Sri Lanka has witnessed a major political shift in recent months. Anura Kumara Dissanayake of…

The Global Divergence gets Bigger C. P. Chandrasekhar and Jayati Ghosh

The Covid-19 pandemic operated to expose various global inequalities in their stark form, but it has also further accentuated them at unprecedented scale and speed. The latest World Economic Outlook from the IMF, released in late October 2021, provides further evidence of how the global divide has increased through the course of the pandemic, most of all the gap between advanced economies and the rest of the world.

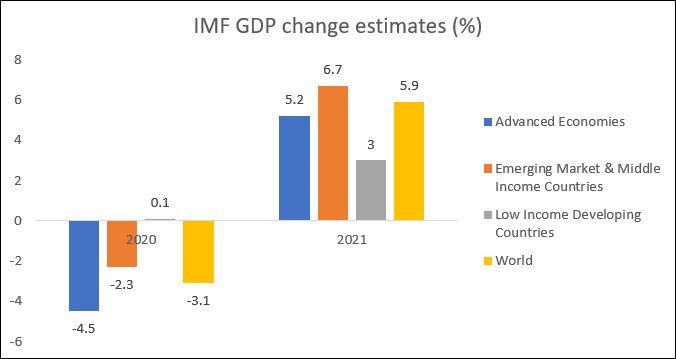

On the face of it, in terms of GDP changes alone, the divide does not appear to be so stark. Figure 1, which provides IMF estimates of GDP change in the current and past year, suggests that the advanced economies experienced larger declines and are recovering more slowly than emerging market and middle income countries.

Figure 1

Source: Data from IMF World Economic Outlook October 2021

Yet there are good reasons to be careful about such a quick conclusion. The numbers for the emerging markets are massively affected by China, which accounts for an increasing proportion of the aggregate GDP of this set of countries, and which managed to control the spread of the novel coronavirus and to revive its economy quite quickly from early 2020. Unlike most economies in the world, the Chinese economy did not decline in 2020 but grew by 2.3 per cent; and it is projected to increase in size by 8 per cent in 2021. Most other developing countries, by contrast, experienced quite significant GDP declines in 2020 and even by the end of 2021 they would not have recovered to pre-pandemic levels of output.

This is true even within Asia, where other emerging market economies showed large declines in 2020 (like India with a GDP fall of 7.3 per cent) and/or much slower recovery in 2021 (ASEAN-5 with 2.9 per cent and other developing Asian countries with 1.7 per cent). Latin America and the Caribbean countries together declined by 7 per cent in 2020 and are projected to increase by only 6.3 per cent in 2021, staying well below pre-pandemic levels. Similar trends are evident for the MENA region and in Sub-Saharan Africa.

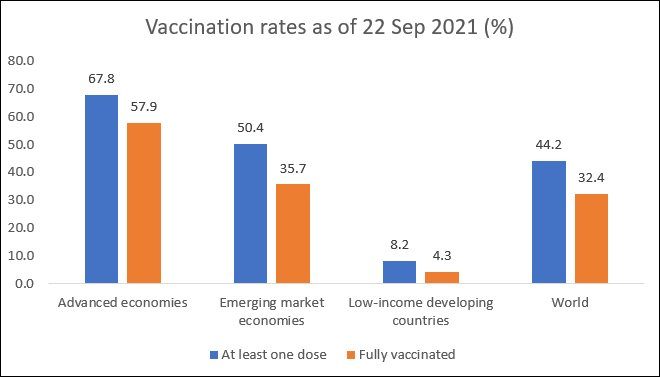

Figure 2

Source: Data from IMF World Economic Outlook October 2021

One important reason for this relative lack of recovery in the developing world (other than China) is the persistence of the pandemic. This in turn can be linked to the uneven and unbalance spread of vaccination across the world, also noted by the IMF and described in Figure 2. Vaccine grabbing and then hoarding by the rich countries, as well as their continued insistence on maintaining intellectual property rights that give monopoly power to large pharma companies, have limited global supplies and skewed the distribution of whatever doses are available. Condemnation of such practices by the World Health Organisation and other international bodies, as well a developing country governments and people across the world, appears to have done relatively little to shake such unjust policy stances in the handful of rich countries that are doing this. This is globally counterproductive, but it also bodes ill for international cooperation to deal with other ongoing challenges facing humanity, including climate change.

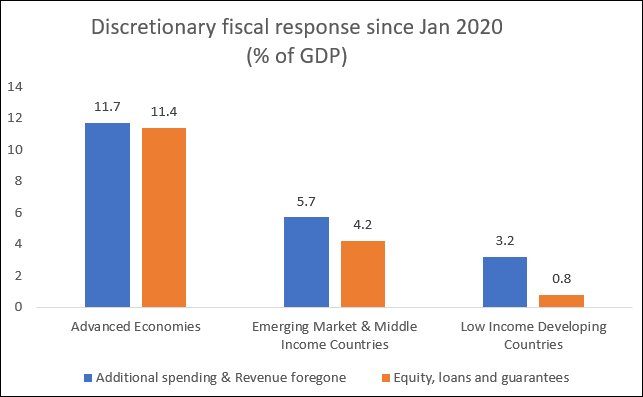

But another, and possibly more important, reason for the great economic divergence is the massive difference in fiscal responses evident throughout this pandemic, between rich advanced economies and all other parts of the world. Figure 3 provides some summary data on this, covering the period from January 2020 to late September 2021. Advanced economies as a group have provided significant additional funds during this period, both in terms of increased public spending and revenues foregone through tax concessions. They have also provided significant amounts through equity, loans and guarantees of various kinds. Together these amounted to 23.1 per cent of 2020 GDP – in other words, nearly a quarter of the first pandemic year’s GDP! This level of fiscal increase has not been seen in capitalist economies outside war time, not even during the storied New Deal of Roosevelt in the USA to combat the Great Depression. Of the total global additional fiscal measures amounting to about $10.8 trillion, the ten advanced countries in G20 accounted for nearly 80 per cent, and the US alone accounted for almost half.

Figure 3

Source: Data from IMF Fiscal Monitor October 2021

By contrast, emerging market and middle income countries spent much less – less than half that amount relative to GDP, and also less than they had spent after the Global Financial Crisis of 2008-09. Low-income countries spent an even smaller fraction relative to GDP, and certainly far below what was required to reverse the economic decline. It is therefore not surprising that their recovery has been slower and—in some cases—unlikely to bring their economies back even to pre-pandemic levels even in the next two years.

But meanwhile, because the rich countries and China have been spending so freely and enabling faster recovery, this is already having an impact on some crucial global prices, such as those of fuel and food that have massive effects on import-dependent developing countries. Global oil prices were at their lowest recent level in April 2020 when the pandemic disrupted trade and economic activity everywhere; but since then, they have gone up by three times. Food prices have increased by 30 per cent. These price changes effectively add to the adverse economic shocks being experienced by developing countries. Emerging and developing countries as a group have experienced faster increases in consumer prices as a consequence.

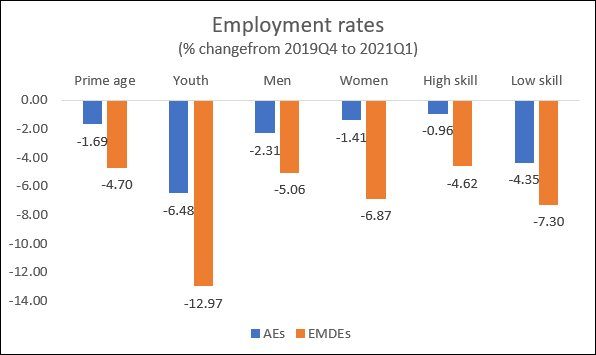

The implications of the slow recovery and the inadequate fiscal response in the developing world have also made themselves felt in the labour market. Figure 4 compares changing employment rates (active workers to population of working age) across advanced economies and emerging market and development economies. The declines in employment have been greater in the developing world across every category of worker, whether considered by age, gender or degree of education. The drop in youth employment is of special significance given the different demography of most developing countries that are still experiencing a youth bulge.

Figure 4

Source: Data from IMF World Economic Outlook October 2021, based on ILO

Bear in mind that in the developing world, 70 per cent of workers are informal, with little or no social or legal protection (compared to only about a quarter in the advanced economies). This means that many of those who are still employed in emerging and developing countries are likely to be experiencing falling real wages, and often even declining money wages. So the divergence in living and working conditions across these two tracks is likely to be even greater.

All this does not even consider the internal economic inequalities that have festered and grown during the pandemic. But surely, this level of inter-country inequality is also unsustainable, and likely to lead to different forms of unpleasant responses. It will also, inevitably, affect the economic prospects of the rich countries as well. It is truly astonishing that this obvious realities still seem to be ignored by the policy makers of the North.

(This article was originally published in the Business Line on November 1, 2021)