The World Bank set its US ‘dollar-a-day’ poverty line using its 1990 data. Despite many…

Are Distress Deaths Necessary Collateral Damage of Covid-19 Response? Vikas Rawal, Kathik A Manickem and Vivek Rawal

The Experience of First Three Weeks of the Lockdown in India

India implemented a national lockdown to contain the spread of COVID-19 pandemic. The lockdown was announced suddenly, and without a prior warning to give time to people to prepare for it. The suddenness with which lockdowns were implemented does not seem to have been part of any plan but a reflection of the lack of planning. On March 16, the Prime Minister asked people across the country to self-quarantine just for a day, on March 22. In the evening of March 22, he announced that some districts were being locked down. And then on the evening of March 23, he announced a complete, 21 day, country-wide lockdown starting midnight of March 24. As we write this, there is news that it is being extended for another two weeks, until April 30.

Response to Covid-19 necessitates social distancing, testing, quarantine or isolation as necessary means to slow down or control the spread. Even though complete lockdown of all economic activities as an effective means to achieve the above is arguable, this article focuses on an unfolding socio-economic crisis in the country as a vast majority of workers, who are employed in the informal economy, found themselves robbed of their means of livelihood with nothing to fall back on. As enterprises and establishments downed their shutters and the economic activity came to a grinding halt, small producers and workers across all sectors found themselves robbed of their livelihood, and in many cases, stranded far away from their families.

The distress created by this sudden imposition of a prolonged national lockdown has resulted a surge in distress deaths. This surge, starting on March 25th, the first day of the national lockdown, has continued unabated throughout the three weeks of the lockdown. This article is an attempt to systematically examine the distress deaths caused by the imposition of a prolonged country-wide lockdown without preparation and planning. In this article, we refer to deaths because of COVID infections and co-morbidity as infection deaths and deaths due to distress caused by mitigation strategies as distress deaths.

Sources of data and their limitations

The data on distress deaths has been compiled by us using newspaper and online reports with the help of many friends and colleagues. The dataset is regularly updated and is available at https://coronapolicyimpact.org. Along with us, a few other groups active on social media are also compiling similar data. All these datasets are public and provide the original source of news for each case. We cross-verify our dataset with other similar lists to ensure that we do not miss anything that others have identified and we do not double count any cases.

We would like to highlight that, despite our best efforts, there is a high possibility that a significant number of distress deaths go unrecorded. There are at least three reasons for this. First, unlike the cases of COVID-19 infections, there is no system of official recording of distress deaths. Secondly, not every death –– particularly of poor people dying in remote villages –– is reported in the media. Apart from the fact that media might not give space to every single death, coverage might also be low because, under lockdown, the reach of the media has become restricted. Thirdly, of what is covered in the media, bulk of the reports are in vernacular press. Among the various people and groups that are tracking these news, we have been able to cover English, Hindi, Tamil, Kannada, Telugu, Malayalam and Gujarati press, but are unable to cover many others. Also even when somebody among us can read a particular language, we cannot rule out the possibility that, despite all the efforts, some reports are missed. It must also be noted that there is sometimes a lag in the reporting of these deaths and our finding these reports. As a result, the problem of under-counting is somewhat accentuated in the most recent data and the data for the most recent days should be interpreted with extra caution. Finally, some cases of suicides and deaths, although related to the lockdown, may not be reported as such. Unless the report specifically draws the connection with COVID and lockdown-related issues, we do not include it in the database. This may result in exclusion of some cases.

An additional risk comes from the distortion of reporting across media sources: in some cases, details including names, dates and ages related to the same incident are reported differently in different reports creating the possibility of double counting. Avoiding such errors is a challenge and requires special care.

In addition to our dataset on distress deaths, the article uses data on infection deaths from the India COVID-19 Tracker website (https://www.covid19india.org). Official data on number of deaths due to COVID-19 infections are provided in daily bulletins released by the Ministry of Health and Family Welfare. COVID-19 Tracker website combines these with State-level information, which is usually more update and more detailed. The team working for this website compiles all the information and verifies it.

It is worth mentioning that the data on infection deaths could also be somewhat understated if all people dying with flu-like symptoms are not tested for COVID-19 infection. A majority of infection deaths take place because of co-morbidity (other diseases such as diabetes or hypertension becoming aggravated because of COVID infection). It is therefore possible that deaths of some people with other sicknesses, along with flu-like symptoms, are recorded as deaths because of other problems (say, heart failure) without them being tested for COVID-19 infections. While lack of testing may cause some under-reporting, the extent of under-reporting in data on deaths is likely to be less than in the data on COVID-19 infections. This is because people with critical illnesses are more likely to go to hospitals, and if they go to hospitals in a critical situation with flu-like symptoms, than period with mild symptoms. As a result, the chances of getting tested would be higher for people with critical illnesses.

What do the data show?

Infection deaths and distress deaths

The most important finding from these data is that the total number of COVID-related deaths are not merely deaths due to infection but are also due to distress resulting from the manner in which the lockdown was implemented. And these distress deaths are not a small number and even though both infection and distress deaths may be understated, these make the total number of deaths significantly higher.

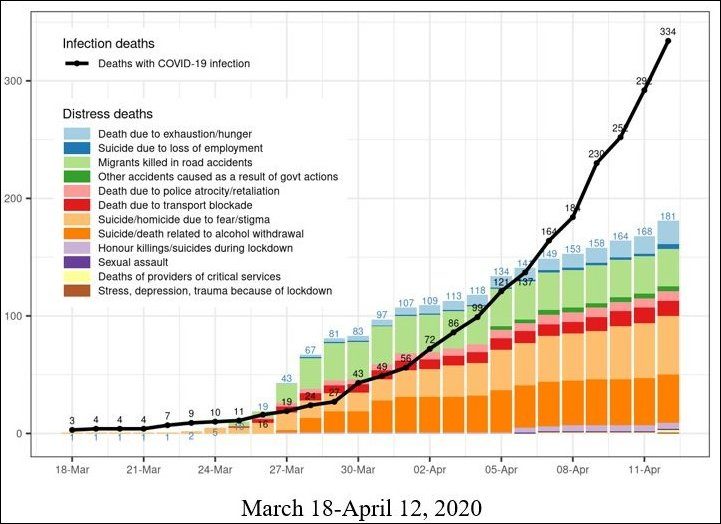

As per the information available at the time of writing this article, the total number of recorded deaths associated with the COVID-19 pandemic in India was 515. Of these, 334 were infection deaths while 181 were distress deaths. Imposition of a prolonged lockdown without planning has resulted in loss of livelihoods for a vast number of people and created a whole range of other problems which had not been thought about despite the fact that India had several months of time to prepare to deal with the pandemic. In terms of recorded data, the number of distress deaths were higher than number of infection deaths until April 6th after which the infection deaths have tended to increase faster than the distress deaths.

Figure 1: Number of infection deaths and distress deaths during

COVID-19 pandemic, India, March 18-April 12, 2020

What is the nature of this distress?

While some infection deaths may be unavoidable, distress deaths are preventable. The fact that the mitigation strategy, and in particular the extended lockdown, suddenly robbed people of their livelihoods has been widely reported. While this has been a major cause of distress, and of many deaths, we would like to examine this more specifically. With this objective in mind, we have been trying to study these cases to understand the nature of distress. This has not been an easy task and over the last three weeks that we have been tracking the information, we had to define new categories to capture emerging features of these deaths. What did we get to learn from this exercise?

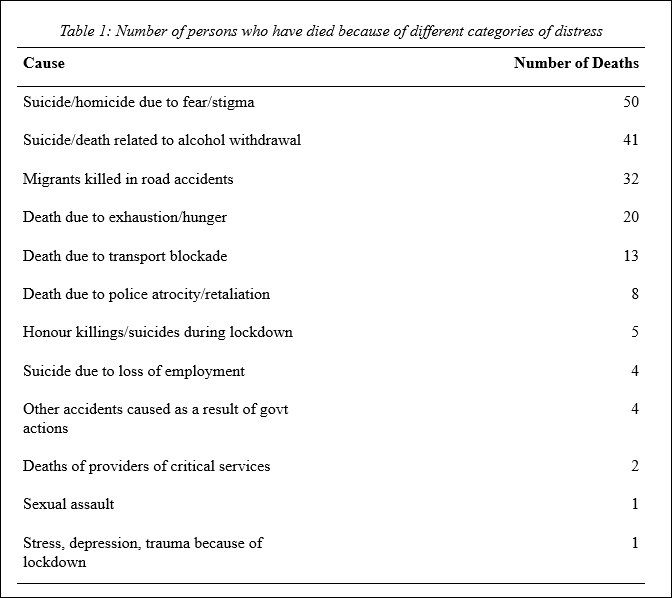

The most significant cause of distress deaths so far has been the fear of the disease or stigma associated with the COVID infections. A large number of people who were suspected of infections committed suicide, died in attempts to escape from miserable conditions in which they were quarantined, or killed somebody in an attempt to escape. Out of 181 distress deaths recorded until the time of writing, 50 were attributable to such reasons. Between March 27 and March 30, when the massive exodus of informal workers happened from cities towards their native villages, a number of them were run over by trucks and other vehicles carrying essential supplies. We have recorded 32 such deaths. In Telangana, Tamil Nadu, Karnataka and Kerala, a number of cases have been reported of alcoholics dying because of consuming various poisonous chemicals and concotions because of inability to get alcohol. We have recorded 41 such deaths.

A number of migrants died of exhaustion or hunger as they attempted to walk hundreds of kilometers to reach their villages. Even after the initial wave of migrants subsided after the first week of lockdown, the deaths due to hunger have continued to rise steadily. At the time of writing this piece, a total of 20 persons were recorded to have died because of hunger or exhaustion. This includes the report, which came as we were writing this article, of 5 children who were thrown into the river by their mother because she could not feed them.

There has also been a steady rise in deaths because of police atrocities (8 in total) and transport restrictions (13). Transport restrictions have resulted in, most importantly, deaths of patients who were unable to reach hospitals as well as suicides by farmers unable to transport their produce to the market.

The fact that there are so many different causes of deaths is noteworthy. The impact of lockdown and restrictions has been extremely differential across classes, castes and gender. This is also seen starkly in the data on deaths. There was a recorded killing of a person who had fled his village after inter-caste marriage to save his live but was forced to return to the village because of the lockdown. Young people in love have committed suicides because they were unable to escape the wrath of their families because of the lockdown. Women in isolation have been killed or forced to commit suicide because of sexual assaults. A sanitation worker died while fumigating the streets because the local administration did not think it necessary to provide the person with mask and other safety equipment. A police sub-inspector committed suicide because of the prolonged stress caused by imposing the lockdown.

The dark green colour in Figure 1 refers to deaths due to accidents caused as a result of government actions. This category came into being on April 5th when an old woman and two girls died in a village in Munger because their hut caught fire thanks to lighting of lamps at 9 pm in response to the call by the Prime Minister to do so.

Who were the people who lost their lives because of the lockdown?

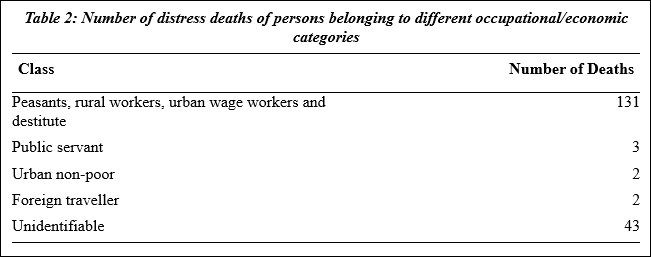

It has been widely discussed that the viral infection is, by and large, class and gender blind. This, however, is not true of the distress that has been caused by the lockdown. Our data clearly show that a vast majority of distress deaths were from among the poor, marginalised and vulnerable sections of the society.

While most news reports do not provide a lot of details of the deceased person for us to be able to identify class/economic status of the person very well, in a large number of reports, there is some information that broadly indicates the economic/vulnerability status of the deceased. Of all the reported deaths, we could not decipher the economic/vulnerability status of the deceased person in 43 cases. Most of these were unidentified alcoholics. There were also a few others, for example patients who died because of inability to reach hospitals, where the report contained no information that would allow us to decipher the status of the deceased. Since the news reports do not provide adequate information for these cases, we have classified them as unidentifiable.

Even in cases where some information was available in the news reports, we are able to do only a very broad characterisation. Of these cases, 131 were identifiable as peasants, rural workers, urban manual workers or destitutes. The potentially non-poor cases that are discernible include two public servants, two persons who lived in apartments in large cities and were therefore unlikely to be poor, and two foreign travellers.

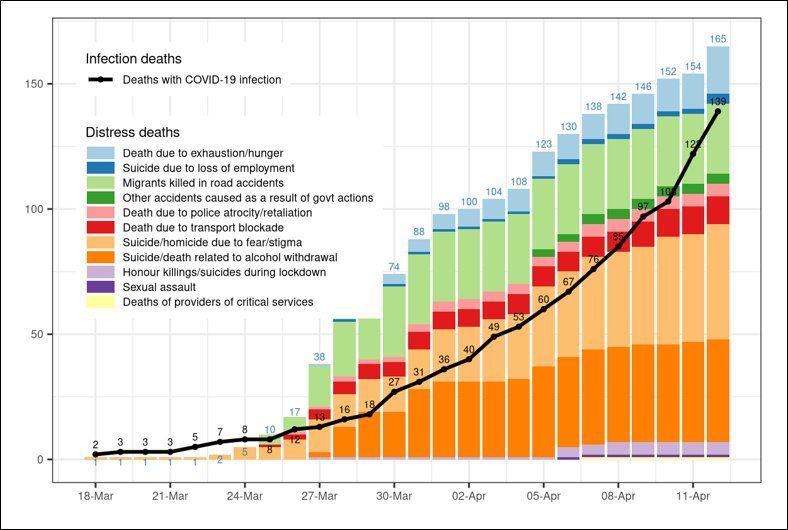

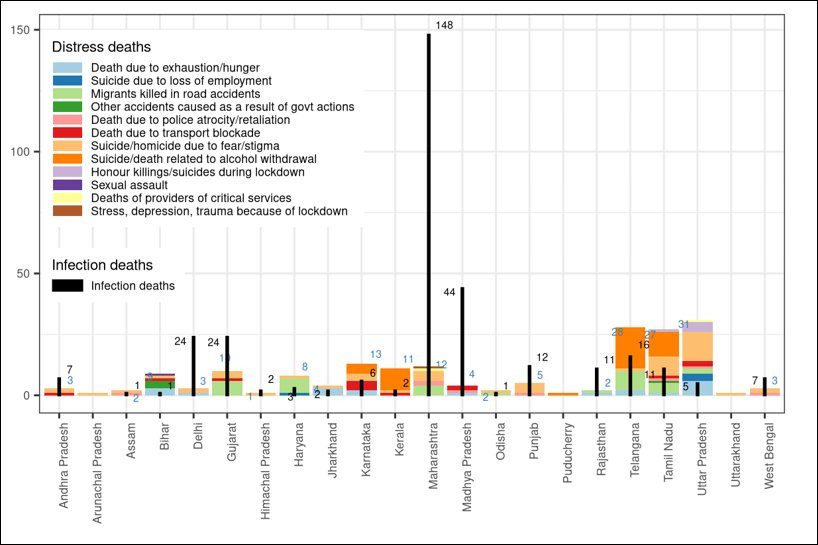

It is also noteworthy that, while infection deaths have been concentrated in a few large cities, distress deaths have taken place all over the country and have been concentrated in smaller cities, towns and villages. If one excludes Maharashtra, where a large number of infection deaths have taken place in a few major cities, and Madhya Pradesh, where a number of infection deaths have taken place in Indore, one finds that the recorded distress deaths far outweigh the infection deaths (Figure 2). The strategy of lockdown may be effective in ensuring physical distancing and isolation in better-off parts of the hotspot cities, the lockdown is not sufficient to ensure physical distancing in cramped slums in these cities. At the same time, large parts of rural India are clearly faced with this continually unfolding socio-economic crisis threatening their lives.

Figure 3 shows that infection deaths are high in a few states with hotspot cities such as Maharashtra (such as Mumbai and Pune), Madhya Pradesh (Indore), and Delhi. At the time of writing this article, distress deaths are much higher than infection deaths in Assam, Bihar, Haryana, Jharkhand, Karnataka, Kerala, Odisha, Tamilnadu, Telangana, and Uttar Pradesh. While there are no infection deaths in Arunachal Pradesh and Uttarakhand, distress deaths have been reported. While there is a big question mark on how effective this haphazard response to COVID-19 is in containing infection deaths, there is no doubt that the distress has spread very widely and very fast.

Figure 2: Number of distress and infection deaths in States and UTs other

than Maharashtra and Madhya Pradesh, March 18-April 12, 2020

Source: See https://coronapolicyimpact.org for the data on deaths of COVID-negative persons

and https://www.covid19india.org for the data on deaths of COVID-positive persons.

Figure 3: Number of distress and infection deaths, by States and UTs, April 12, 2020

Source: See https://coronapolicyimpact.org for the data on deaths of COVID-negative persons

and https://www.covid19india.org for the data on deaths of COVID-positive persons.

Why is this important?

It has been widely discussed that a highly infectious disease of this kind spreads exponentially, at least until a vast majority of people are already infected and re-infections do not take place in a major way. This results in a very fast, and continuously accelerating, spread of the disease. However, what has not been widely recognised is that, unless effective public action is taken to control it, economic distress and mortality due to loss of livelihoods, and the vicious cycle that it can create, can also compound the deaths caused by the pandemic. There are at least two reasons why additional mortality because of economic distress is likely to compound over time. First, the economic factors feed into each other, and this can create a compounding effect. Secondly, while people having a certain level of distress can tolerate it for some time, as distress accumulates, they would lose this ability. A person can go hungry for a few days, but as undernourishment accumulates, it could reach a point where the person succumbs to the lack of adequate dietary energy. While the most vulnerable and most acutely food insecure would be the earliest victims of such distress, over time, the distress could intensify for a much larger population of persons which started with moderate levels of vulnerability. It is therefore important to dispel the misconception that while the mortality due to COVID-19 infections grows exponentially, the mortality due to economic distress is likely to either flatten out or at most rise linearly.

We are not trying to understate the risk of very high mortality because of COVID-19 infections. We are trying to emphasise that, unless effective measures are taken to control the distress and mortality due to factors other than the viral infections, the overall level of mortality could rise at an exponential rate much higher than the rate of growth of COVID-19 infections.

Various experts and public figures have recommended that dealing with this crisis requires a massive expansion of social protection including large-scale cash transfers, universal distribution of free foodgrains, payment of unemployment allowance to NREGA job card holders, increased public spending, to reduce this distress. By providing a measure of the socio-economic distress caused by the unpreparedness and unplanned lockdown, this article highlights the criticality of the need to undertake such measures without delay. Not only is this distress set to intensify in the weeks to come, the nature of distress is changing and unfolding with time. While road accidents claimed many lives of migrants in the early days of the lockdown, hunger, loss of employment, sexual assaults, fear and stigma have seen a steady rise. With the extenstion of the lockdown, and with no signs of the social protection measures being on the anvil at the scale that this crisis warrants, a more complex socio-economic crisis is set to unfold.

There is also a great need to systematically record incidents of distress. While the lockdown has incapacitated academic scholars and social activists from venturing out for fieldwork, this responsibility lies squarely on the news media. We hope our observations would throw light on the the historic responsibility the news media ought to bear on its shoulders at this time.