Donald Trump’s top economic advisor claims the President has weaponised tariffs to ‘persuade’ other nations…

Unwarranted Confidence C. P. Chandrasekhar and Jayati Ghosh

Global inflation, the launch of a monetary tightening cycle in the US with increased interest rates, depreciating exchange rates and the fall out of the war in Ukraine, are forcing many countries to borrow their way out of balance of payments difficulties. This, however, is not the best time for that manoeuvre, given the uncertainty that overwhelms the global financial system. Yet, one country that seems less affected by these circumstances is India. Despite outflows of foreign capital from India’s financial markets in the first quarter of 2022, the stock market has not fared too badly. And the official assessment of the country’s external debt situation is that “external debt continues to be sustainable and prudently managed”. [India’s Quarterly External Debt Report For Quarter Ending December 2021, Ministry of Finance March 2022].

There are grounds for that confidence. India’s external debt to GDP ratio stood at 20 per cent at the end of 2021. That is comfortable and much below the ratios characterising most oil importing developing countries. And foreign exchange reserves, at $632 billion, seem ample to handle any contingency. So, while the times are tough, India seems to have prepared itself to face any external shock.

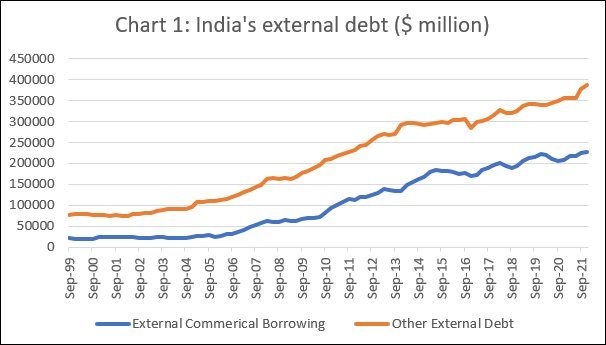

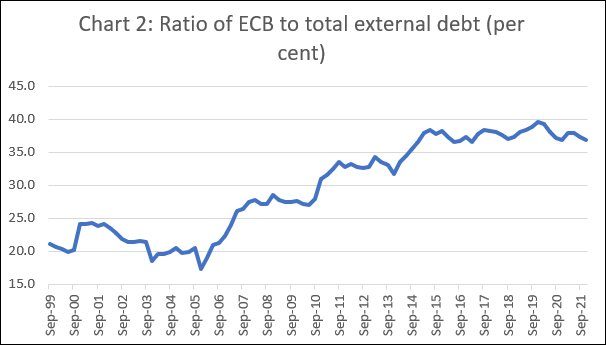

However, there is no room for complacency. This is because during the years since the global financial crisis, when easy money policies in the developed countries resulted in an explosion of global liquidity and drove interest rates down, India relaxed its stance with regard to external commercial borrowing by the private sector. Given the differentials in interest rates between global and domestic markets, Indian financial and non-financial firms borrowed money abroad to finance their expansion at home as well as to substitute high-cost domestic debt with cheaper foreign debt. Between end-December 2008 and end-December 2021, the dollar value of India’s outstanding debt rose from $230 billion to $615 billion. Much of that increase was on account of commercial borrowing, which rose from $65 billion to $226 billion between those two dates (Chart 1). That took the share of external commercial borrowing in total outstanding external debt from 28.5 per cent at the end of December 2008 to a peak of 39.6 per cent at the end of December 2019, after which it declined to 36.8 per cent at the end of December 2021 (Chart 2).

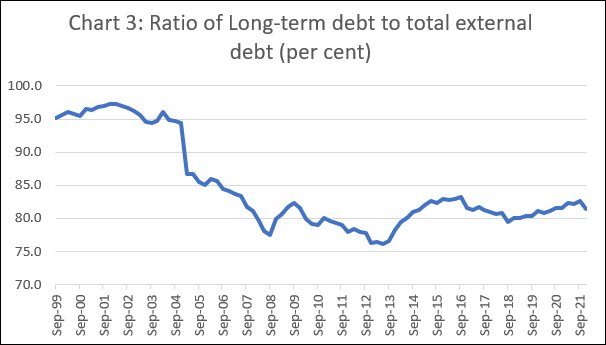

Before this spike in commercial borrowing there was another noteworthy trend in the country’s external debt position. This was a decline in the share of long-term debt in the total from 95 per cent at the end of September 1999 to 80 per cent at the end of December 2020, after which it fluctuated around that level and stood at 82 per cent at the end of December 2021 (Chart 3). If there is any shock that discourages older short-term creditors from rolling over their loans and new lenders from providing additional credit, there would be a net outflow of capital from the country.

Moreover, the aggregate level of exposure to debt is not the best indicator of the level of vulnerability. A feature of India’s boom years since the early 2000s was the accumulation of large volumes of debt in the hands of a few large corporates and corporate groups. A cursory examination of the list of borrowers resorting to external commercial borrowing reveals the same tendency. This is understandable, since it is unlikely that smaller firms would be able to access commercial borrowing markets abroad at attractive interest rates. Much of this debt has been incurred to invest in activities that are not export oriented and are unlikely to yield revenues denominated in dollars. Thus, a concentration of such private external debt in the hands of a few large corporates is inevitable. But this also raises the level of vulnerability, especially as the rupee depreciates vis-à-vis the dollar, which is the preferred currency for denomination of international cross-border debt. To the extent that dollar liabilities associated with external debt exposure are not adequately hedged—which according to reports they are not a decline in the relative value of the domestic currency increases the domestic currency volumes required to service that debt. This can, in troubled times when margins are squeezed, erode repayment capacity and even lead to default.

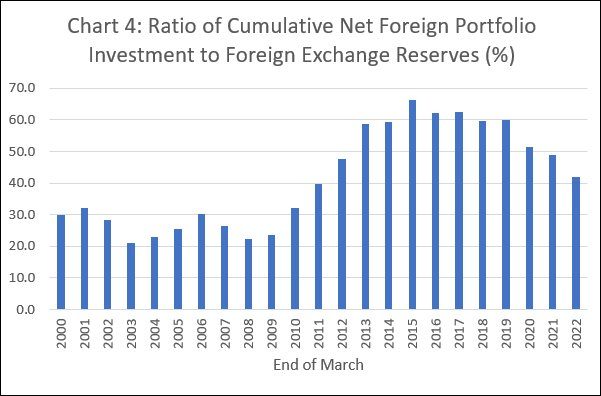

But increased commercial borrowing, higher dependence on short term debt and concentrated exposure are not the only factors that need to be flagged when discussing external vulnerability. It is also worth noting that India has over the liberalisation years become host to large volumes of footloose capital. For example, the cumulative net legacy investments by foreign portfolio investors in debt and equity markets has risen from $69 billion at the end of March 2008 to $265 billion at the end of March 2022. (This includes some of the external commercial borrowing referred to earlier.) This is not a small proportion of the aggregate foreign reserves of the country. Foreign reserves fluctuate for multiple reasons, including sales or purchases of dollars by the central bank to shore up or depreciate the rupee vis-à-vis the dollar. But it is suggestive that the ratio of cumulative net foreign portfolio investments in the country to its foreign exchange reserves rose from 29.9 per cent at the end of March 2000 to 66 per cent in end-March 2015, and then declined to 62.5 per cent end-March 2017, 60 per cent at the end of March 2019 and 42 per cent at the end of March 2022. The decline over the last three years was the result of a spike in reserves from $413 billion at the end of March 2020 to $632 billion at the end of March 2022. But this not necessarily because of adjustments that reduced vulnerability. Rather two special factors influencing the level of reserves also seemed to have played a role: reserve accumulation because of dollar purchases by the RBI to stall excess depreciation of the rupee, and the transfer to India of its share of SDR 12.57 billion out of the special 456 billion SDR allocation made by the IMF in August 2021, which raised India’s reserves by the equivalent of $1.55 billion. Portfolio investors still account for a large share of India’s “borrowed” reserves, eroding their value as insurance against capital exit. These are investors who are prone to exit rather rapidly in herd-like fashion when conditions turn for the worse in their perspective either in the host country or at home. Not surprisingly, over the first three months of 2022, when uncertainty over conditions in global markets and regarding monetary policy adjustments that would be made by the world’s leading central banks increased, around $15.5 billion was pulled out of the country by foreign portfolio investors.

If that exit continues and accelerates not only would the balance of payments be destabilised, but the currency can depreciate rather quickly, making India’s debt and foreign investment exposure less comfortable than it seems.

(This article was originally published in the Business Line on April 4, 2022)