When Azerbaijan as the Presidency of this year’s Conference of Parties (COP29) held at Baku,…

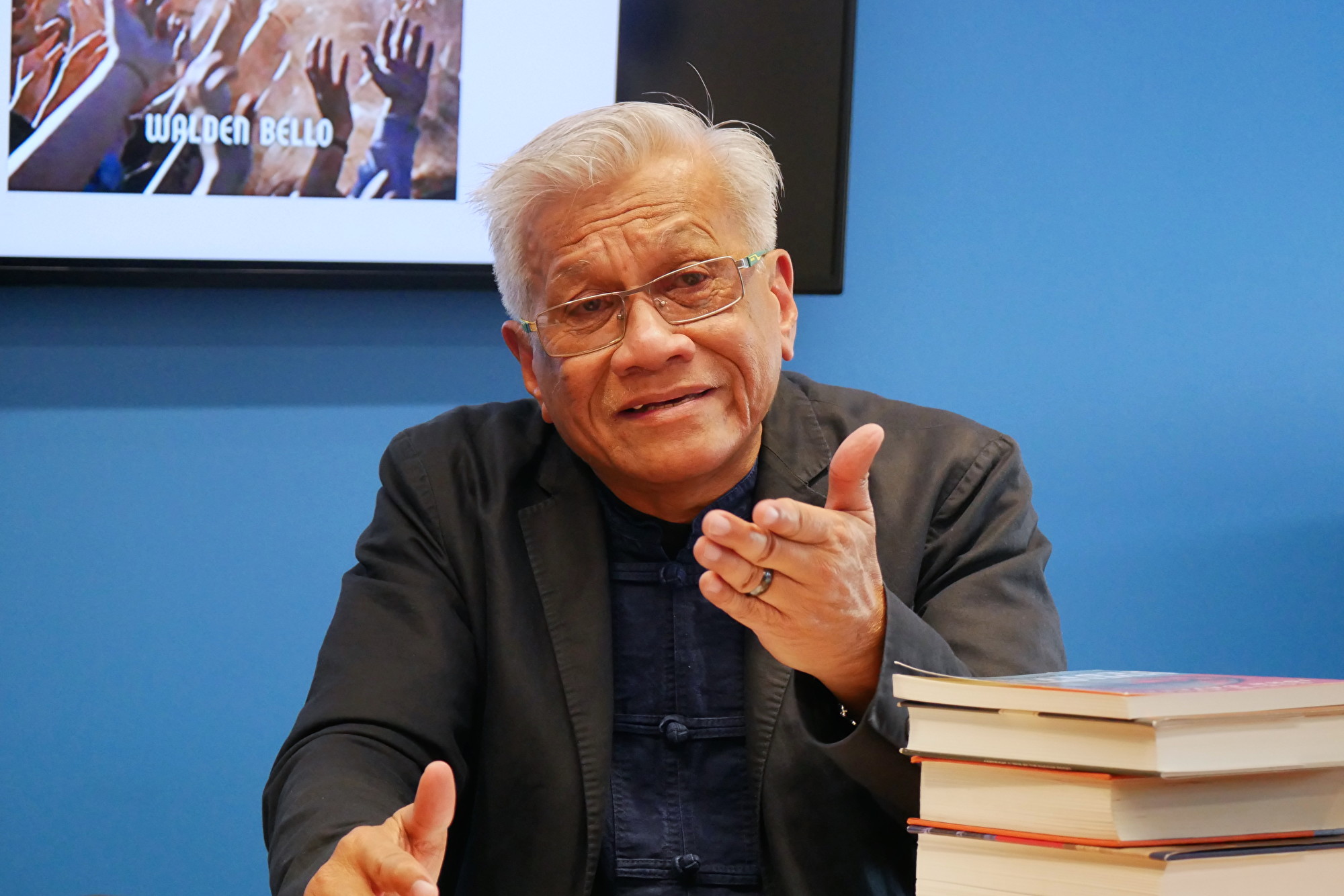

How we can Change the World after the Pandemic An interview with Walden Bello by Francesca Lancini

Walden Bello: a life lived in the name of human rights. From fighting dictatorship in the Philippines to developing proposals for a more equitable post-pandemic world: if actions determine a human being’s greatness, he is, in all respects, a giant.

Born in Manila in 1945, Bello has played an important role in the history of the global progressive Left. A sociologist, academic, environmentalist and activist, he’s anticipated historic changes thanks to his sharp intuition. As a university student in Chile, he saw the far-right overthrow President Salvador Allende. In the US, where he currently teaches, Bello uncovered evidence that the World Bank and the IMF supported Ferdinand Marcos’ authoritarian regime in the Philippines (1965-1986) and his book inspired the popular movement that toppled it.

Bello was the first to point out the disastrous outcomes of the “Asian economic miracle”, starting with the 1997 financial crisis – a precursor to other stock market collapses. In 1999, he was the victim of a beating at the hands of police in Seattle while protesting for reform of the World Trade Organisation (WTO), and he also risked his life during the crackdown on demonstrations at the Genoa Social Forum in 2001. But he never gave up. In 2003, he was presented with the Right Livelihood Award – also known as the “Alternative Nobel Prize” – and he served in his country’s congress between 2009 and 2016. Naomi Klein has referred to him as a source of inspiration. “In those moments when our progressive values come under attack or ridicule, it’s then that we’re tested. And we have to affirm them,” he tells us in this exclusive interview.

Bello spoke to us from Bangkok, where he directs a think tank called Focus on the Global South. “Here I got to observe how cooperation between civil society and public health authorities produced a robust response to the crisis”. He shares his vision of the world during and after the coronavirus pandemic, the latest crisis that has forced us to learn from the past and rethink the future.

Where have you spent the lockdown? How has this experience been for you?

I was stranded in Bangkok, Thailand. But it was a good thing because I got to observe how cooperation between civil society and public health authorities, building on trust developed over some five decades of successful public health campaigns, produced a robust response to the crisis. Thailand has contained Covid-19, with only slightly over 3,200 infections and “just” 58 deaths. Contrasted with the hundreds of thousands of infections and thousands of deaths in the US and Europe, this is simply amazing.

But it’s not just Thailand…

Taiwan has registered very few deaths and Vietnam none at all. In all three cases, it wasn’t a case of authoritarian leaders giving orders from above that proved decisive. In fact, the military leadership in Thailand made blunders early on. What made the difference wasn’t just the use of face masks, which in Thailand was at 95 per cent (as opposed to 15 per cent in the UK and 48 per cent in the US). It was the public health authorities working closely at the grassroots level with civil society that stabilised the situation and contained the spread of the virus. Hygiene and a popularly supported public health system were key. The political leadership and the Emergency Decree it issued were, in fact, superfluous.

You said this pandemic, the second crisis in a decade, shows us once again that “neoliberalism is dying”. How can we convince people of this?

The pandemic has swept a world which hasn’t yet recovered from the 2008 global financial crisis and its aftermath. Before the pandemic, there was already massive disillusionment in the US owing to the fact that the government favoured bailing out big banks instead of bankrupt homeowners and that unemployment stayed very high long after 2008, owing to neoliberal resistance to government spending. Southern and Eastern Europe were in the grips of austerity programmes designed to squeeze the population of the funds needed to repay European public institutions and the IMF, which had bailed out German and French banks. The last decade has seen the world economy in a state of “secular stagnation,” as the International Monetary Fund admitted. Then the pandemic hit and the already troubled economic systems froze up. GDP dropped from four to seven per cent in major economies in the first quarter of this year, the largest decline in decades, and the most optimistic estimates see a decline in global GDP of at least six per cent for 2020. Millions have been thrown into the ranks of the unemployed – close to 30 per cent of the US workforce, for instance.

How are governments reacting to this situation?

Governments were forced to go beyond their responses to the financial crisis and intervened on a massive scale with stimulus programmes to prevent economic catastrophe followed by a political apocalypse. The contrast between the anaemic response to the financial crisis and the relatively vigorous – though still limited – response to the pandemic has been an eye-opener for people. It has shown what is possible when governments disregard market solutions and opt for decisive action. In sum, already shaken by the financial crisis and its aftermath, the credibility of neoliberal thinking and policymaking has been battered even further by the pandemic. The only question is whether the death of neoliberalism will be fast or “slow” as economist Dani Rodrik puts it.

A huge economic crisis is forecast after two months of strict lockdown in Italy. How can the system be so fragile? Up to the 1980s, factories, shops and services would close for at least one or two months over the summer, and this happened every year.Economies in both the global North and global South are much more fragile today than in the 1970s and 1980s because of three things. First, the globalisation of production saw the deindustrialisation of many economies in the North, as labour-intensive processes were shifted to the South where wages were much lower. Global supply chains then replaced domestic production both in industry and agriculture: they seem to be efficient but they’re actually very fragile, susceptible to disruption by wars, disasters and pandemics. When Covid-19 hit, China’s production lines stopped, creating massive shortages of essential goods, including face masks and other personal protective equipment, in many countries. And now comes the disruption of global food supply chains throughout the world, leading to the possibility of food shortages and hunger in certain areas over the next few months.

And the other two reasons?

Second, neoliberal policies gutted consumption everywhere, and we all know that consumption is the engine of demand. Wages were stagnant for two decades in the North and people resorted to massive borrowing. When the 2008 financial crisis hit, borrowing was no longer an option, forcing large numbers of people to lose their homes and fall into poverty. At the same time, policies designed to increase the profit rate led to greater and greater inequality.

Third, with industry stagnant, investments went to finance, where greater profits were to be made from speculation. While contributing only about 5 to 10 per cent of GDP, the financial sector in the US cornered some 40 per cent of all corporate profits. Investing in finance, however, doesn’t create new value. Profit is made from speculation or from betting on the rise of the price of assets compared to their real value. This means these prices eventually collapse, financial crisis ensues and on its heels comes a sharp downturn in the real, productive economy.

How can we recover?

Recovery will be a very difficult prospect, and the only sustainable recovery possible is one that departs radically from the principles of neoliberalism and involve a great degree of state intervention. The question is, will that state intervention be progressive, leaning towards a socialist direction, or repressive, leaning towards a fascist one?

Can you explain your “alternative way” to replace a dying neoliberalism system? What do you mean by “deglobalisation”?

I see three possible routes being offered to people to get out of the current crisis. One is a restoration of neoliberal policies, which will be very difficult since they simply won’t deliver anything except greater inequality, which people will no longer accept. A second route is the progressive one, where greater state intervention takes place in the context of the democratisation of economic decision-making, greater popular empowerment, greater equality and the adoption of climate-friendly economic policies.

In recent years, there have been many exciting policies or paradigms proposed to reach these ends, such as degrowth, food sovereignty and deglobalisation. I’ve been associated with deglobalisation, which seeks to make domestic demand created through egalitarian measures the centrepiece of the economy. Another aim is to protect industry, agriculture and jobs from dislocations created by uncontrolled industrial and agricultural imports. The third route, and the most worrying, is the fascist route. Here, state intervention in the economy takes place in the context of a policy that opportunistically hijacks the social welfare measures associated with the Left. Crucially, however, it states that only those with the “right” skin colour, who come from the “right” ethnic stock or belong to the “right” culture deserve to enjoy those measures. Minorities and migrants are scapegoated as the source of people’s troubles and social disorder. The race to replace a dying neoliberalism is between the progressive option and the fascist route.

You focus on mass psychology to understand social phenomena. What do you think is happening today?

In 2008, people were shocked when the financial crisis hit after nearly two decades of relatively smooth sailing. Although inequalities were growing under the surface, the public wasn’t so alienated from the neoliberal capitalist system. Today things are different. In the North, people are growing tired. And in the South of course, continuous neoliberal structural adjustment programmes by the IMF and the World Bank since the late 1970s has left very few people with the hope of development under neoliberalism. The buoyant popular mood that existed during the era of decolonisation from the 1950s to the 1970s has been banished.

The extreme Right is taking advantage of global discontent in different continents and you see similarities with the 1930s. Can you tell us what these are? How can we discourage a repressive revival?

Unfortunately it’s the extreme Right that is currently best positioned to take advantage of global discontent. This is because, even before the pandemic, extreme Right parties were opportunistically cherry-picking elements of the anti-neoliberal stance and programmes of the independent Left but putting them within a right-wing gestalt (an organised whole, ed.). Examples of this trend include the critique of globalisation, expansion of the welfare state and greater state intervention in the economy. So in Europe you had radical right-wing parties – among them Marine Le Pen’s National Rally (formerly the National Front) in France, the Danish People’s Party, the Freedom Party of Austria, Viktor Orban’s Fidesz Party in Hungary – abandoning the parts of the old neoliberal programmes that advocated for liberalisation and less taxation.

They then began proclaiming they were for the welfare state and more protection of the economy from international engagements, but exclusively to the benefit of the people with “right skin colour”, the “right culture”, the “right ethnic stock”, the “right religion”. Essentially, it’s the old National Socialist class-inclusivist but racially and culturally exclusivist formula, whose consummate practitioner at present is Donald Trump. Unfortunately, this works in our troubled times, as shown by the unexpected string of electoral successes of the far-right that have pirated large sectors of social democracy’s working-class base.

And the far-right in Asia?

Two leaders have emerged in the global South who illustrate facets of the far-right dynamic much more evidently than in the North. President Rodrigo Duterte of the Philippines and India‘s Prime Minister Narendra Modi both belong to the extreme Right. They’re very popular partly because they’ve been able to harness people’s discontent with the failings of liberal democracy, especially the gap between its promise of equality and the reality of deep inequality and wretched poverty. They’re charismatic individuals who have convinced the vast majority of the citizenry that their anti-liberal programmes are the solution to the ills of both societies. We’re witnessing a paradox whereby free elections are resoundingly confirming their hold on power and leading to power being increasingly concentrated in their hands.

Both of them are opposed to fundamental democratic principles: due process in the case of Duterte and secularism in that of Modi.

These personalities may not deliver on their promises and their economic policies may be causing major problems, like those caused by Modi’s demonetisation programme. But no matter; they get thumping majorities. In this sense, democracy, paradoxically, strengthens authoritarianism. These personalities have cross-class appeal, and this is why we must consider charisma as a central reason for their success, though we on the Left tend to be sceptical or even hostile to explanations based on charismatic appeal. Charisma is a social relationship between the leader and the led. We must try to understand it; otherwise, we’ll never understand why in the midst of the heaviest bombing in the history of war, the vast majority of the German people, including the young (later Social Democrat) Gunter Grass remained loyal to Hitler.

How can the left-wing reconnect to people?

First of all, I think we must admit that while our side has many good ideas about how to transform the world, these ideas haven’t been translated into a critical mass on the ground. Just as the Right learned from the Left, maybe we should also see if there are lessons that the success of the Right offers the Left. History is a complex dialectical movement, and there are often unexpected developments. These can open up opportunities for those bold enough to seize them, to think outside the box, and who are willing to ride the tiger on its unpredictable route to power. There are many such people on the Left, especially among the younger generation.

The new Left has to confront the reality that reason – which has always been its strength – is currently of limited value when it comes to winning the political power needed to restructure society. Furthermore, it has to reconsider the place of emotions in politics, something it has always been suspicious of, often rightfully so. Can the Left compromise with its longstanding belief in the rational voter or rational citizen while still remaining faithful to its values? When Antonio Gramsci says “pessimism of the intellect, optimism of the will,” I think he’s referring to this compromise. But perhaps, in the short term, the lesson the Left must learn is that history is unforgiving and it rarely tolerates making the same mistake twice. Should progressives again allow discredited social democrats in Europe, and Obama and Biden-type Democrats in the US to drag progressive politics back to a new compromise with a dying neoliberalism, the consequences could be truly, truly fatal.

In “Never let a good crisis go to waste”, the report you wrote for the Transnational Institute, you explain that the pandemic is an opportunity for embracing food sovereignty. Many poor countries can produce food by and for themselves. But how can we deal with corporations? Do we need new global political rules?

The pandemic’s disruptive impact on global food supply chains has coincided with the drastic weakening of the WTO. This is due to the United States’ refusal under Trump to adhere to multilateral trade rules and preference for bilateral agreements, often reached through the threat of coercion. While neoliberals are decrying this turn toward unilateralism on the part of the US, it’s actually positive for the global South. The current situation offers a great opportunity for developing countries to free themselves from complying with the WTO free trade rules that have severely damaged their agricultural sectors over the last 25 years. These countries can reintroduce quotas or high tariffs on imports to protect their agricultural producers and move towards food self-sufficiency and food sovereignty. That is, towards people’s right to determine the priorities, practices and patterns of food production and consumption.

In the ongoing trade war, the US has attacked another economic giant, China. How do you consider Beijing’s role during the pandemic?

The fact that the Communist Party was trying to suppress information about the pandemic when it began in Wuhan was deplorable and became a strong lesson to the world about the dangers of authoritarianism. At the moment, both Beijing and Trump – with his deplorable anti-scientific and racist acts, like calling the coronavirus “Kung Flu” – are seen as irresponsible and untrustworthy.

You’ve criticised China’s Belt and Road Initative (BRI) because it will disrupt many ecosystems. This worrying fact could also lead to further instances of zoonosis, the mechanism by which the coronavirus made the jump to humans.

According to one study, the Belt and Road Initiative’s planned network of roads, railways and pipelines in Eurasia would introduce more than 800 invasive species in local ecological systems, leading to their destabilisation. But the BRI isn’t so much a grand plan for domination but rather a grandiose anachronistic transference to the 21st Century of the technocratic, state socialist and developmentalist mindset that produced the Hoover Dam in the US, massive construction projects in Stalin’s Soviet Union during the 1930s, the Three Gorges Dam in China, Narmada Dam in India and Nam Theun 2 Dam in Laos. These are testaments to what Arundhati Roy calls modernity’s “disease of gigantism” and that others have branded as “neodevelopmentalism” or “extractivism”.

How should democratic nations deal with Beijing?

As for how to relate to China, I think very frank criticism of the negative aspects of China’s domestic, economic, foreign and military policies is the best posture we can adopt to help it avoid following in the footsteps of the imperialist West. Being quiet and accommodating to Beijing will merely encourage the ultra-nationalistic elements in the leadership in believing they’re right.

You took part in the Genoa Social Forum in 2001. What do you remember of that experience?

Seattle in 1999 and Genoa in 2001 were the high points of the anti-globalisation movement. The Italian state responded in a very repressive fashion: I still remember how thousands of people marched bravely through the narrow streets in a very disciplined manner while the Carabinieri (one of the country’s main law enforcement agencies, ed.) blasted them with tear gas in an extremely irresponsible way. Had people stampeded, there would have been many deaths and injuries. I myself was detained by the police and was nearly hit by a police car that was careening wildly through a narrow street to clear it of demonstrators. I had to flatten myself against a wall and only around six inches saved me from possibly entering eternity.

Was that repression planned to destroy progressive movements, those advocating for “another possible world”?

It wasn’t the repressive response that took the wind from the sails of the anti-globalisation movement. It was the September 11 attacks that broke our momentum. We were, in a very real sense, the biggest collateral damage inflicted by them. In the aftermath, elites were able to effectively position anti-terrorism as the centrepiece of their response to the global disaffection embodied by the anti-globalisation movement. The sense of initiative didn’t return to the Left until the 2008 global financial crisis produced the Occupy Movement.

You’ve fought many battles in the name of human rights. How do you still find the strength and hope?

To be honest, I have many moments of doubt these days when I see people stampeding to the Right. I ask myself, am I on the right track? It’s very natural to experience moments of doubt. But it’s during these moments, when our progressive values come under attack or ridicule, that we’re tested and we’re faced with the choice of either retreating from them and keeping silent, or affirming them. It’s when progressive values are unpopular that the real test comes for us. But I’m also aware of my limitations or those of my generation, the 1968 generation that dominated the global Left from the late sixties to the early 2000s. I realise that we’re working with – or imprisoned in? – old and dated paradigms of analysis and organising. It will take leaders from today’s generation to take us forward, younger people who are able to do what we haven’t been able to do, and who may emerge in unorthodox and unpredictable circumstances.

(This interview was originally published in LIFEGATE on 17 July 2020)