The first edition of the IDEAs African Network (IDAN) conference will be held from 26…

So what’s the Actual Rate of Inflation? C. P. Chandrasekhar and Jayati Ghosh

Inflation has become a problem in India once again, well before it emerged globally and in the advanced countries as a major concern. In India, inflation rates of 6 per cent and above were evident even during the pandemic collapse, when much of the rest of the world suffered deflation. This was largely due to cost-push pressures resulting from the central government’s continuous increases in fuel taxes, which effectively increased the costs of producing and transporting goods and services.

Since then, and especially since the Ukraine war, global prices of fuel and other commodities (including food crops like wheat) have shown significant increases, and other supply chain issues are driving inflation up in most parts of the world. India is no exception to this, with the past few months showing dramatic rises in the Wholesale Price Index (WPI) which has been showing double-digit inflation for several months now.

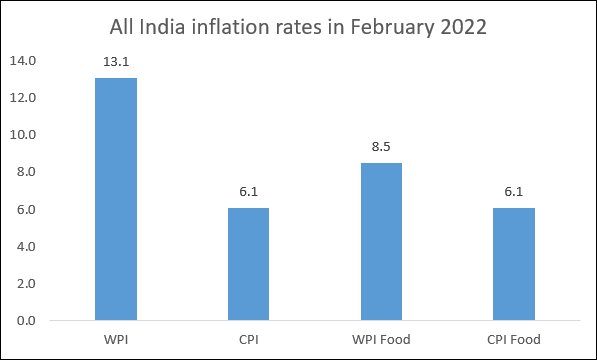

However, one striking feature of the Indian scenario is the difference between inflation as measured by the WPI and that evident in the Consumer Price Index (CPI). Figure 1 indicates the difference just for the most recent month for which data are available, February 2022. The annual increase in the WPI was more than 13 per cent; the CPI increased at less than half that rate.

Figure 1

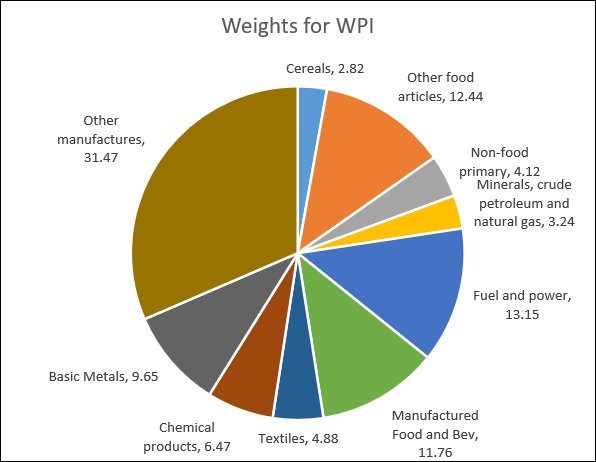

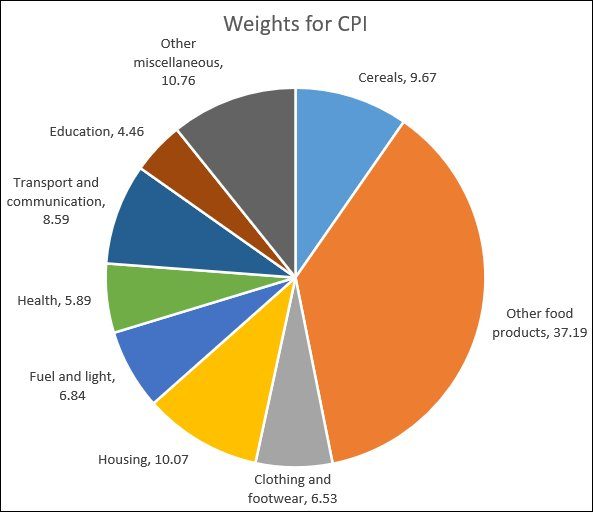

Differences between WPI and CPI rates of inflation have occurred before, and have typically been ascribed to the different weights in the two indices. These weights are indeed very different. To begin with, the WPI excludes services altogether, covering only produced goods. Within goods, the CPI gives a much higher weight to food articles, which account for nearly 46 per cent of the basket, compared to only 15 per cent in the WPI. (In fact, the CPI for rural areas gives as much as 54 per cent weightage to food and beverages, while in urban areas it is 36 per cent.)

Figure 2a

Figure 2b

Figures 2a and 2b provide some indication of how much the two baskets vary. The differences extend well beyond the significance of food items. Services of various kinds account for more than 27 per cent of the CPI, and are not in the WPI at all. Fuel and power (a major driver of WPI inflation) has a much lower weight of less than 7 per cent in the CPI, compared to nearly double that in the WPI.

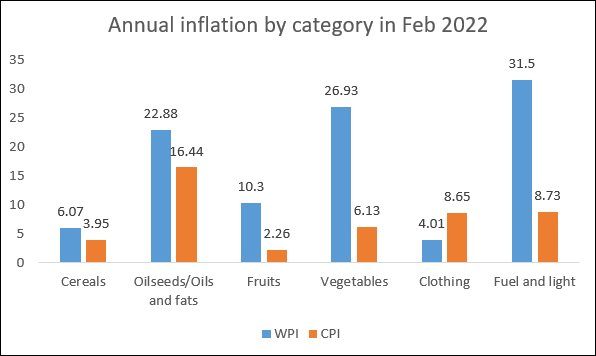

However, the reasons for the variation in the two prices indices may be more complex. As was evident from Figure 1, even with respect to food items, the WPI has been increasing much faster than the CPI in the recent past. Figure 3 provides a more granular look at specific items, and shows the substantial variation across WPI and CPI even within fairly specific categories. Interestingly, other than for clothing (for which the CPI inflation has been higher) the WPI index suggests significantly faster price increases across a wide range of goods.

Figure 3

Some of these differences are relatively easy to explain. The retail price of food (and especially cereals) has been held down because of the role of the Public Distribution System, which provides food grain at subsidised prices, and in which the pandemic period provision of some free food grain has also played a role. The retail prices of fuel were controlled for what appear to be obvious political reasons: oil and gas prices (which are effectively administered prices because of the big share of taxes) were not increased despite global price hikes, until the recently concluded Assembly elections in several important states. It is likely that they will be increased once again now.

Even so, the faster increase in WPI relative to CPI deserves some scrutiny. The reference inflation rate used by the Reserve Bank of India is the CPI; it is also the inflation rate that most closely tracks how people in general experience price rises. The CPI is based on a survey of different retail markets. The WPI, by contrast, is derived from data on bulk sale of commodities at the first point of transaction: ex-factory level for manufactured products, ex-mine level for mineral products and mandi level for agricultural products.

It is therefore reasonable to assume that WPI inflation will eventually be reflected in higher CPI inflation, and that both people and policy makers should brace themselves for higher retail prices in the near future.

But WPI inflation has been higher than CPI inflation for a while now, so it could be asked why past WPI increases have not already been reflected in the CPI. Aside from the specific commodities (food grain and fuel) for which government policy clearly has a proactive role, what could explain this discrepancy? Clearly this needs much more investigation, but it is possible that retail prices have not risen so much because mass consumption demand still remains hugely suppressed. Consumption was down even before the pandemic; since then, the collapse in livelihoods, the uneven and unequal recovery and the continuing lack of employment opportunities have further reduced the ability of the bulk of households to increase spending.

In such a market, retail sellers cannot afford to increase prices too much because they will not find buyers. So this could have involved a squeeze of distributive margins, especially for small retailers. If so, this would correspond to the squeeze on micro, small and medium enterprises that have lost out to the larger companies that they supply to. It could also reflect a squeeze on the margins taken by small retailers, who are among the largest group of self-employed workers not involved in agriculture.

The difference between WPI and CPI inflation is therefore something that deserves to be taken more seriously. More than just a statistical anomaly, it could be pointing to wider systemic changes in the Indian economy.

(This article was originally published in the Business Line on March 21, 2022)