NATO geopolitical strategy has now joined the ‘coalition’ of Western geoeconomic forces accelerating planetary heating,…

Misreading FDI Numbers C. P. Chandrasekhar and Jayati Ghosh

Exuding optimism at a time when most indicators point to economic stress across the world, India’s Ministry of Commerce and Industry put out a press release on 20 May celebrating what it describes as the “highest annual FDI (foreign direct investment) inflow of USD 83.57 billion in FY 21-22”. However, the details in the text of the release soon make clear that this is not much cause to celebrate, since the figure cited for 2021-22 ($83.57 billion) is only $1.6 billion or 2 per cent higher than the FDI inflow of $81.97 billion recorded in 2020-21. In an effort to downplay the implications of this marginal increase, the press release declares that annual FDI inflows have risen 20-fold in the last 20 years, from just $4.3 billion in 2003-04 and by 23 per cent between March 2020 and March 2022, which were Covid-afflicted years.

Implicit in this rhetoric, which exaggerates the significance of selectively chosen numbers, without placing them in context, is a belief that propaganda can trump a reality that is easily obscured. But that reality is stark, and is worth exploring, to assess the actual implications of the ‘record’ $83.57 billion FDI inflow figure for 2021-22. It needs noting that what is being cited here is the figure of “gross” FDI inflows, or inflow figures from which any outflows on account of repatriation or disinvestment of past inflows by foreign investors or investment abroad by resident entities (FDI outflows) have not been netted out.

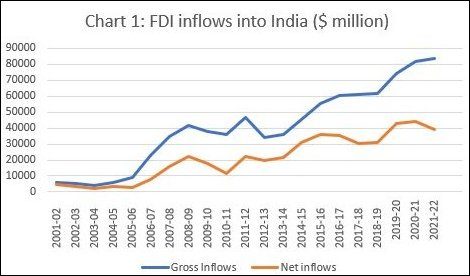

Staying with these gross inflow figures, though the gross inflow figure for 2021-22 is not remarkable by any means when placed in historical context, it does reflect a longer-term buoyancy that has two components to it (Chart 1). The first is a noticeable buoyancy in gross FDI inflows into India in the years after 2003-04, with some evidence of stagnation but no decline even in the years following the 2008-09 global financial crisis. The second is a sharp and consistent increase in gross FDI flows in the years after 2012-13.

India did considerably relax rules governing foreign investment in the years since the early 2000s, further reducing FDI caps in individual industries and providing more space for foreign investors. Capital gains tax rates were also slashed for investors in Indian equity. But that alone cannot account for the inflows into India. What was equally or even more important is the release of large volumes of cheap liquidity by the central banks of the advanced economies, especially the US Federal Reserve. This easy money policy was initially adopted in the run up to the 2008-09 crisis, then in the aftermath of that crisis as a stimulus response that continued for much of the following decade, and more recently in response to the economic stress resulting from the COVID-19 pandemic and associate lockdowns. The resulting overhang of cheap liquidity triggered a supply-side push of capital to developing countries—the so-called ‘emerging’ and ‘frontier’ markets. India was “successful” inasmuch as it was among those countries chosen as favoured destinations by the asset managers who directed these funds to new investment locations.

What needs to be noted is that much of this ‘direct’ investment was, like ‘portfolio’ investment flows, speculative in nature. Investors were looking not for long term returns from productive engagement earned as dividends but for capital gains and incomes earned from the difference between the low cost of capital in the source countries awash with cheap liquidity and the much higher returns in developing country markets. The scope for such investment identified as FDI is all the greater as the sums international investors are willing to allocate to any single investment has increased significantly, allowing them to acquire larger chunks of equity in a single enterprise. This matters because India’s official definition of foreign direct investment is investment through capital instruments by a person resident outside India (a) in an unlisted Indian company; or (b) in 10 percent or more of the post issue paid-up equity capital on a fully diluted basis of a listed Indian company. The latter, in particular, is presumed to reflect a lasting interest of the investor in the company. In the new environment a 10 per cent holding need not reflect any such interest and can be followed by an early exit of the investor.

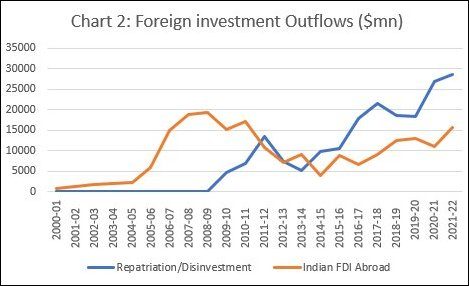

Seen in that light, a comparison of the relative movements of gross and net FDI inflows into India is revealing. As noted, net inflows are computed after deducting from gross inflows any repatriation or disinvestment of assets by existing foreign investors and any investments made by resident Indian entities abroad. As Chart 1 shows, during the years when gross FDI inflows have been rising (since 2003-04), while net FDI flows have also increased, there has been a growing shortfall of net relative to gross inflows, with the gap between the two widening over time. In the years between 2003-04 and 2008-09 (before the global financial crisis), this shortfall was explained by significant increases in investments abroad by resident entities, while repatriation or disinvestment of pre-existing foreign investment was minimal (Chart 2). The shortfall was because Indian firms were acquiring foreign firms and/or making new greenfield investments abroad as part of their global strategies. However, after 2008-09 there has been a shift, with a significant increase in the volume of repatriated or disinvested foreign capital, pointing to a tendency for so-called foreign direct investors with a “lasting interest” to opt out of their investments and exit. This explained much of the shortfall in net FDI inflows relative to gross inflows.

One implication of this is that gross inflow figures do not reflect in full the relative importance of FDI inflows in individual years. Thus, though between 2019-20 and 2021-22 gross FDI inflows rose despite the effect of the pandemic, net inflows fell mainly because of repatriation or disinvestment by existing direct investors. In troubled times direct investors have been behaving more like whimsical portfolio investors. This has meant that in 2021-22, as compared with an increase in gross inflows to $83.57 billion from $82 billion in the previous year, net inflows fell from $44 billion to $39.3 billion.

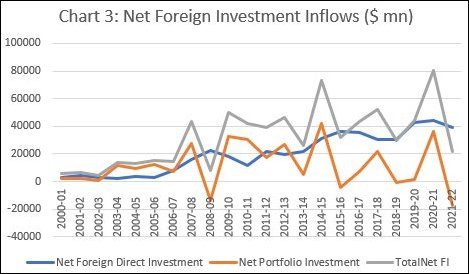

Meanwhile, portfolio flows have been volatile, fluctuating wildly because of increased uncertainty, with net portfolio investment inflows of $36.1 billion in 2020-21 and net outflows of $17.3 billion in 2021-22 (Chart 3). Combined with the decline in net FDI inflows, this has meant that aggregate net foreign investment flows stood at just $22 billion in 2021-22, as compared with $80.1 billion in 2021-22. That is no cause for celebration and reveals the government’s hype for being what it is.

(This article was originally published in the Business Line on May 30, 2022)