The Trump administration’s decision to terminate 90% of USAID’s foreign aid contracts in February 2025…

Climate Finance: The IMF’s stance C. P. Chandrasekhar and Jayati Ghosh

Early October provided yet more evidence of the breakdown of multilateralism and the lack of international commitment from countries, to work together to address shared national challenges. The 2023 pledging Conference for the second replenishment of the Green Climate Fund, the largest climate-dedicated multilateral funding source, generated only $9.3 billion of commitments from 24 countries. That is lower than $10.3 billion pledged by 45 countries when the fund was created in 2014, and $10 billion committed by 32 countries during the first replenishment in 2019. This failure to mobilise even a nominally higher sum for the second replenishment for the conference is telling.

Soon thereafter, the fourth meeting of the Loss and Damage (L&D) Transitional Committee (responsible for arriving at recommendations on how to address L&D and for deciding on the form of a special fund for the purpose approved at the COP27 climate summit) failed to arrive at a consensus. This was supposed to generate recommendations to be discussed and, possibly, ratified, at COP28. Another meeting is now planned to be held in early November, just ahead of COP 28, to somehow get a consensus.

These developments should not surprise us. After all, even the promised (meagre) amount of $100 billion a year of climate finance from the developed to the less developed by 2020 is yet to be achieved, even in nominal terms. Of this, the only component that comes through a transparent multilateral channel in which developing countries have a say—the UN’s Green Climate Fund—is only 10 per cent. And even that small sum cannot be mobilised in time.

The report of Working Group III in the most recent sixth assessment of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (WGIII6AR of the IPCC) places the cumulative share of North America, Europe, Japan, Australia, and New Zealand in anthropogenic carbon emissions at 43 per cent. Add on Eastern Asia, which includes China, and that share rises to 55 per cent. Calling on all countries to contribute to mitigation and adaptation purely on the basis of their own resources is obviously unfair. Developed countries need to finance much of the effort at reining in carbon emissions and global warming.

Failures on this front are sought to be justified on the grounds that there is only so much that rich country governments can do, given the fiscal constraints they face. So, the ‘global’ (rather than rich country) failure is attributed to an inability to persuade private capital to invest in projects that mitigate carbon emissions and help countries adapt to the impacts of ongoing climate change. That absolves the developed countries of their historical responsibility, despite their disproportionate share of cumulative carbon emissions.

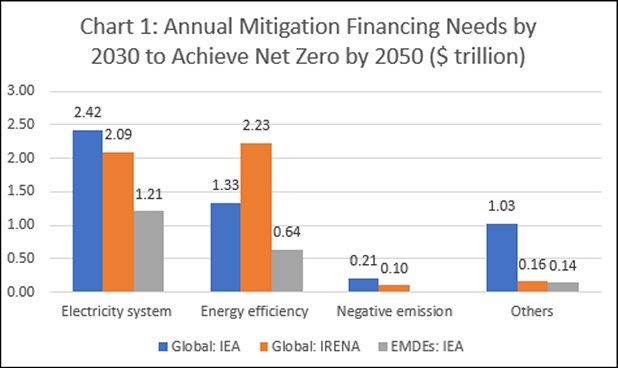

The latest salvo in this propaganda war comes from the IMF, in chapter 3 of its Global Financial Stability report (GFSR) of October 2023. The report estimates global financing needs for mitigation needed to achieve net-zero emissions by 2050, using data from the International Energy Agency (IEA) and the International Renewal Energy Agency (IRENA). That ranges from $4.5 trillion to $5 trillion a year (adjusted for inflation and in 2020 US dollars) (Chart 1). The IMF estimates that around 60-70 per cent of that needs to be directed to the energy sector. This excludes the large expenditures required for Adaptation and dealing with Loss and Damage.

The IMF uses IEA data to estimate the financing for mitigation required in the Emerging Markets and Developing Economies (EMDEs) at $2 trillion a year, or around 40-45 per cent of the total. By contrast, the WGIII6AR observed that the IEA suggested that as much as two-thirds of future collective climate investments would have to occur in developing countries, making cross-border financial flows crucial.

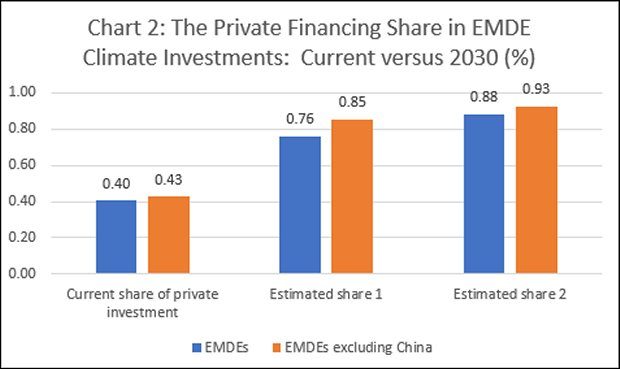

Particularly striking is the IMF’s estimate that the share of private financing in climate investments would have to rise from 40 per cent currently to 76-88 per cent by 2030. This includes China, where the share of public funding would be overwhelming larger than elsewhere in the EMDEs. Excluding China, the private financing share has to rise from 43 per cent currently to between 85 and 93 per cent (Chart 2)! The public sector is to have only a minimal role, even allowing for the share of climate investments in total public investment increasing by 1.5 times from current levels.

The IMF’s case for this extremely high private share is based on two arguments. First, country-by-country gross investment projections suggest that growth in total public investment would be woefully short of what are needed for climate investments. Second, while carbon pricing “can be highly effective in shifting private capital flows to low-emissions investments”, it may be politically challenging to implement.

The first argument must be based on assumptions regarding the extent to which additional public resources can be raised by enhanced taxation of income and wealth of the world’s richest, and international coordinated taxation of the profits of transnational firms and fair sharing of the resultant proceeds. Thus far, the IMF has consistently avoided recommending such policies to the EMDEs and in fact emphasized fiscal conservatism when it comes to expenditures and budgetary deficits, amounting to severe austerity in most cases. This inevitably creates a large potential role for private finance, since “the private sector share of climate finance is calculated as the residual of climate investment needs not covered by the public sector.”

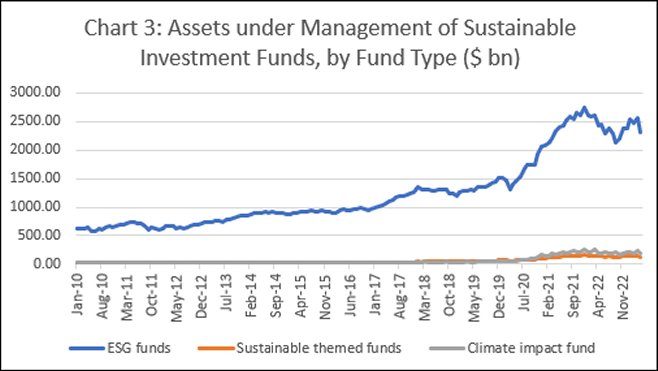

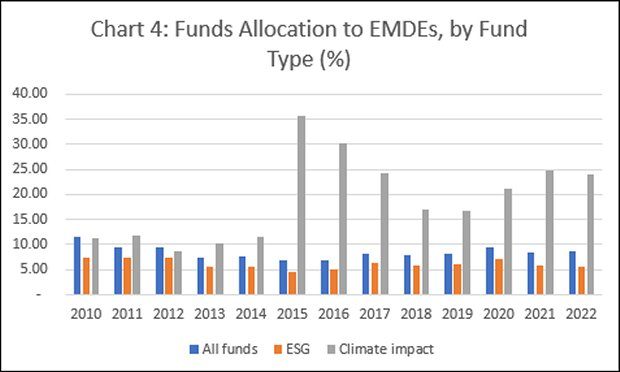

The IMF, however, ignores the extremely low probability of private investment stepping in to “fulfil its role”, even though its own estimates suggest this. As of April 2023, assets under the management of the so-called “sustainable investment funds” (SIFs) amounted $2.6 trillion, of which only around 9 per cent (or $250 billion) were allocated to the EMDEs in 2022 (Charts 3 and 4). The IMF projects that mitigation-related investments must rise to $2 trillion by 2030, with the private share as much as $1.8 trillion. Assuming that SIFs must account for half of this investment, the flow to the EMDEs must rise fourfold within the next seven years. Why private investors would allocate such a large share of capital to low-return and high-risk climate investments is by no means clear. The IMF’s case is that such investments must be de-risked and incentivized with public funds. But with currently low public climate funding, even a large chunk of it would not whet the appetite of yield-hungry investors.

In any case, the evidence is clear that so-called SIFs very often make claims with regard to sustainability that don’t hold on verification. Around 88 per cent of the SIF funds under management are Environmental, Social and Governance (ESG) funds, which have been critiqued for not delivering on their claimed objectives. As Tariq Fancy (formerly BlackRock Inc.’s chief investment officer for sustainable investing) argues, the ESG movement is “a deadly distraction”, holding back on needed state action and regulation in the misguided belief that an ethical corner of the market would address the current climate, environment and social crises.

Seen in this light, the IMF’s case for a hugely enhanced role for private finance is nothing more than a cynical apology for the failure of rich polluters to pay for the damage they have and will continue to cause.

(This article was originally published in the Business Line on October 30, 2023)