Donald Trump’s top economic advisor claims the President has weaponised tariffs to ‘persuade’ other nations…

The Recurring Crisis: Debt in the LICs C. P. Chandrasekhar and Jayati Ghosh

Severe external debt stress in several low- and medium-income countries (LMICs) has raised two questions. The first is whether we are on a trajectory that would result in a generalised debt crisis of the kind that preceded debt write-offs under the Heavily Indebted Poor Countries (HIPC) Initiative of 1996 and the complementary Multilateral Debt Relief Initiative (MDRI) of 2005. The second is that, if the less developed countries are once again vulnerable, what needs to be targeted in current restructuring efforts to prevent such recurrence in the future.

In addressing these questions, it is necessary to step back from the tendency to conflate domestic and external debt. Recent restructuring efforts under IMF auspices have shifted focus from managing and preventing unsustainable levels of external debt to reducing the size of aggregate public debt (domestic and external). That shift has also resulted in an exclusive focus on sovereign debt, with little attention paid to the external debt being accumulated post-liberalisation by the private sector, which in the case of the LMICs as a group, amounts to more than a third of outstanding external debt stocks.

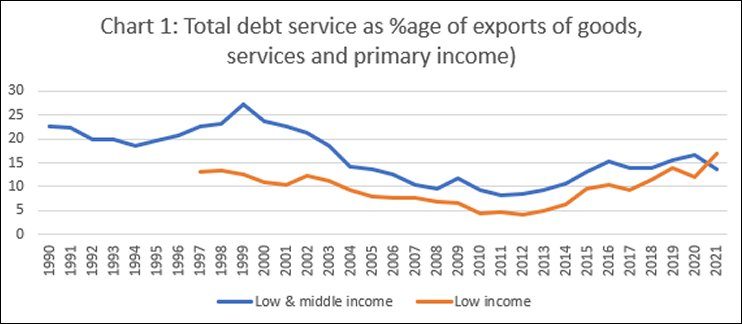

Debt stress arises when, after paying for imports, foreign exchange receipts from exports of goods and services and primary income prove inadequate to comfortably meet service payments (interest and amortisation) on accumulated external, foreign currency debt, which can only be serviced in foreign exchange. However, if we examine the evidence on the trend in the ratio of total debt service to receipts from exports of goods and services and primary income in the more than three decades since 1990, there is a marked difference between the LMICs as a group and the subset of low-income countries (LICs). In the former, the LMICs, after rising to a peak of 27 per cent in 1999, the ratio declined sharply to 8.6 per cent in 2011, and though it has risen since, it was, at 13.8 per cent in 2021, well below the levels in the 1990s (Chart 1).

This decline in the ratio for the LMICs, during the first decade of the present millennium, is largely the result of two factors. One was the substantial increase in export revenues that accrued to many less developed countries because of the commodity price boom, or the so-called “commodity supercycle”, which lasted through much of the first decade, especially over 2003-2007. The second was the fall in debt service requirements because of the debt restructuring and forgiveness that resulted from the HIPC and MDR initiatives, which benefited eligible low-income countries. One consequence of these initiatives was that in the years after 2009, when the commodity price boom was losing momentum, the decline in the debt service to export receipts ratio of the LMICs was largely on account of the decline in that ratio in the case of the LICs, as Chart 1 reveals.

What is noteworthy, however, is that after 2011, when the debt service ratio for the LMICs rose from 8.2 per cent to 16.8 per cent in 2020, much of the increase was on account of the increase in that ratio from 4.7 per cent to 12.1 per in the LICs. In fact, the figure rose further to 16.8 per cent for the LICs in 2021, while falling in the case of the LMICs as a group. Worsening debt service conditions in the LICs drove the total in this period.

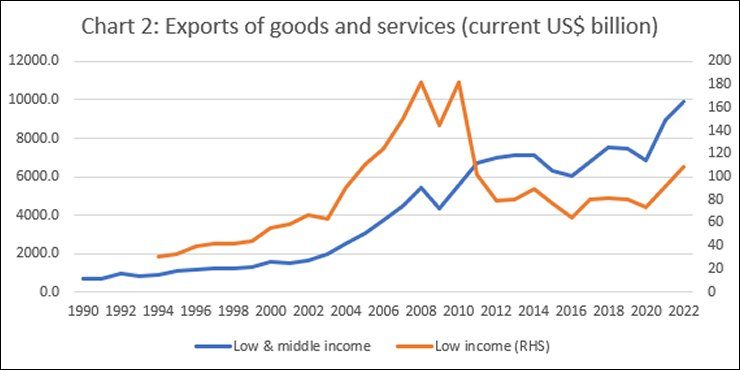

The reason for the differential performance of the LMICs and the LICs, after the effects of the debt relief initiatives had petered out, was the differential export performance between the middle-income countries and the LICs, leading to the differential in performance of the two overlapping groups of LMICs and LICs. (In addition, LICs also tended to contract debt from private markets on more expensive terms, because of the higher “risk premium”.) As Chart 2 shows, while receipts from exports of goods and services (excluding primary income) in the case of the LMICs rose consistently after 2003, in the case of the LICs that rise ended after the commodity price spike of 2003-2008, falling sharply by 2012 and remaining at a relatively low level.

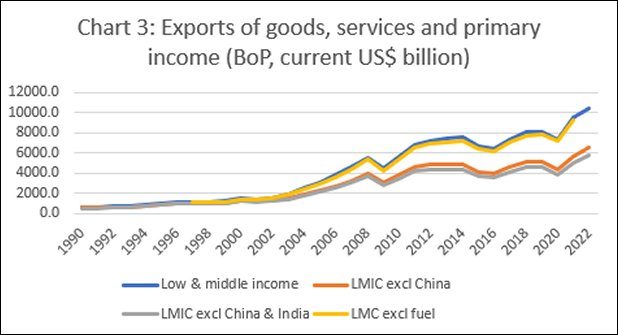

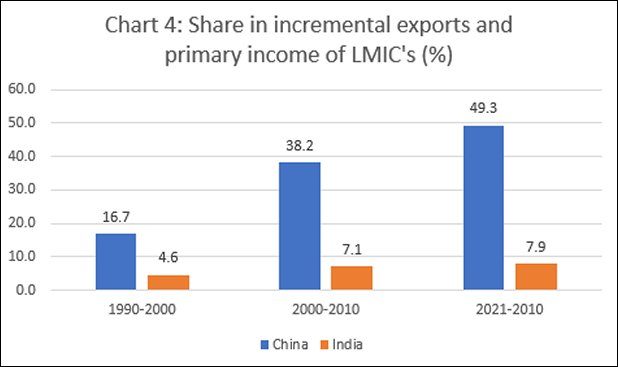

This, however, leaves unanswered the question as to why, not just many LICs, but a number of LMICs are debt stressed, and some such as Sri Lanka have also defaulted on debt. This apparent puzzle is not difficult to resolve, once we take into account the exceptional export performance of China, and to a much smaller extent India. As is revealed in Chart 3, if we separate China from the total, much of the post-2008 rise in the receipts from exports and primary income of the LMICs was on account of the increase in those receipts for China. Excluding India or the receipts from fuel exports does not make much difference, on the other hand, partly because India was not an exceptional exporter and the main fuel exporters are high income countries. Over the three time periods 1990-2000, 2000-2010 and 2010-2021, China accounted for 17, 38 and 49 per cent respectively of the increments in receipts from exports and primary income of the LMICs (Chart 4). After the commodity boom of the 2000s, many LMICs did not garner enough foreign exchange receipts from exports and primary income that would have allowed them to service their debts comfortably. When their foreign exchange receipts fell sharply during the COVID-19 pandemic, because of the collapse in exports, tourism revenues and remittances, and their foreign exchange expenditures spiked due to increases in the global prices of fuel and food, the burden of debt service intensified, leading to default in some cases.

What this establishes is that resolving debt crises in a manner that prevents future recurrence requires addressing the inability of many less developed countries to expand export revenues and limit import spending, because the inadequacy of net export receipts leads to the unsustainable accumulation of external debt as well as a failure to meet debt service commitments when some threshold is crossed. This requires not just strengthening export capacities, but limiting and substituting imports with domestic production, as well as addressing the global inequalities and structural inadequacies that depress less-developed country exports and aggravate the debt burden.

Unfortunately, in current restructuring exercises, the only effort in this direction is the strategy to combine currency devaluation with liberalisation of foreign investment rules and increased multinational dependence to drive exports and limit imports. That strategy has repeatedly failed to boost exports, tends to increase the import intensity of domestic economic activity and lifts foreign exchange outflows on account of dividend and royalty payments and transfer pricing. Along with the push for fiscal consolidation, this contracts output, leading to a rise, rather than a fall, in the debt to GDP ratio. This strategy is unlikely to resolve the debt problems currently plaguing so many LMICs.

(This article was originally published in the Business Line on August 7, 2023)