Donald Trump’s tariffs have disrupted supply chains, roiled global markets, and escalated the trade war…

On the FDI Route to Manufacturing Success C. P. Chandrasekhar and Jayati Ghosh

By far the most significant ‘innovation’ in industrial policy under the current NDA government is the production linked incentive (PLI) scheme. It provides an incentive pay out or subsidy of 4-6 per cent of incremental sales based on domestic production. The focus is just on boosting production, since there are no domestic value addition or export sales requirements set. As Raghuram Rajan and his colleague have pointed out, using iPhone production as an example, this can encourage foreign firms to import components and equipment to assemble products here with little value addition. That seems to be okay in the government’s perspective, as long as investment and production rise. So, after an April 2020 launch restricted to the Large Scale Electronics Manufacturing sector, the scheme has been extend to cover 14 very diverse domains.

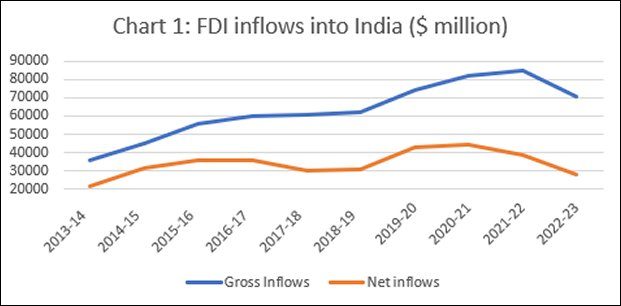

Though open to domestic players as well, by all accounts the scheme is targeted at attracting foreign investors. But the evidence on foreign direct investment shows little indication of the scheme having made a difference. Rather, as Chart 1 shows, since financial year 2021, gross FDI inflows lost momentum in 2021-22, rising by just 3.5 per cent as compared with 10.2 per cent in Covid year 2020-21. In 2022-23, gross inflows fell further, by 16 per cent. This does not suggest that the PLI scheme is working yet.

Even the modest rise in 2021-22 was possibly influenced by post-Covid acquisitions of shares in Indian conglomerates by global majors, such as the $20 billion stake purchase by Amazon in Reliance Industries, which was seeking to mobilise equity capital to reduce its huge debt. FDI inflow through the share acquisition route rose from $7 billion in 2020-21 to $14.1 billion in 2021-22, before settling back to $8.2 billion in 2022-23. Such inflows contribute little to building new manufacturing capacity.

Source: Reserve Bank of India Bulletin, Various Issues

Source: Reserve Bank of India Bulletin, Various Issues

The government, however, seems to be betting on the scheme having its impact with a lag. The Economic Survey presented in 2023, projected that the scheme will deliver investments of around Rs. 3 lakh crore over the following five years. But as of now, there is no cause for such optimism.

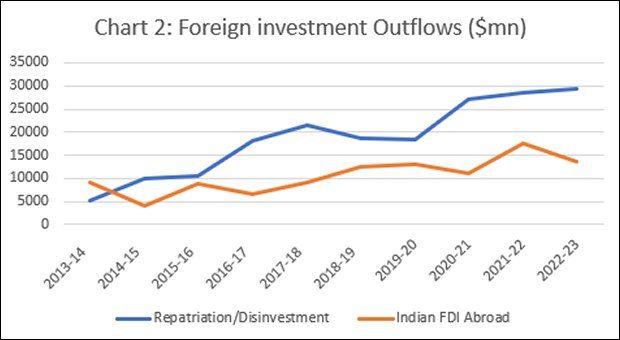

Another source of concern is that net FDI inflows, after taking account of repatriated investments and Indian investments abroad, have remained more or less flat and have been falling since 2020-21. This is because, even when gross inflows were rising, outflows were rising faster. Chart 2 disaggregates gross outflows into those on account of Indian FDI abroad and those due to repatriation of assets or disinvestment by existing foreign investors. While there has been some increase in investments abroad by residents from an average of $6.5 billion over 2014-2017, to $11.6 billion over 2017-20 and $14.1 billion over 2020-23, the corresponding figures for repatriation/disinvestment by foreign investors were $12.8 billion, $19.5 billion, and $28.3 billion. Clearly, there appears to have been a spike in the exit of foreign investors, rather than in new investment inflows.

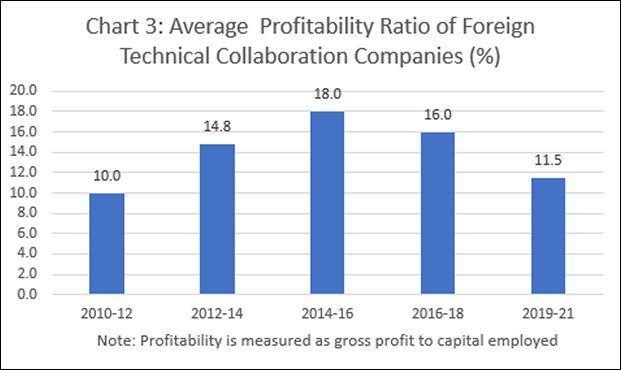

One factor explaining the decline in gross, and more significantly net, FDI inflows, is a declining trend in profitability, measured by the ratio of gross profit to capital employed. This is reported in the survey on firms that have entered into foreign technical collaborations and are substantially either foreign subsidiaries or ventures with a significant foreign stake. As Chart 3 shows, the average profitability ratio, having spiked from 10 per cent during 2010-12 to 14.8 per cent over 2012-14 and 18 per cent over 2014-16, fell to 16 per cent over 2016-18 and 11.5 per cent over 2019-21. The last of these also reflects the effects of the pandemic, but profitability stood at a lower 14.6 per cent even in 2019-20. We cannot make much of this trend, since it is based on profits reported by firms, which could be driven down by other factors, such as an increased resort to transfer pricing, for example. But the trend does point to a real decline that is not easily neutralised by the incentive on incremental sales.

The increased exit of foreign investment through the repatriation/disinvestment route also speaks to the nature of FDI in recent times. Conceptually, foreign direct investment, as opposed to portfolio investment, is considered to be investment motivated by long term interest that is substantially locked into fixed capital expenditures. Hence, it is considered far less ‘footloose’ that portfolio investments in equity. However, the statistical definition of FDI, is any investment from a single foreign source that acquires 10 per cent or more equity in a single domestic firm. It is known that there are foreign portfolio investors looking for short term capital gains buying more than 10 per cent equity in individual Indian firms. Such investments are, therefore, outlays by portfolio investors, who tend to book profits and exit within relatively short periods. The rise in outflows on account of repatriation/disinvestment possibly points to a rise in the share of such portfolio investments counted as FDI.

Source: RBI Survey on Foreign Collaboration in Indian Industry: 2019–2021

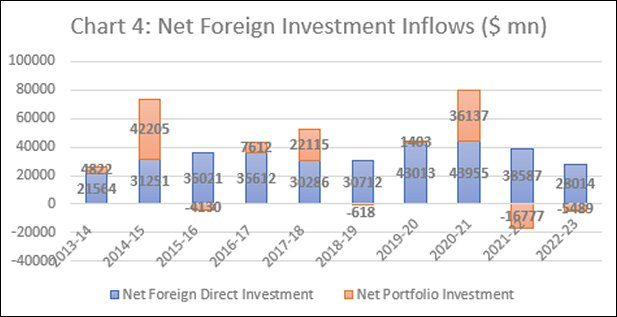

Figures on net foreign direct investment flows over time (Chart 4) indicate that this partial volatility in flows has on average resulted in stagnation. Net FDI flows averaged $34.3 billion during 2014-17, $34.7 billion over 2017-20 and $36.9 billion over 2020-23. This is problematic from a balance of payments point of view, since relative stable and rising FDI flows were seen as propping up total net inflows by compensating for volatility in portfolio flows. Net portfolio flows have indeed been extremely volatile over the last decade. More importantly, over 2021-22 and 2022-23, net outflows of portfolio investments have turned significantly negative, which combined with lower net FDI flows has resulted in a significant reduction of total net investment inflows into the country.

It is true that a small current account deficit, on account of large inflows of remittances and services export revenues, reduces India’s requirements of capital inflows to sustain the balance of payments. Nevertheless, this can become an area of concern. The government would do well to focus on this issue rather than on incentivising foreign investors in unproductive ways, in the name of boosting indigenous manufacturing.

(This article was originally published in the Business Line on June 12, 2023)