Click here for the Concept Note Applications to be accepted until May 10, 2025, 23:59…

Collateral Damage: Ukraine invasion and energy markets C. P. Chandrasekhar and Jayati Ghosh

Following Russia’s irrational and devastating invasion of Ukraine, global energy markets have been in turmoil. Russia is the third largest producer of oil in the world and, more importantly, the world’s largest exporter of oil and gas and the second largest exporter of crude oil after Saudi Arabia. In December 2021, it exported 7.8 million barrels per day (mb/d), of which crude and condensate accounted for 5 mb/d, or 64 per cent. So, disruption of supplies from that country are bound to roil energy markets.

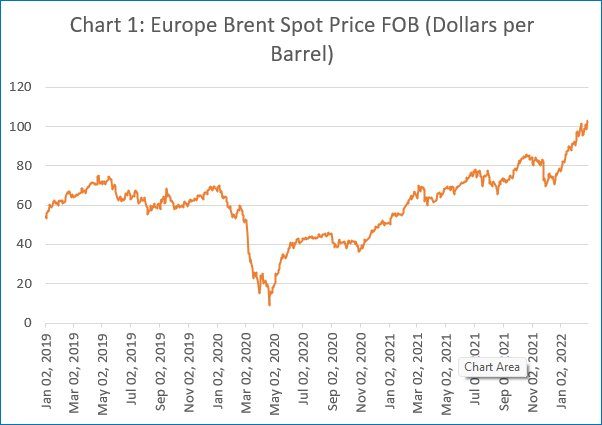

The evidence is as expected. Prices of oil and natural gas that were recovering from the lows they touched during the pandemic have risen sharply, hitting energy importing countries adversely. The price of Brent crude that had fallen to a low of $9.1 a barrel at the height of the pandemic in April 2020 when the trade was shut down, had risen to more than $80 a barrel by November 2021 (Chart 1). And then, after a short downturn, the price of Brent rose to $110 a barrel on February 28 and $118 a barrel on March 5, driven by the uncertainty following the invasion of Ukraine on February 24.

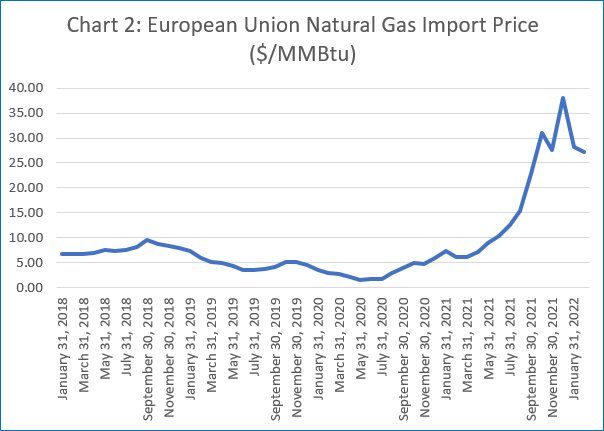

Russia is an important exporter of natural gas too, especially to Europe. The price of natural gas had risen from around $2 per MMBtu at the end of July 2021 to touch $38 per MMBtu at the end of December, with the economic recovery and enhanced winter demand (Chart 2). It then declined, touching $27.23 per MMBtu at the end of February. The fear is that prices would rise again as finding alternative sources of natural gas and LNG to replenish inventories could prove difficult.

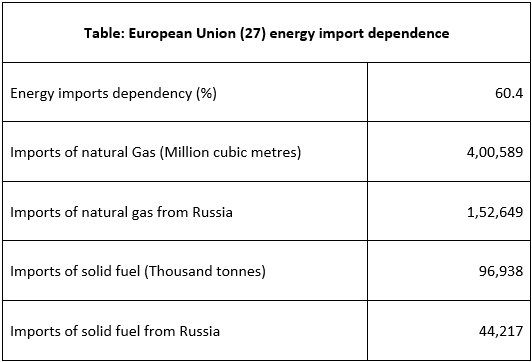

Europe is the region that is bound to be most affected. In 2020, the energy import dependence of 27 European economies was almost two thirds of domestic consumption. Russia accounts for 38 per cent of the imports of natural gas and 48 per cent of the imports of solid fuel into the union (Table). This is bound to trigger energy shortages and energy price inflation, as experience shows. For example, the pre-December spike in gas prices was also attributed to Russia holding back supplies of gas to Europe through pipelines traversing Ukraine and Poland, in order to get the German government to accept gas supplied through the Nord Stream 2 pipeline that directly connects to Germany across the Baltic Sea. Russia had denied that allegation, but the perception underlined how crucial Russian supplies were for Europe.

Reduced Russian exports would also destabilise global markets, especially as the OPEC countries have expressed unwillingness to step up production and exports to make up for the shortfall in supply from Russia. Unregulated private players and speculative investors are likely to exploit the opportunity. As a result, even the US, which draws just 7 per cent of its imports from Russia, and would be able to manage for a time with imports from other sources and by running down its strategic reserves, is experiencing a spike in oil and gas prices.

The point to note is that these developments occurred even though oil and gas were expressly left out of sanctions, in what was a clearly contradictory US policy of imposing sanctions on Russia. Financial institutions that can route payments for Russian oil were also excluded. Despite this, imports from Russia have fallen for a number of reasons. First the disruption caused by the war. Second, the fear among dealers that they may be indirectly flouting the sanctions by engaging with firms linked to oligarchs who are being sanctioned. Third, voluntary cuts in imports from Russia by some European countries in solidarity with Ukraine. But the fact remains that despite Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky’s repeated urgings for stronger sanctions and inclusion of oil and gas, the Biden administration is still mulling over the implications and playing safe by postponing a decision. Meanwhile, it is attempting to persuade its European allies, especially Germany which receives 30 per cent of its oil imports from Russia, to rely on more expensive imports of liquified natural gas from the US to meet its needs.

The implications for the US and the European nations go beyond the specific issue of higher oil and gas prices and possible shortages. Oil as a universal intermediate enters in multiple ways into the costs of commodities, making oil price increases a driver of inflation even in the best of times. But these times are not the best, as the advanced nations are just beginning to battle with high inflation that has returned after decades to haunt them. Pressure has been building on advanced-country central banks to pull back on the low interest rates and quantitative easing policies they have pursued for close to two decades, in the belief that inflation is no longer a problem in capitalist economies.

Besides the fact that a sharp retraction of the easy money regime can subvert the slow recovery from the Covid-induced crisis, there is a real danger that financial markets that had been riding to speculative highs fed with this cheap money could unwind very quickly or even collapse. So the challenge is to address inflation without driving the economy into experiencing a hard landing. With oil prices becoming one more factor contributing to inflation, that task is looking to be impossible.

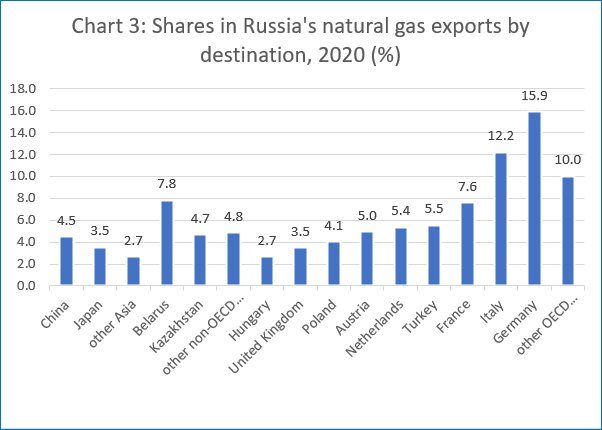

The US and Europe are hoping that a fall in its oil exports would hurt Russia so much that it would keep supplies flowing, even while desperate attempts to end the war are on. Oil and gas contribute close to one-fifth of Russia’s GDP, provide two-fifths of budgetary resources and 60 per cent of export revenues. European OECD countries (including the United Kingdom) account for 70 per cent of Russian exports (Chart 3). So, the two need each other, but as of now it is unclear whether that would ease the looming energy crisis in the region.

There is no clarity on how long the Ukrainian invasion will last and what its political and strategic consequences would be. But the energy crisis it has triggered in a world wounded severely by the 2008 global financial collapse and the COVID-19 pandemic would only heap even greater burdens on the world’s vulnerable populations.

(This article was originally published in the Business Line on March 7, 2022)