Donald Trump’s top economic advisor claims the President has weaponised tariffs to ‘persuade’ other nations…

How Important is MSP-based Procurement C. P. Chandrasekhar and Jayati Ghosh

Though not featuring in any of the three farm laws, the Minimum Support Price (MSP) at which the government promises to procure 25 different commodities through different agencies, is a central issue in the standoff between the government and protesting farmers. The latter fear that the implementation of the three laws will end the MSP regime, with the government withdrawing from procuring output at a remunerative cost-plus price. The response of the government and advocates of reform has been that sale at the MSP is resorted to or available only to a few farmers. That opportunity, it is argued, would continue to exist under the new regime, which would also offer alternative, lucrative marketing opportunities for farmers.

The notion that only a few farmers avail of the MSP when marketing their produce has been in circulation for some time, strengthened by the assertion of the Shanta Kumar Committee that only a “miniscule of agricultural households in the country” benefit from procurement. That conclusion was based on the evidence from the National Sample Survey’s Situation Assessment of Agricultural Households of 2013 that only 6 per cent of agricultural households recorded sales of paddy and wheat at the MSP. Besides the fact that there are many other crops that have seen increasing procurement by government agencies, this assertion was misleading because it referred to an average across the country, whereas the figure in states where procurement had been implemented well touched much higher levels.

The recently released Situation Assessment Survey for 2019, covering the July 2018-December 2018 and January 2019-June 2019 agricultural seasons, provides us a picture of the current relevance of the MSP. The survey estimates the number of rural agricultural households (HHs) at 93.1 million or 54 per cent of all rural households and land used solely for crop production (excluding mixed use holdings for cultivation and grazing, say) at 74 million hectares or 82 per cent of operated area.

Paddy and wheat (the principal staples) are by far the most popular crops for farmers, with 62.5 per cent of agricultural households reporting cultivation of paddy (in either season) and 41 per cent reporting cultivation of wheat. The only other crop with more than 10 per cent of agricultural HHs engaged in production is maize. Not surprisingly, rice and wheat account for 29.6 per cent and 18.7 per cent of the total value of the harvest of a set of selected MSP-receiving crops of Rs. 6.98 billion over agricultural year 2018-19. These crops matter greatly for the livelihood of the farming community.

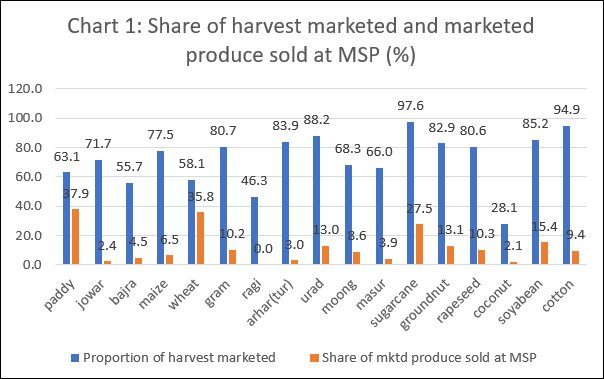

Needless to say, not all of the crop harvested is sold. Of the combined total of agricultural households reporting cultivation of paddy and wheat in each of the seasons, only 54 per cent reported sale of part of their crop. The proportion of the harvest sold in either season amounted to 63 per cent for paddy and 58 per cent in the case of wheat. Of the output sold, that which was sold under MSP amounted to 37.9 per cent in the case of paddy and 35.8 per cent in the case of wheat (Chart 1).

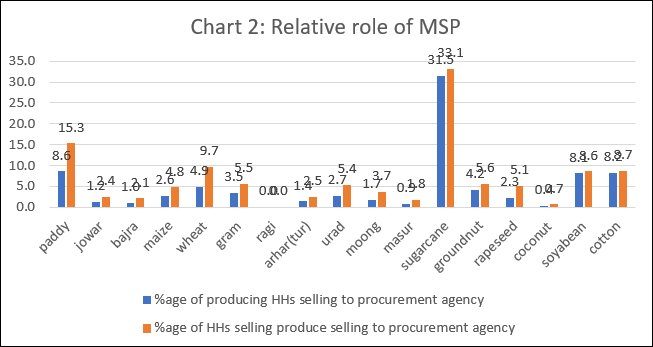

At the “aggregate average” level, household participation in the MSP regime does not seem to have changed much. Only 8.6 per cent of agricultural households cultivating paddy sold to a procurement agency, with the figure for wheat at a low 4.9 per cent. If we exclude households cultivating for self-consumption, however, the proportion of households selling to a procurement agency among those selling any part of their crop at all stood at 15.3 per cent in the case of paddy and 9.7 per cent in the case of wheat.

The main reason for more than sixty per cent of the marketed crop not being sold under the MSP appears to be a lack of awareness of the operation of the scheme. This could reflect the inadequate coverage of the public procurement system. Indeed, even among those aware, the absence of local access to the procurement system played a role, as did an inadequately remunerative level of the procurement price in the case of many crops. But even when procurement prices were unremunerative, the open market did not always provide a better alternative. The proportion of households selling a part of their crop and aware of the procurement system, which said they did not sell to a procurement agency because they could get a higher price than the MSP, was close to negligible. If farmers do have access to local procurement and are aware of the system, they do take advantage of MSP procurement facilities.

This is not true of just paddy and wheat. As Chart 2 shows, marketed surpluses are high in a number of the crops benefiting from a support price. The share of marketed surplus sold at the MSP was close to 30 per cent in the case of sugarcane and above 10 per cent in the case of gram, urad, groundnut, rapeseed/mustard and soyabean. In all probability, the reason there was not higher reliance on a procurement agency in most crops, was because of the absence of procurement facilities on the ground or because the support price was not attractive enough.

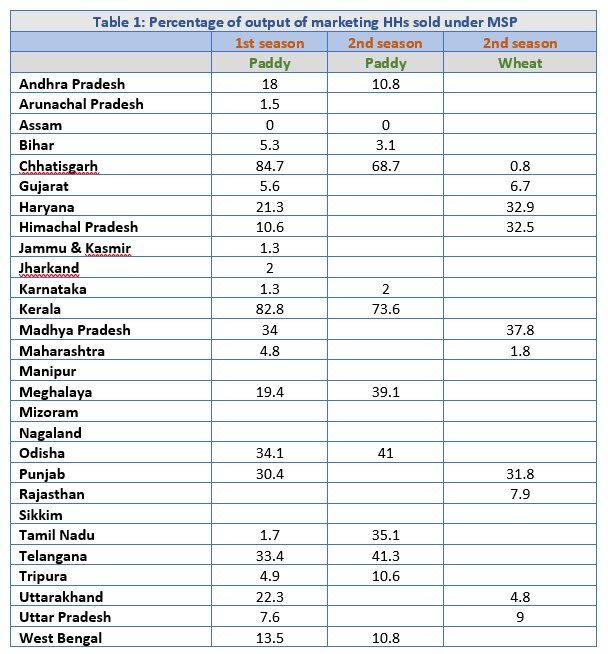

There is wide variation in the significance of procurement across states. In the case of paddy for example, the proportion of marketed output sold under the MSP scheme was 84.7 per cent and 68.7 per cent during the first and second seasons of 2018-19 in Chhatisgarh, 82.8 and 73.6 per cent in Kerala, and 33.4 per cent and 41.3 per cent, as compared with the national average of 23.7 and 24.7 per cent. In the case of wheat, the figure for Madhya Pradesh was 37.8 per cent, that for Haryana 32.9 per cent, for Himachal Pradesh 32.5 per cent, and Punjab 31.8 per cent, whereas the national average stood at 20.8 per cent (Table 1). So there is widespread and active procurement in some parts of the country. Studies indicate that a push from the state government and state level agencies accounts for this difference.

In sum, the problem with the MSP is definitely not that it is of marginal or no benefit to farmers, except in a couple of crops and in a couple of states. The problem lies in the inadequate spread of the procurement apparatus to cover more crops and a larger geographical region, the timing of the procurement operations (which are often delayed and too short for farmers to benefit) and in some cases in the prices offered, which may not be adequately remunerative. That is why any perception that even the current inadequate regime of procurement may be dismantled stirs protest from an already beleaguered farming community.

(This article was originally published in the Business Line on September 20, 2021)