquistadores, known for their cruelty to local populations, exterminated many of the largely peaceful indigenous populations of Muisca and other tribes. The independent country was indeed born in blood, as a relatively small group of fighters led by Simon Bolivar took on the Spanish army to establish the independent state of New Granada. When the separate Spanish colonial entities of Quito (now Ecuador) and Venezuela were also militarily liberated from Spanish rule, the three together along with Panama formed the large independent country of Gran Colombia, with Bogota as capital and Bolivar as its President from 1819. The union did not survive Bolivar’s death in 1830, and the country that eventually became the Republic of Colombia continued to face the consequences of extreme internal strife.

Over the 19th century, civil wars killed around 3.5 per cent of the population. At the turn of the 20th century, the Thousand Days War resulting from the political conflicts between the Conservative and Liberal Parties resulted in an estimated hundred thousand deaths. On 9 April 1948, a date etched in the minds of all Colombians, the popular and progressive Liberal candidate for the presidency, Jose Elicier Gaitan, was assassinated, leading to massive riots in Bogota and elsewhere. This marked the beginning of the terrible period of La Violencia that went on until 1964, in which up to 200,000 people were killed. The wars between drug lords and their gangs controlling cocaine trade from the 1980s, and then the violence stemming from the emergence of revolutionary movements like FARC are estimated to have resulted in around 220,000 more deaths – but no one knows the exact number, as so many people also disappeared without a trace. At the peak of the drug wars in the early 1990s, the homicide rate in Antioquia (and its capital Medellin, home of the infamous cartel led by Pablo Escobar) was as high as 400 per 100,000 people in a year.

Some argue that Colombia’s difficult and complex geography – with its three mountain ranges and separate coastal regions supporting local isolation – has contributed to the lack of social and political cohesion that allows such violence to continue. Others point to the country’s extreme economic inequalities, which create both the will to power of small elites and the anger and resistance of deprived and exploited classes and groups. Still others note that – like many other countries blessed with abundant natural resources – the people of Colombia have suffered from vicious competition to control those resources and the labour of the people used to extract them. The endemic corruption and apparent inability of the state to protect its citizens has also fuelled private and group-based violence.

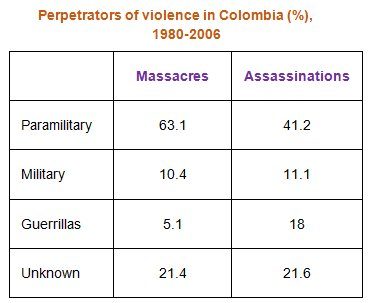

In much of the global discussion around war and peace in Colombia, the role of FARC is typically given great significance, as the central element that would ensure resolution of conflict. Yet inside Colombia it is generally known that the paramilitaries (controlled by landed elites or cocaine dealers or mining barons trading in coal, gold and emeralds) have been and continue to be responsible for much more violence. As the table shows, they have been responsible for the bulk of massacres and assassinations through the worst years of violence in the past four decades. Since much of the media is controlled by those who also run paramilitary organisations, it has disproportionately highlighted the guerrilla violence and downplayed that by paramilitaries and that by the state forces that have often been their allies.

Source: http://colombiareports.com

Source: http://colombiareports.com

FARC and other militant groups like ELN (National Liberation Army) originally began as idealistic left-wing responses to the extreme exploitation of local people by landed elites and their urban business counterparts. They were originally inspired by egalitarian doctrines of various kinds, which eventually coalesced into a kind of Marxism. Some argue that they were driven to violence by the severity of the counter-reaction, which forced them to take up arms to fight for what were simply the democratic rights of citizens. But over time, as they were forced to take refuge in mountains and inaccessible areas and became guerrilla fighters, these groups too became relatively distant from the people they wished to fight for. Local people typically feel trapped in the violent contestation, with guerrilla forces kidnapping children to add to their numbers and others kidnapping for extortion; while government and privately-controlled militias wreak terrible punishment on those seen to be harbouring or enabling terrorists. Both sides seek to terrorise and control the villagers. The sheer brutality of the punishments and killing, especially by the paramilitary organisations, made daily life traumatic and bare physical survival often seem like a miracle.

The United States has much to answer for in all of this. US users of cocaine provided the financial backing for drug mafias and other crime syndicates, and the US government also indirectly supported these and other paramilitaries in the name of fighting communism. It then sought to balance this out by providing hardware and funds to the Colombian army, which was to fight both the revolutionary groups and the paramilitaries. Plan Colombia pushed by the Bill Clinton government (and subsequently enthusiastically accepted by the government of previous President Alvaro Uribe) intensified the violence and pushed aside all concerns of human rights abuses by agents of the state in the effort to flush out opposition. Coca fields – a basic source of the meagre income of much of the peasantry – were aerially sprayed with poison to stop cultivation; extreme military force decimated both rebel groups whose numbers have dwindled, and innocent local people who have become collateral damage. The desolate peace this brought about was inevitably fragile, and the associated trampling on basic rights has left an unhappy and bitter legacy that leaves much work left to do for democratic institutions and social activists.

This is the context in which the current Colombian government led by Juan Manuel Santos (who was the Defence Minister under Uribe, but has since distanced himself) and the FARC rebels signed a ceasefire deal on 23 June 2016, after more than four years of negotiations conducted in Havana, Cuba. This was based on a six-point plan, in which FARC agreed to demobilise and give up weapons in exchange for political participation– effectively exchanging bullets for ballots in what was promised to be a more transparent political process. FARC members would be provided financial assistance to reintegrate into society and FARC would get some funds to enable it to transit into a political party.The issue of immunity has been a fraught one – while amnesty would be provided to those who have committed political crimes, the agreement excludes the granting of amnesties for war crimes and crimes against humanity and would in fact end immunity for the most serious crimes.

A comprehensive security system would ensure security guarantees for all those participating in politics, including human rights and other social activists (which are still very dangerous activities in Colombia). There would be a Truth Commission and a process of assistance and reparation for victims of the conflict. Democratic rights were to be secured for social activists and trade unionists, ensuring their physical security, right to information and freedom to protest. The agreement contains clauses on the promotion of a democratic and participatory political culture based on respect for democratic values and principles, transparent management of public institutions and integration of marginalized communities like women, LGBT, Afro-Colombians and indigenous peoples. In other words, much of the peace agreement contains promises that should be provided within the framework of the 1991 Constitution already adopted by Colombia, but only partially implemented.

A crucial issue in the peace agreement relates to land distribution. Colombia is one of the most unequal countries in the world in terms of rural landholding, and the Gini coefficient for land ownership increased from the already high 87.7 per cent in 2000 to 88.5 per cent in 2009. According to the 2014 Census, less than 1 per cent of the landowners who have holdings of more than 500 hectares hold more than 77 per cent of the land, while around three-quarters of the peasantry is crowded into small holdings of less than 5 hectares. Many small holders lost their land through forcible expropriation and simple takeover of their lands after violence. The peace agreement calls for significant changes to enlarge access to land and its use as well as comprehensive development packages for small holders. A Land Fund would be created through recovery of illegally acquired land, judicial expiration of ownership, expropriation of unexploited land and other expropriation for social interest. This land would be redistributed to landless or land-poor rural people, and would be inalienable and non-transferable for a period of seven years. Property titles of small and medium land holders would be formalised. This process would be accompanied by a comprehensive subsidy, credits, technical assistance, housing, marketing and access to means of production provided by the government, as well as a food security system with programmes against hunger and malnutrition.

To the surprise of many, the plebescito or popular referendum held on 2 October narrowly rejected the peace agreement by a margin of only 0.4 per cent, while nearly two-thirds of voters did not vote at all.

Ex-President Uribe and right-wing forces had campaigned against the peace deal, on the grounds that it gave too many concessions to FARC. However, there are those who argue that the real resistance to the agreement has come from rightwing paramilitary groups. The agreement promises a Special Investigation Unit within the Attorney General’s office to dismantle all criminal organizations and paramilitary successor organizations, which would investigate, prosecute and indict all criminal organisations responsible for homicides, massacres, gender violence or attacks on social and political movements. Alvaro Uribe’s brother is rumoured to be associated with one of paramilitary groups and there have been accusations that the 2006 re-election of Uribe himself was financed by paramilitaries, specifically by their umbrella organisation the AUC (United Self-Defense Forces of Colombia), which has since been dismantled.

Despite the narrow referendum loss, the peace process in Colombia is not over. While the process of laying down of arms by FARC has been halted for now, the ceasefire continues, and the government is also negotiating with the ELN in Havana. Uribe and the other opposition now face charges of electoral fraud for wilfully misleading the public on aspects of the peace deal, and have been sidelined in the parliament. There is hope – especially among the marchers in Bogota and other cities and towns across the country – that the agreement can be tweaked and slightly altered to meet some pressing concerns, and then finally implemented. Despite this recent setback, the public desire for peace appears to be overwhelming, along with the felt need for restitution.

Readers in India will recognise many of these features: the history of aggressive exploitation of natural resources and of the local people; the lawlessness and lack of recourse to justice; the aggression and impunity of paramilitary organisations set up by the powerful; the rise of violent alternatives among the oppressed; the fierce suppression of these by the state apparatus; and the consequent cycle of apparently unending violence. Particularly when looking at the comparative perspectives of New Delhi and say, Bastar in Chhattisgarh, the similarities are eerie. Perhaps the continuing attempts at achieving peace in Colombia against all odds can provide some hope and insight into our own sites of tragedy and violence.

(This article was originally published in the Frontline Print edition: November 25, 2016)