NATO geopolitical strategy has now joined the ‘coalition’ of Western geoeconomic forces accelerating planetary heating,…

India’s BoP Story C. P. Chandrasekhar and Jayati Ghosh

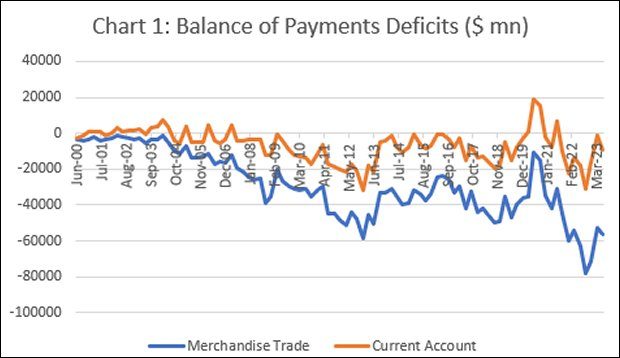

Unlike many low- and middle-income countries (LMICs), the Indian economy is not characterised by external debt stress or distress that could lead to default. It does record almost consistent current account deficits on the balance of payments, but these are not at unsustainable levels. They can be easily financed with ‘normal’ net capital inflows. Given the recent spate of external shocks affecting all countries, inflicted by the COVID pandemic and speculative increases in global oil and food prices, this is surprising. This is especially so, because India is not among the developing countries that have successfully diversified into manufacturing exports that would enable it to benefit from a return to post-pandemic normalcy. Nor is it free from dependence on imported oil, the prices of which have been downward sticky, even if volatile, in recent times. India also has a penchant to import and hoard large volumes of gold. The result has been that India has recorded consistently high and worsening merchandise trade deficits (Chart 1).

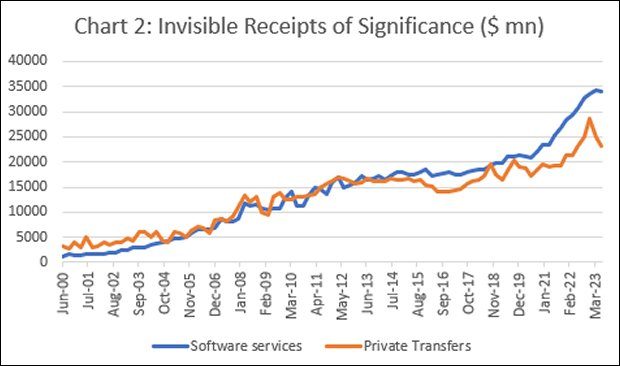

If the chronic and rising trade deficits did not lead to balance of payments difficulties and debt distress, it was because the distance between the absolute values of the trade and current account deficits widened, with the current account deficit remaining low and even turning positive in some years. Underlying this difference between the two deficits was the net positive receipts of foreign exchange from two forms of labour exports by India. One was the receipts from cross-border provision of software (labour) services through digital means. The other was implicit receipts from the export of labour services in the form of the transfer of their savings by migrant workers located abroad and engaged in activities varying from construction to accounting and health and education. As Chart 2 shows, net receipts from both exports of Software Services exports and Private Transfers (remittances) rose continuously, and almost in tandem.

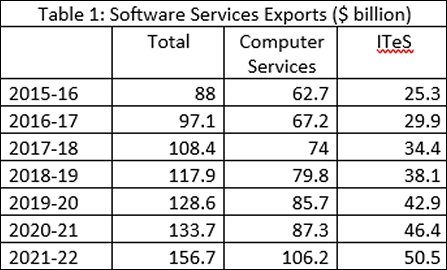

The reason why we can treat foreign exchange inflows from cross-border supply of software services as representing receipts from export of labour, is because of the nature of the software services exported. As Table 1 shows, computer services have dominated total software services exports (remaining close to 70 per cent of the total), with the balance being accounted for by business services, which include digitally delivered backroom services and call centre activities such as customer care services. These were the main sources of software services export revenues. On the other hand, software product development provided an extremely small component of the software services exported, falling from 4 to 3 per cent of the total.

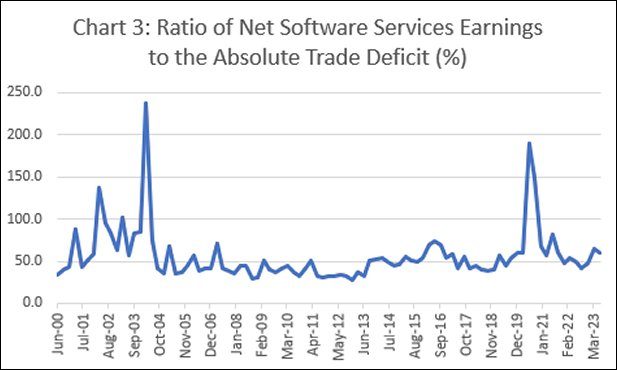

The contribution of these software services export earnings to neutralising the deficit in merchandise trade was substantial, amounting to around 50 per cent of the total in most years (Chart 3). Add on an equal contribution from remittances from workers abroad, and the deficit in merchandise trade was more or less fully covered. Thus, despite India’s failure to emerge as a major exporter of manufactures in a transforming world economy, its ability to export cheap labour services of different kinds in multiple ways endowed it with a kind of resilience on the external front. It helped finance the cost of a range of foreign exchange expenditures in the current account, from imports of goods and services to payments to foreign investors and creditors. The deficit remaining to be financed with capital inflows was, therefore, relatively small.

Interestingly, the resilience delivered by these unusual sources has provided the basis for the emergence of a different kind of external vulnerability or fragility. India’s relatively strong current account position has made it an attractive destination for foreign financial investors, who appear to be convinced that the risks of default, expropriation or currency depreciation are much less in India than in other low and middle income country markets. The result has been a large inflow of financial capital, far in excess of the country’s current account financing needs, which, as argued above, have remained low. This excess capital, not being needed immediately to finance foreign exchange expenditures, has contributed to the build-up of India’s foreign exchange reserves, which fluctuate around the $600 billion level (equivalent to the value of 11 months’ worth of imports). This figure is often cited to flag the strength of India’s external sector and economy. These high reserves also dampen fears of any large currency depreciation and lower foreign exchange risk in the perception of foreign investors, encouraging more capital inflows and keeping reserve levels high or raising them even further.

But the counterpart of this accumulation of reserves is an Increase in India’s foreign exchange liabilities, since there are no large current account surpluses that help earn these reserves. They merely reflect the excess inflow of capital of a kind that add to the country’s foreign exchange liabilities. The ‘costs’ of those inflows, in the form of repatriated profits and interest for example, have to be serviced in foreign exchange, and the liabilities themselves have to be settled in foreign currency. Since these liabilities are the result of inflows of ‘footloose’ capital, they could exit at short notice. India could in principle experience a sudden and large outflow of capital resulting from a collapse of foreign investor confidence, often for inexplicable reasons.

In sum, foreign exchange receipts from exports of software services, which help strengthen India’s external position and increase its resilience can, ironically, trigger a process that increase the country’s fragility. This is India’s own version of the Dutch disease. What policy should focus on is earning through exports the foreign exchange reserves needed to cover around 3-6 months of imports, rather than trying to keep capital flows high enough to sustain and raise the level of reserves.

(This article was originally published in the Business Line on October 2, 2023)