Donald Trump’s tariffs have disrupted supply chains, roiled global markets, and escalated the trade war…

Social Protection for the Self-employed C. P. Chandrasekhar and Jayati Ghosh

The Covid-19 pandemic highlighted the urgent need for a universal social protection floor—something that has been talked about and even internationally accepted for more than a decade now, but has still received relatively little serious attention from policy makers in most countries. The challenge is to ensure basic levels of food, health, income and livelihood security, not only in periods of crisis like the pandemic or economic shocks but also in the “normal” course of economies and societies.

This has become a major concern because of the dramatically increased economic inequality and greater vulnerability of people to adverse events and processes, as well as the heightened fragility of material life. It has been compounded by the large (and growing) share of informal workers in almost all economies, which means that, even among those in some form of paid employment, there are few forms of legal protection or social security that they can automatically access in periods of difficulty.

While the problems of providing social protection for informal workers are obviously significant and varied, they are even more acute in the case of workers who are described as “self-employed”. For such workers, there are no declared employers who could be seen as even partly responsible for providing either legal or social protection

It is true that there is widespread prevalence of outsourcing of both goods and services, and an increasing tendency to label small producers of goods and services as “independent contractors”, even when they are effectively dependent on a particular company. This means that though there is some sort of employment relationship, this is effectively concealed, certainly for legal and policy purposes. Therefore even those who are tied to particular companies as suppliers do not have legal recourse and end up being responsible for their own remuneration, safety and other conditions at work, and social security.

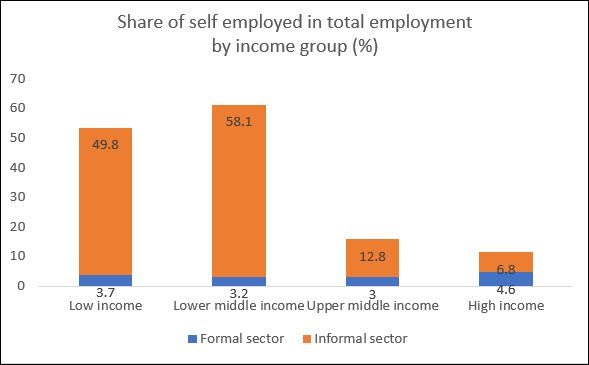

This is a much more extensive concern than is often realised. Figure 1 shows the proportion of self-employed workers to total (recognised) employment, disaggregated by per capita income group of countries. (These are based on ILO estimates made in 2019, using the most recent available data at the time.) It should be noted that even these are significant underestimates, because they exclude all those engaged in unpaid work, whether within households or in communities. Such workers are clearly no less deserving of social protection. In some countries (and especially in regions like South Asia) such unpaid workers, especially women, even constitute the dominant share of people of working age, even though they are typically classified as “not in the labour force”.

As evident from Figure 1, in low and lower middle income countries, self-employed workers are more than half of recognised workers. In lower middle income countries, they constitute nearly two-thirds of employment. A very small share of such workers are those working in the formal sector, although this proportion is much higher among all self-employed workers in upper middle and high income countries.

Figure 1

Source for all figures: ILO 2019, https://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/—dgreports/—dcomm/—publ/documents/publication/wcms_723282.pdf accessed on 7 January 2023

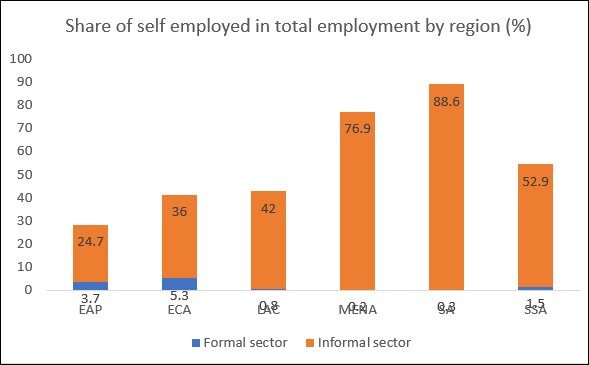

The fact that lower middle income countries show such a high proportion of self-employment is largely attributable to their massive presence in two regions in particular: South Asia (SA) and the Middle East and North Africa (MENA). Figure 2 suggests that nearly 9 out of every 10 employed persons in South Asia and 3 out of every 4 in MENA are self-employed. These indicate a staggering domination of self-employment in these regions. But even in other developing regions, self-employment is a very significant proportion of total employment, with the lowest presence in East Asia and the Pacific still accounting for nearly a quarter. Obviously, social protection through employment contracts would barely touch the surface of ensuring protection in such a context.

Figure 2

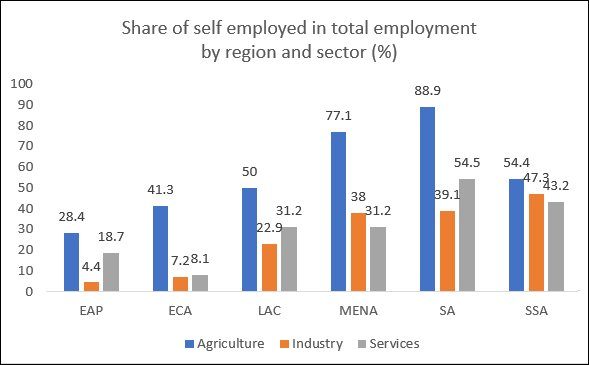

Figure 3

It is often believed that most self-employed persons tend to work in agriculture or in petty services, whereas industry (including manufacturing, construction and utilities) is more likely to have other forms of employment. But Figure 3 belies such simplistic conclusions. It is certainly the case that agriculture shows the highest proportion of self-employment among the three sectors, across all developing regions. In South Asia and Sub-Saharan Africa, the self-employed account for more than half or nearly half of services employment. But industry also shows significant shares of self-employment: in Sub Saharan Africa nearly 48 per cent, in South Asia and the MENA region nearly 40 per cent. Even in Latin America and the Caribbean self-employed workers are 23 per cent, or nearly a quarter, of total industrial employment.

How can such workers be provided with social protection based on their employment status? To begin with there is the issue of classification: the fact that many self-employed workers who are actually dependent on a particular company or enterprise are treated for legal purposes as independent. Classic recent examples of this are Uber drivers or Amazon delivery persons, whom these companies have tried to treat as “independent contractors” with whom they deal, in particular jurisdictions. But such examples have also proliferated in manufacturing, where large companies outsource particular parts of the production process to home-based workers or micro enterprises, in often very complex and global value chains. And the recent expansion of online-based platform work has created many more such disguised employment relationships. Dealing with these requires regulatory changes that recognise the impact of new technologies on the organisation of processes of production.

Self-employed workers bear all the risks of production, because of which their incomes also tend to be more casual, volatile and intermittent. Most often—and especially in the informal sector—their work is likely to be relatively low productivity and low remuneration. All this makes it even harder for them to contribute to social security schemes that implicitly rely on both employer and worker contributions that are rigid in terms of amounts and schedules. This in turn means that there is a case for dedicated social security schemes for self-employed workers, which would provide greater flexibility in contributions.

However, all this still leaves out the hundreds of millions of unpaid workers (dominantly but not only women) who also deserve social protection. This makes the case for a universal social protection floor even more compelling. As has been repeatedly emphasised, this can contain many elements, but there are some basic features that they must contain in all societies. These include access to essential health care, including maternity care; ensuring basic needs of children, providing access to nutrition, education, care and any other necessary goods and services; basic income security for persons in active age who are unable to earn sufficient income, in particular in cases of sickness, unemployment, maternity and disability; and basic income security for older persons (pensions).

This seems obvious, but few governments treat this with the importance and urgency that it deserves. Only wider public pressure would force a change.

(This article was originally published in the Business Line on January 9, 2023.)