Programme 8-9 am: Registration 9 – 10.30 am: Inaugural Session Chair and Welcome address: Dr.…

The Terrible Human Costs of Debt Service C. P. Chandrasekhar and Jayati Ghosh

The IMF’s estimates of debt stress suggest that as of May 2023, 11 countries were in debt distress (that is, in default or on the verge of default) while 51 countries were in severe moderate debt stress. Typically, a debtor country captures international headlines only when it actually defaults on some or all of its payments, or when it is forced to approach the G20’s Common Framework for a debt relief package, or when it appeals to the IMF for emergency liquidity support.

Yet this list of debt emergencies—or even the longer list of debt-stressed countries as estimated by the IMF—understates the actual impact of excessive debt in low and middle income countries. Far too many countries that are not classified as “debt-stressed” are so described because they are diligently keeping up with debt service payments, even at the cost of essential spending on their citizens and critical spending required to meet developmental and green transition goals.

There is a back story to this. Over the previous decade, most low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) that were previously excluded from private capital markets were encouraged to take on more loans, particularly via bond markets suddenly interested in more risky debt, because of persistently low interest rates in a world awash with liquidity. This was looked upon benignly by the International Monetary Fund and even celebrated at the World Economic Forum.

For many countries, this trajectory was unsustainable from the start. But recent events caused even governments that were deemed more ‘responsible’ to face repayment difficulties. All LMICs have faced forces beyond their control. The Covid-19 pandemic had major adverse impacts on economic activity, imports and exports, and foreign exchange earning capacity through tourism and remittances. The price hikes in global food and fuel markets since the onset of the war in Ukraine were temporary (and largely the result of corporate profiteering and financial speculation in commodity markets), but they nonetheless had severe and prolonged impacts on food prices in LMICs. Higher interest rates in the United States and the European Union caused globally mobile finance to flow back to those countries, creating a double whammy of depreciating currencies and reduced access to credit in the middle of debt cycles.

As a result, debt service payments on the legacy debt now have to be squeezed out of economies that are already in straightened macroeconomic conditions and are facing multiple other problems. Research by Matthew Martin with David Waddock provides some indication of what this has meant. Their study covers 144 countries, using data from various sources, including IMF and World Bank databases, as well as data on public budgets collected by Development Finance International. (All figures below are based on that study.)

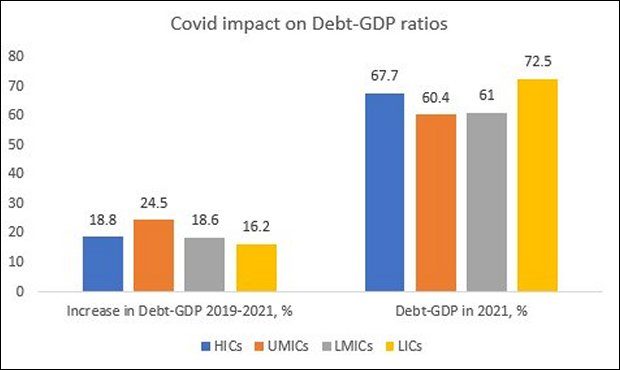

Figure 1

Figure 1 indicates the impact of the Covid-19 pandemic on public debt to GDP ratios by comparing 2021 with 2019. It is evident from Figure 1 that all countries increased their debt-GDP ratios during the pandemic; indeed, high income countries increased substantially because of the massive recovery packages many instituted, with significantly enhanced fiscal spending. But for the rich countries, particularly those with global reserve currencies, this debt was typically in their own currencies. By contrast, for other countries, a significant and often the greater part of public debt was in a foreign currency, with much of the debt being US dollar-denominated.

In lower middle and low income countries the increase in debt-GDP ratios during the pandemic was also significant, but less of it was because of new and additional fiscal spending; rather, it was often because of the moratorium on debt payments that allowed debt to accumulate without being paid for a period. As a consequence, by 2021, the debt-GDP ratio for high income countries had ballooned to 68 per cent mostly because of new fiscal spending, while the ratio for low income countries increased to an even higher 73 per cent mainly because of legacy debt.

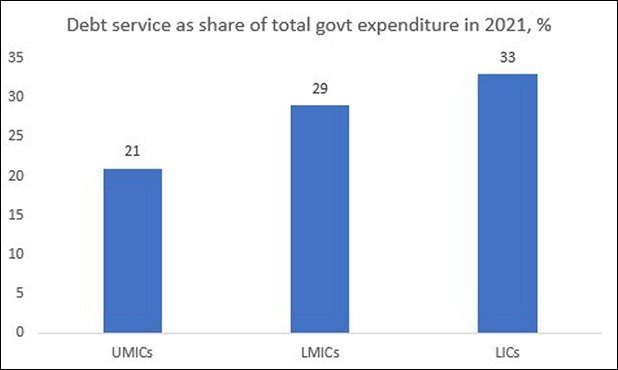

Figure 2

Governments in rich countries are also able to borrow at lower interest rates, and during this period the interest rates remained very low, often close to zero. Again by contrast, low and middle income countries have to pay a premium over prevailing global rates because of higher “risk perception”, with the result that the poorest and most vulnerable countries often have to pay the highest interest rates. In 2021, fully one-third of the public spending of the poorest countries was for debt service payments, while the ratio was only 21 per cent for the richest countries (Figure 2).

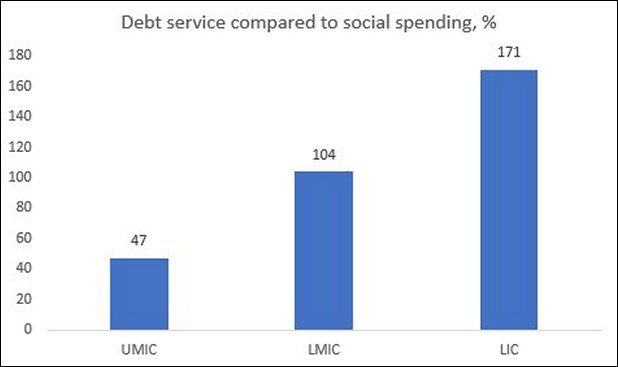

Figure 3

Figure 3 brings out what this meant in terms of meeting basic needs of citizens, by comparing debt service payments to core social spending (covering expenditure on education, health and social protection). In upper middle income countries, just under half of the amount of social spending was spent on debt service, but in lower middle income countries (where such spending is all the more required) the debt service payments were more than social spending. Shockingly, in the low income countries, debt service payments came to 171 per cent of social spending! Remember that these are not just the poorest countries, with significant proportions of absolutely hungry people, but also the most climate-vulnerable countries, which are already experiencing a range of climate-related shocks that affect ordinary people.

The belated and half-hearted measures at debt relief that have been on offer so far do little to resolve this problem. For example, apparently Sri Lanka and Zambia will continue to have to spend around 40 per cent of their budget on debt service after the supposed debt relief deals brokered by the IMF and the G20 Common Framework respectively.

This is not just a deeply unjust and unbalanced system, it is also completely unsustainable. The consequences for increased poverty and material downslide in affected countries are obvious; but these in turn will inevitably have terrible social and political consequences that cannot be “contained” within their own borders. The longer that international creditors (whether public or private) kick this can down the road, the worse it will be for them as well.

(This article was originally published in the Business Line on July 24, 2023)