This year marks 30 years after the Beijing Declaration and Platform for Action (1995) of…

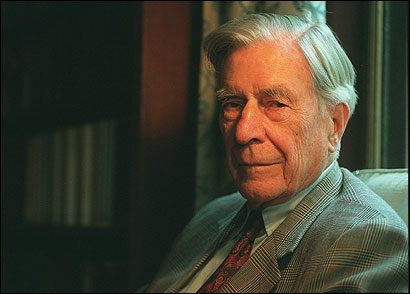

John Kenneth Galbraith, writer, economist, dies Mark Feeney

John Kenneth Galbraith (1908-2006)

John Kenneth Galbraith, a towering figure in American intellectual life whose astringent wit and elegant iconoclasm graced the academic and political scene for seven decades, died yesterday at Mount Auburn Hospital in Cambridge. He was 97. His son, Alan Galbraith, told the Associated Press his father died of natural causes.

”He had a wonderful and full life,” his son said.

”This is terribly sad news,” his neighbor author Anne Bernays said last night. ”He was an incredibly smart man. He knew everything, he remembered everything, and he got you on everything. He always had the last word, but in a wonderful way.”

Though he called his autobiography ”A Life in Our Times” (1981), another Galbraith title better encapsulated his politics: ”Annals of an Abiding Liberal” (1979).

”I hear that in your country you are considered a man of the left,” Leonid Brezhnev once said to him. ”I invite you to the Soviet Union so you will have the experience of being a reactionary.”

That would have been a novel experience for Dr. Galbraith. He worked in the Roosevelt and Truman administrations, wrote speeches for Adlai Stevenson, served as ambassador to India during the Kennedy administration, turned down Lyndon B. Johnson’s offer of the directorship of the Peace Corps, and as a self-described ”independent operator at the guerrilla level of American politics” played notable roles in the presidential campaigns of Eugene McCarthy and George McGovern. He was also one of the first and most vocal opponents of US involvement in Vietnam.

Dr. Galbraith enjoyed a lasting association with the Kennedy family. He was a pillar of the New Frontier, and his presence did much to lend it its academic cachet. The president, Dr. Galbraith once recalled, ”was pleased to have me in his administration but at a suitable distance such as in India.”

The Harvard economist, who said he revised each of his books at least five times, was as much man of letters as social scientist. Writing in a rigorously burnished style reminiscent of the 18th century, he resembled a latter-day Enlightenment philosophe, a thinker as devoted to crafting pellucid prose as shaping public policy.

Political appointments and pronouncements notwithstanding, Dr. Galbraith’s 30-some books were what made him internationally famous. Further enhancing his academic superstardom were a 6-foot-8-inch frame and what he once described as a ”long, liturgical face” that could have been hewn from stone. On page or stage, John Kenneth Galbraith was a formidable figure.

His worldliness and wide-ranging interests put him at odds with the ever-increasing specialization of contemporary economics. He received his colleagues’ highest honor in 1971, being named president of the American Economics Association, but Dr. Galbraith’s fondness for the generalizing epigram and distaste for quantification meant his greatest following was among lay readers rather than fellow economists.

Even more than John Maynard Keynes (and Dr. Galbraith was one of the first US disciples of Keynesian economics), it was Thorstein Veblen, the author of ”The Theory of the Leisure Class,” a classic amalgam of social science and mockery, who provided Dr. Galbraith with his model: the economist as social critic.

”I never imagined that there was any point to being an economist if no one was aware of what you were thinking,” he once said. ”Nothing so protects error as an absence of readers or understanding.” Indeed, two of Dr. Galbraith’s favorite novelists, Anthony Trollope and Evelyn Waugh, had a more discernible effect on his work than any economist did. Their wit, clarity, and keen eye were qualities he prized highly — and consistently demonstrated throughout his own work.

Dr. Galbraith was born in the rural Ontario town of Iona Station on Oct. 15, 1908, the fourth child of Scottish immigrants William A. and Catherine (Kendall). In his book, ”The Scotch” (1964), Dr. Galbraith memorably evoked the Scottish-Canadian culture he grew up in. It was one in which ”to call a son something other than John was to combine mild eccentricity with unusual imagination.” As it happened, Dr. Galbraith disdained use of his first name; to friends, he was ”Ken.” Harvard president Nathan Marsh Pusey once made the mistake of calling him ”John”; Dr. Galbraith thereafter greeted him as ”Marsh.”

He attended Ontario Agricultural College (now the University of Guelph), which he once described as ”not only the cheapest but probably the worst college in the English-speaking world.” A fellowship to do work in agricultural economics, his undergraduate field, took him to the University of California at Berkeley. After earning his master’s and doctoral degrees there, Dr. Galbraith came east in 1934 to spend the summer working in Washington for the Agricultural Adjustment Administration and then assume an instructorship in economics at Harvard.

On Sept. 17, 1937, Dr. Galbraith married Catherine Merriam Atwater. Three days earlier he had become a US citizen. During the academic year 1937-38, he was a Social Science Research Council Fellow at Cambridge University, England.

In 1939, he became an assistant professor of economics at Princeton. He returned to government service a year later, first as an adviser to the National Defense Advisory Committee and then as deputy administrator of the Office of Price Administration. Enjoying ”considerable and welcome power” at OPA, Dr. Galbraith soon ”reached the point that all price fixers reach — my enemies outnumbered my friends.”

He left government to join the board of editors at Fortune magazine and in 1946 directed the State Department’s Office of Economic Security Policy. In between, he headed the US Strategic Bombing Survey. ”At the end of 1945,” Dr. Galbraith later wrote, ”it is possible that I knew more about the drained and shattered economies of both Germany and Japan than anyone alive.”

That remark exemplifies Dr. Galbraith’s legendary self-assurance. A 1955 FBI security check summed up its subject thusly: ”Investigation favorable except conceited, egotistical, and snobbish.” President Kennedy once asked Dr. Galbraith his opinion of an article that profiled the economist in The New York Times. He had liked it well enough, Dr. Galbraith said, but wondered why it had had to call him arrogant. ”I don’t see why not,” the president said, ”everybody else does.”

Dr. Galbraith returned to Harvard in 1948 as lecturer, became a full professor the next year, and Paul M. Warburg professor of economics in 1959. He retired from teaching in 1975.

During the ’50s he published a number of books: ”American Capitalism” and ”A Theory of Price Control” (both 1952), ”The Great Crash” (1955), which one reviewer called the ”wittiest book ever written by a professional economist,” and ”The Affluent Society” (1958). The latter, with its critique of a consumer-driven economy of excess, made him a celebrity. It was translated into a dozen languages and went on to sell some 1.5 million copies. It also added a new phrase to the language, ”the conventional wisdom,” which its creator spent the rest of his life subverting.

Dr. Galbraith remained politically active throughout this time. He was a founder of Americans for Democratic Action in 1947, later serving as its chairman from 1967-68, and advised Stevenson, the Democratic presidential nominee in 1952 and ’56. ”I want you to write the speeches about Nixon, Ken,” the candidate said, ”because you have no tendency to be fair.”

After 1956, Dr. Galbraith transferred his allegiance to the junior senator from Massachusetts. At the ’56 convention, Kennedy had narrowly lost the vice-presidential nomination, a loss owing to a stand on agricultural price supports Dr. Galbraith had warned against. Afterward, Kennedy told him, ”I don’t want to hear about agriculture from anyone but you, Ken. And I don’t want much to hear about it from you either.”

As a reward for his work during the 1960 campaign, Dr. Galbraith was sent to New Delhi. ”The job of an American ambassador,” he later explained, ”is to maintain civil communication with the government to which he is accredited and, to the extent that personality allows, to personify the majesty and dignity of the United States. No one should suppose that this is either intellectually or physically taxing.”

Indeed, Dr. Galbraith managed to write no fewer than four books while in India: ”The Scotch,” ”Economic Development” (1962), ”Ambassador’s Journal” (1969), and the first of his three novels, ”The McLandress Dimension” (1963), which he published under the pseudonym Mark Epernay. The other novels are ”The Triumph” (1968) and ”A Tenured Professor” (1990). He also began work on ”Indian Painting” (1968). ”It is my only writing to which, to my knowledge, no one has ever taken serious exception.”

Dr. Galbraith returned from India in 1963. That spring he and his wife began what became a celebrated Cambridge tradition: the annual Harvard commencement party at their Francis Avenue home. ”We don’t send out invitations,” Dr. Galbraith explained at the 25th-anniversary edition of the event, ”just reminders to our friends.” Those friends would usually number in the vicinity of 300, with a sprinkling of heads of state and Nobel Prize laureates.

In 1967, Dr. Galbraith published what he considered to be his most important book, ”The New Industrial State” (1967). It, too, was an international bestseller, with its examination of ”the economic, political, and social theory of that part of the economy by now preempted by the large corporations.” Along with ”The Affluent Society,” it formed a trilogy completed in 1973 with publication of ”Economics and the Public Purpose.”

”The Age of Uncertainty,” a multipart television series on the history of economics that Dr. Galbraith did for the BBC, brought him a new audience when it was broadcast in 1977. It also led to two more books: one bearing the same name as the series and ”Money: Whence It Came, Where It Went” (1975).

Dr. Galbraith received honorary degrees from numerous institutions. ”My only rule in the matter,” Dr. Galbraith liked to say, ”is to have more honorary degrees than Arthur Schlesinger,” his longtime friend and Kennedy administration colleague.

He was a member of the American Academy of Arts and Letters, and its president from 1984-87; a fellow of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences; and a member of the American Agricultural Economics Association, the Saturday Club, the Century Club of New York and the Federal City Club of Washington, D.C.

President Clinton awarded him the Presidential Medal of Freedom, the nation’s highest civilian honor, in 2000.

Along with his Francis Avenue home, Dr. Galbraith had a 247-acre farm near Newfane, Vt., and a chalet in Gstaad, Switzerland, where he was an active downhill skier. He noted that he brought to the sport ”enthusiasm, considerable awkwardness and some slight danger to anyone in the vicinity.”

In addition to his wife and son, Alan, Dr. Galbraith leaves two sons, Peter and James Kenneth. Another son, Douglas, died of childhood leukemia.

(This article was originally published in the Boston Globe : April 30, 2006)