Programme 8-9 am: Registration 9 – 10.30 am: Inaugural Session Chair and Welcome address: Dr.…

Is India’s Rural Economy Diversifying? C. P. Chandrasekhar and Jayati Ghosh

Insufficient economic diversification, from low value added to higher value added activities, has been one of the important failures of the Indian development trajectory. Despite decades of relatively high growth of GDP, most of the work force remains trapped in low-value employment in agriculture and other primary activities, along with low-paying services. This pattern is unlike the successful late industrializers like Japan, South Korea and more recently China. The continuing preponderance of workers in primary activities in India is also unlike most middle-income countries at present. In the rural economy in particular, the slow pace of diversification has created an unstable and unviable situation as workers remain crowded into agriculture even as that sector show significant declines in share of GDP.

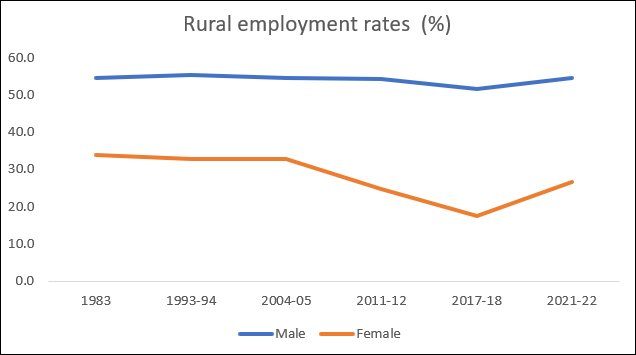

Figure 1

Source for all figures: NSSO Surveys of Employment and Unemployment and Periodic Labour Force Surveys, various issues

However, trends over the past two decades do point to some employment diversification, especially in rural India. Of course, this must be seen in the context of extremely low and even declining work participation rates for both men and women. Figure 1 shows how employment rates for rural males are not only very low by global standards and have remained broadly stagnant over four decades. For rural females, the trend is even more concerning—from the very low rate of only 34 per cent, the employment rate fell thereafter, collapsing to as low as 17.5 per cent in 2017-18. This severe fall in women’s recognized employment was responsible for the absolute decline in total employment over the period from 2011-12 to 2017-18. There was a slight recovery in the most recent period, 2021-22, although the rate was still less than 27 per cent, well below the rate of four decades earlier.

It is important to remember that these work participation rates do not capture all work, but only recognized employment, including self-employment. This excludes a very large amount of work performed in unpaid form by (mainly) women in the process of activities that ensure household consumption and survival. Such activities consist not just of unpaid care work within households, but also essential activities like fetching water and fuelwood, kitchen gardening, poultry raising etc. If such unpaid work is recognized (though it is not remunerated) more than 85 per cent of women in India are actively engaged in “economic” activity.

The work participation data for women are further muddied by the fact that a significant proportion of recognized women workers (around one-third in rural areas) are described as “unpaid helpers in family enterprises” – typically farms. Indeed, it is the shift in women in and out of recognized employment in agriculture that has been the most significant mover of employment changes in the past two decades. Other than this, employment has stagnated—a remarkable feature of an economy that has supposedly grown relatively fast.

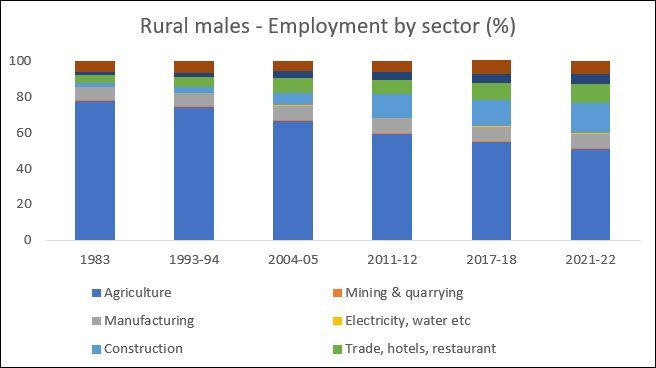

However, there have been changes in the structure of employment in these four decades, particularly for male workers. Figure 2 provides a sense of the sectoral changes in employment for rural male workers. There is a continuous decline in the share of agriculture from 77.5 per cent in 1983 to 51 per cent in 2021-22. However, the pace of the decline slowed considerably in the last decade. The biggest shift was to construction: more than half of declining share of agriculture is explained by the rise of construction as a major employer, which accounted for 16.6 per cent of rural male employment by 2021-22. Throughout this period, the share of manufacturing barely budged, remaining at 7-8 per cent, indicating the failure of rural industrialization to take off to any meaningful extent. Among services, trade hotels and restaurants more than doubled their share of male employment, and transport services also increased. But a significant proportion of these also remain relatively low-paying activities.

Figure 2

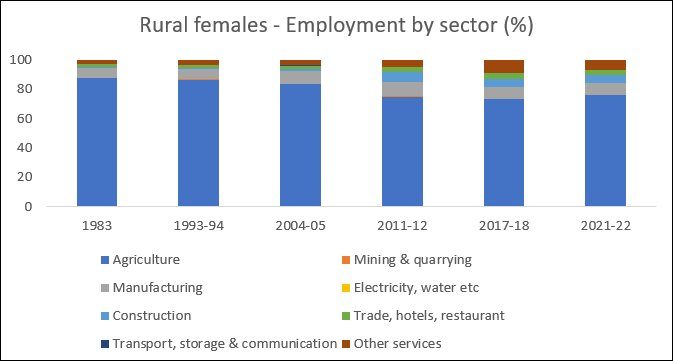

Figure 3

For rural females, even this limited diversification of employment was much less evident. The share of agriculture declined, but only from 87.5 per cent in 1983 to 73.2 per cent in 2017-18—and then remarkably showed a renewed increase in 2021-22 to 75.9 per cent. Manufacturing employment provided work for 6.4 per cent of rural women in 1983, and this increased to 9.8 per cent in 2011-12. But in the decade thereafter it declined once again, to account for only 7.9 per cent of rural women recognized workers in 2021-22. Construction increased significantly though it still accounted for only 5.3 per cent of rural female employment. Other services, mainly community and personal services, also showed substantial increases (from 2.8 per cent in 1983 to 8.9 per cent in 2017-18) but then declined again for the most recent period, to 6.8 per cent.

This suggests that the recent “revival” in the share of agriculture in women’s employment reflects the decline of other activities in terms of viable employment opportunities. Indeed, the increase in the share of women in agriculture is almost exactly equivalent to the declining shares of manufacturing, trade hotels and restaurants, and other services. Since the latter are better representations of the desired economic diversification, it is likely that some women were essentially forced back into being recorded as employed in agriculture because of lack of other options. Most of this is in the form of self-employment or unpaid help in family farms, since wage employment (whether regular or casual) is less likely to be a “refuge” sector.

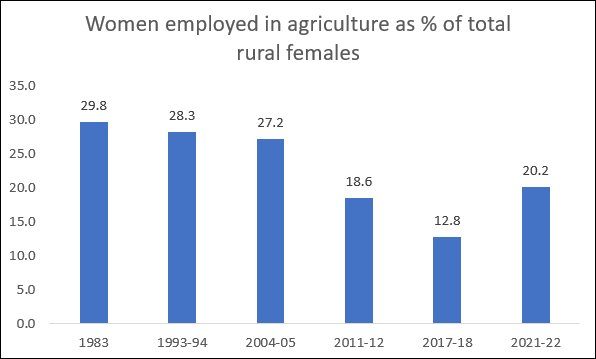

Figure 4

Even this, however, does not reflect any particular dynamism given the overall decline in women’s recognized work participation especially since 2004-05. Figure 4 presents the share of women employed in agriculture as a proportion of the total rural female population. This declined continuously over the decades, reaching only 12.8 per cent in 2017-18. The subsequent increase to 20.2 per cent in 2021-22 seems to be more of a distress move, as noted above, but even that remains well below the levels of earlier decades.

There are many reasons for this extremely uneven performance of economic diversification, both in general and particularly across gender. Some are structural and systemic, some reflect medium term processes (such as how the rural economy has fared over the period of economic globalization) and some reflect short term policies (such as the ill-fated demonetization of November 2016 and the imposition of GST in July 2017, both of which were major shocks for the rural economy). But overall they reflect a continuing failure of the development project, which policy makers can ill afford to ignore.

(This article was originally published in the Business Line on May 29, 2023)