NATO geopolitical strategy has now joined the ‘coalition’ of Western geoeconomic forces accelerating planetary heating,…

How Dynamic is Global Capitalism? C. P Chandrasekhar and Jayati Ghosh

Capitalism is supposed to be all about economic growth, through the dynamism that is created by competition. This growth is meant to be driven by investment (or accumulation) which in turn is used to justify the shares of national income that are delivered to private profits, to the owners of capital. “Accumulate, accumulate! That is Moses and the prophets” famously said a certain Karl Marx in the first volume of Capital more than 150 years ago. It is undeniable that investment is the fundamental driving force of capitalism.

Of course, there have been and continue to be many naysayers, who object to this obsession with economic growth at all costs. There are obvious problems with using GDP as the basic indicator for even material well-being, and for all the important processes and outcomes that are important for human life. GDP does not capture human well-being, and can even disguise adverse outcomes. Per capita income is a poor estimate of general welfare when there are pervasive and growing economic inequalities. Many dimensions of human life that economies are supposed to provide a frame for, are ignored in this perspective.

But within the terms set by market-driven profit orientation, GDP is what matters, since capitalism is really concerned only with whatever is commercialised. Investment, the associated technological progress and the resulting expansion of economic activity are the most important metrics by which capitalist systems are judged. Never mind that this has been compared to the “grow-at-all-costs-and-in-all-circumstances” proclivity of cancer cells. To judge capitalism on its own terms, look at investment and monetary incomes.

Based on these (admittedly limited) indicators alone, how has capitalism been doing in its triumphal “globalised” phase? Remember that this is the period (beginning with the 1980s but really gathering force from the 1990s) when global capital managed to reduce if not eliminate almost all restrictions and regulatory constraints on its activities; when it was able to lobby for and put in place an international institutional and legal architecture that blatantly privileges its own interests over those of societies and the people who live in them and their human rights, as well as over nature and the preservation of the earth. New forms of ownership were strengthened, like intellectual property rights, that enabled monopolies of knowledge that in turn created other monopolies and forms of surplus extraction. Public sectors across the world were eroded and states withdrew from the provision of important physical and social infrastructure, amenities and social services, thereby leaving the field open for profit-making private activity. Tax rules led to reduced rates and loopholes that enabled multinational corporations and very rich people to pay very little tax, even when their profits and wealth soared.

Therefore, the past three decades should have experienced an explosion in private corporate activity: conditions have never been so favourable for large (and especially multinational) corporations. How did global capital respond to this immensely supportive configuration? Aggregate data at the global level on incomes and activity are necessarily subject to many concerns, but data from the World Bank’s World Development Indicators can still provide a rough idea.

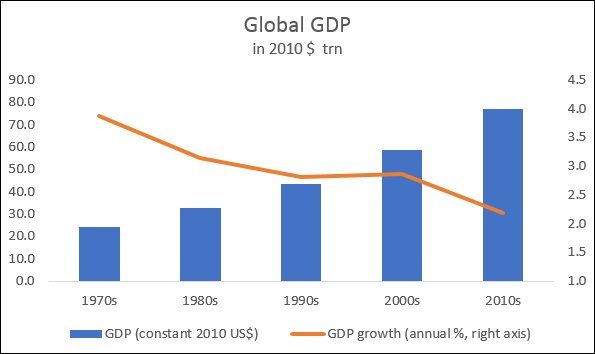

Figure 1: Global GDP growth has decelerated over past fifty years

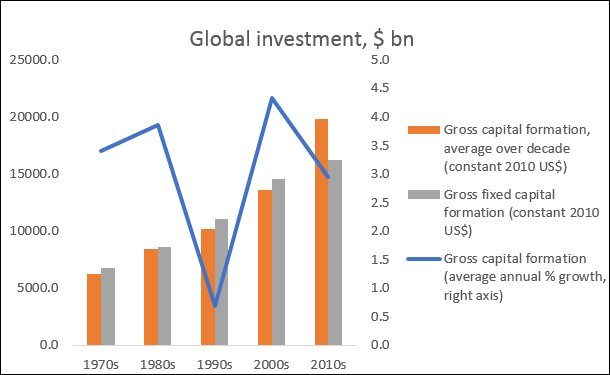

Note: In Figures 1 and 2, simple averages of the decade have been calculated.

Source for all figures: World Bank World Development Indicators online, accessed on 4 Sep 2021.

Figure 2: Global investment growth has been volatile

Note: Gross capital formation can be less than gross fixed capital formation if change in stocks is negative

Figure 1 indicates that average rates of growth have been declining over the half-century considered here. Figure 2 suggests that average investment rates (gross capital formation as per cent of GDP) plummeted in the first decade of the current globalisation, the 1990s, while the recovery of the 2000s reflects the low base effect. In the 2010s, Gross capital formation grew much faster than gross fixed capital formation, suggesting that there was more stockholding of machinery and equipment or increase in assets held as stores of value. Overall, the performance was not significantly better than the “stagflationary” 1970s or the crisis-ridden 1980s. Note that this was despite all the regulatory and other changes that so comprehensively tilted the playing field in favour of large private capital.

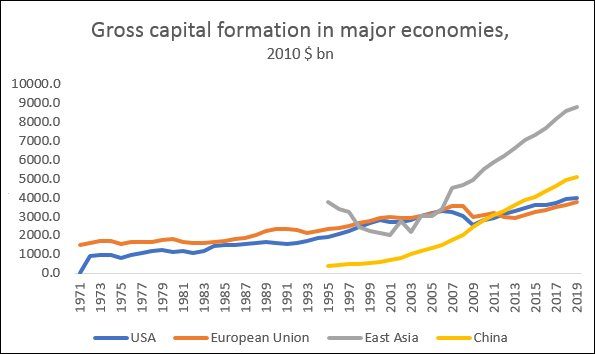

What is more, even the apparent recovery of global investment from 2000 onwards has really been due to the emergence of new kids on the block, specifically in East Asia. Figure 3 show that East Asia (for which WDI data are only available from 1995) became really significant in terms of investment in the 2000s, equalling both the USA and the European Union. After 2007, China’s capital formation soared well beyond that of these other two major capitalist economies. The force behind that rise of East Asian investment was China, which alone accounted for 77 per cent of the increase in East Asian gross capital formation between 2007 and 2019.

Figure 3: East Asia dominated investment in the past two decades

This regional shift could be interpreted as another example of the inherent dynamism of capital, such that when the richer and more advanced regions show signs of saturation of growth, capital moves to newer, lower-income geographical areas. This then allow these newer areas to expand rapidly. That is very much what is argued by the proponents of neoliberal globalisation, arguing that the very success of China shows the inherent possibilities for income convergence under neoliberal globalisation.

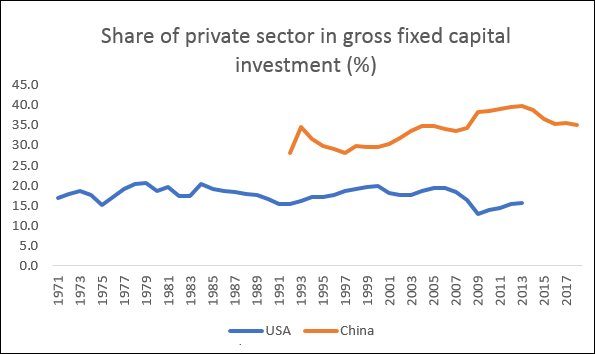

But that argument assumes that it is really private capital that is doing the heavy lifting, in response to all the liberalisation, deregulation and other policy changes that have eased its functioning and greatly increased its bargaining power. It turns out that the opposite is true. WDI data provide private shares of investment (for gross fixed capital formation) for some countries, and those for the USA and China are particularly revealing.

Figure 4 shows that throughout this entire period, private capital provided only the smaller part of gross fixed capital formation in these two economies. Surprisingly, the share of the private sector investment in total fixed capital investment was even smaller in the USA, at less than one-fifth, compared to China at just under 30 per cent. In other words, most of the fixed investment so crucial for capitalist accumulation and economic growth was undertaken by the public sector in these two most significant economies.

Figure 4: Private capital provided smaller shares of fixed investment in both the USA and China

This is really quite an extraordinary pattern, which completely confounds the general perception of private accumulation being the driving force of economic expansion during the phase of globalisation. At least in the two largest economies in the world, it was actually public investment that was far more weighty and substantial in fixed capital formation, accounting for more than four-fifths of total fixed capital formation in the USA and more than two-thirds in China.

This underlines the fact that global capitalism is on life support provided by governments. Not only is central bank intervention through massive creation of liquidity now essential even to maintain economic functioning in the advanced economies, but even the investment that does occur is mainly because of public sector activity, with private investment playing at best a supporting role. Purely on its own terms, global capitalism is failing.

(This article was originally published in the Business Line on September 7, 2021)