The weaponization of tariffs by US President Donald Trump has clearly generated fear and loathing…

Mixed Signals on the Inflation Front C. P. Chandrasekhar and Jayati Ghosh

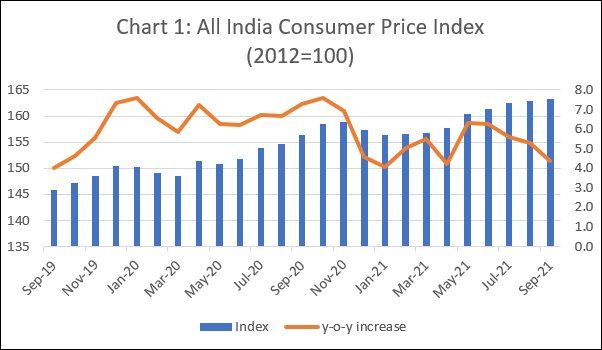

As COVID-19 infection rates fall and demand revives the world over, the new global fear is that persisting supply chain disruptions could trigger inflationary trends that would be more than transitory. In India, however, the consumer price index that was on the rise between January and July 2021 has since been in decline (Chart 1) with the inflation rate relative to the corresponding month of the previous year falling from 6.3 per cent in June 2021 to 4.3 per cent in September of that year.

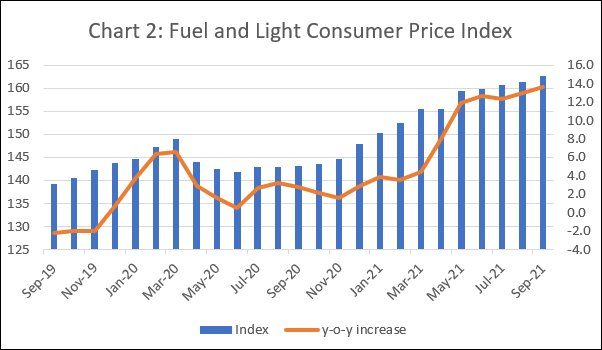

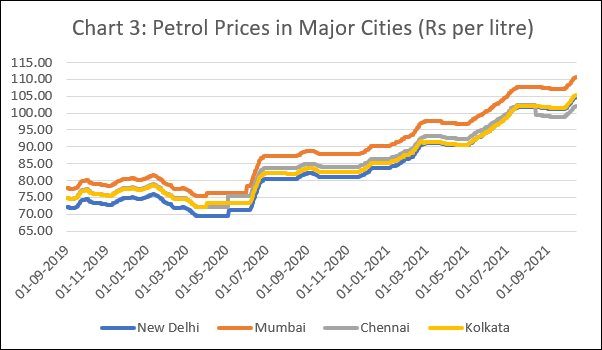

This is indeed surprising for two reasons. First, a relentless spike in the prices of petroleum products has led to a persistent rise in the Fuel and Light component (Chart 2) of the consumer price index (CPI), which has a weight of 6.8 (of 100) in the all-India CPI with 2012 base. A combination of rising global prices and hikes in government taxes, which were raised when prices were low and not lowered when prices rose, have made fuel the talking point and a leading driver of inflation expectations. The price of petrol in Delhi, for example, has risen by more than 50 per cent between the early days of the pandemic in May 2020 and the present (Chart 3). A significant part of the rise in petrol prices over the last two years was due to increasing central excise duties, which were raised several times over this period. Between 1 November 2019 and 16 October 2021, excise duty on petrol in Delhi increased from Rs. 19.98 per litre to Rs. 32.90 per litre or by 65 per cent. By October 2021, taxes (excise and VAT) accounted for 54 per cent of the price for petrol in Delhi.

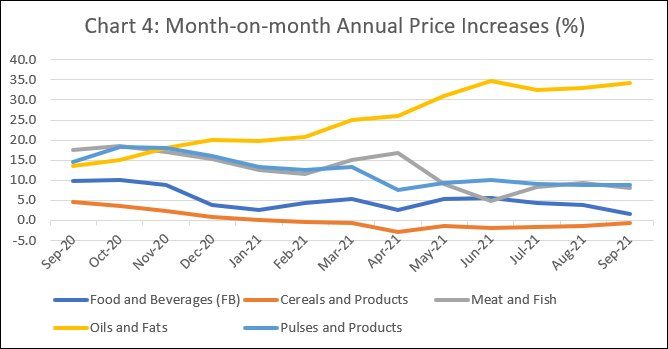

Second, with India still dependent on imports to meet anywhere up to two thirds of its edible oil consumption, rising global prices, especially of palm oil, are contributing to a domestic price spike as well. The consumer price index for oil and fats recorded an average year-on-year increase of 33 per cent during the months of May to September 2021, as compared with 17 per cent during September 2020 to January 2021. It is true that the relatively low weight of 2.38 that this group has in the overall consumer price index tempers the effect of this rise on overall consumer price inflation. But the magnitude of the rise significantly neutralises the benefits of the small weight. With global prices of food products (including vegetable oils) expected to remain firm, this is a cause for concern.

Other products in the Food and Beverages group, while recording a fall in the rate of inflation are still characterised by absolute price increases that are substantial. Thus, the Pulses and Products component of the CPI (weight 2.4) recorded an average y-o-y inflation of around 9 per cent during May to September 2021, which though lower than the average of 16 per cent recorded during September 2020 to January 2021, was still close to double digit. Similarly, the corresponding figures for the Meat and Fish component of the CPI (weight 3.6) were 7.9 and 16.2.

If despite these trends in individual commodity groups the overall inflation in the prices of Food and Beverages (weight 45.9) was on average at a comfortable 4.1 per cent during May to September 2021, this was largely on account of Cereals and Products with a significant weight of 9.7 in the CPI. The price index of this component fell on average by 1.4 per cent over the May to September 2021 months, as compared with a rise of 2.4 per cent during September 2020 to January 2021 (Chart 4). A number of factors played a role here. Consecutive good monsoons had delivered consecutive record harvests. Procurement by the government, pressured in part by the farmers agitation and the need to make up for market disruptions during the pandemic, was also at extremely high levels. And increases in the minimum support price were moderate. The MSP for kharif paddy (Grade A) was raised by just 2.9 per cent and 3.8 per cent for the 2020-21 and 2021-22 crop years and that for rabi wheat by 2.6 and 2 per cent respectively. Given the rise in costs, especially of fuel and fertiliser, these increases seem modest. Import prices of fertiliser have risen sharply, and subsidy increases have only partially neutralised the increase. The import prices of Urea and Muriate of Potash have reportedly more than doubled and that of Di-ammonium phosphate has risen by more than 80 per cent when compared with levels a year ago. With fertiliser subsidy hikes not matching up and fuel prices climbing, cultivation costs are on the rise. Given such cost increases, it does seem that MSP increases are being moderated to exploit the benefit of abundant supply and keep cereal prices down, to neutralise price spikes elsewhere.

However, unless global price trends across a range of commodities are reversed, it is likely that the benefit of a cereal price buffer against inflation would prove difficult to sustain. Especially because of the government’s reluctance to “burden” the budget with larger fertiliser and food subsidies with the aim of dampening inflation. Government pronouncements of controversial plans to enhance output of palm oil to reduce import dependence have come a little too late to deal with this bout of price increase in vegetable oils. And given the fact that cost push is a crucial driver of current inflationary trends, there is no help to be derived from interest rate hikes, the efficacy of which in the event of even a demand led price spike is also suspect. For a citizenry still recovering from multiple blows to their standard of living, not least of which was the fallout of the pandemic and its handling, this threat of inflation is more than bad news.

(This article was originally published in the Business Line on October 18, 2021)