The weaponization of tariffs by US President Donald Trump has clearly generated fear and loathing…

The Prospect of a Telecom Monopoly C. P. Chandrasekhar and Jayati Ghosh

With its gross debt as of March 31, 2021 placed at Rs. 1.8 lakh crore and losses in the preceding quarter totalling more than Rs. 7,000 crore, Vi (former Vodafone Idea), once India’s largest telecom company in terms of subscriber base, is staring at bankruptcy. In a last-ditch effort to win state support to survive, Kumar Mangalam Birla, the Chairman of Vi, wrote to the government in June, offering to hand over the Aditya Birla Group’s close to 27 per cent stake in Vi. He later also stepped down as Chairman of Vi, as if to show his offer was credible.

The ‘shares for free’ offer was contingent on an official rescue package that would include revisiting the company’s adjusted gross revenue (AGR) liability, announcing a moratorium on spectrum charges and getting the regulator to set floor telecom tariffs above the low levels to which they had fallen because of the predatory price war launched by Reliance Jio. The company’s debt included spectrum payment obligations exceeding Rs 96,000 crore, AGR dues of close to Rs. 61,000 crore and debt to banks and financial institutions of around Rs. 23,000 crore. A reprieve on payments in the first two of these liabilities gives the company a fighting chance to remain in business.

Birla is clearly attempting to toss the ball into the government’s court, making the latter at least partly responsible for addressing the problems that a Vodafone closure would create for the company’s close to 280 million current telecom subscribers. Moreover, if all these subscribers migrate overnight to rivals Airtel, Reliance Jio and the public sector MTNL-BSNL combine, service quality is bound to be adversely affected for all subscribers. The government would not want that and would be under some pressure to respond.

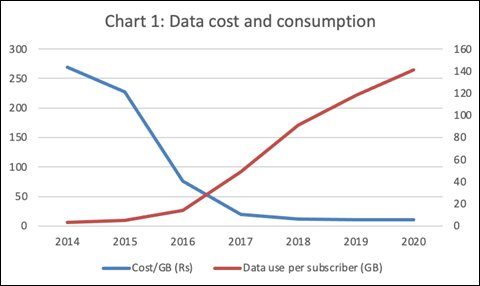

For the government the concern is the credibility of the post-reform telecom policy, which has been through many iterations over the years. Opening up the telecom sector to private operators is seen as a success for at least three reasons. First, it has given the government huge revenues in the form of license fees and spectrum charges, partially helping to mitigate its fiscal crisis. Second, telecom service tariffs have fallen dramatically (Chart 1), with data tariffs among the lowest in the world and voice traffic riding on data for free. Third, despite still pervasive digital inequalities, India’s telecom subscriber base and data consumption have increased dramatically. The industry’s subscriber base has more than doubled from 562 million in end December 2009 to 1.2 billion in May 2021.

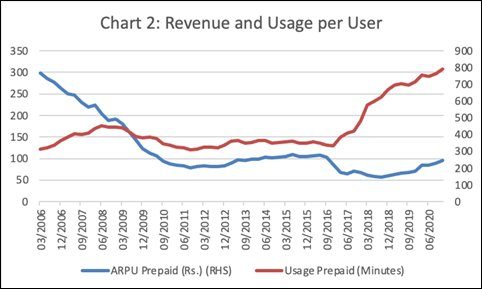

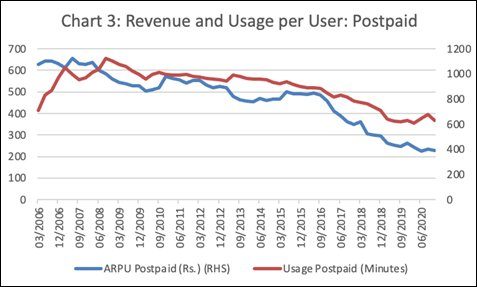

These ‘successes’, however, are also the source of the government’s problem. The competition among private operators to get a foothold in the telecom market meant that on the one hand they bid huge sums to win limited licences and scarce spectrum, and on the other joined a price war to win subscribers. The tariff decline became precipitous after Reliance Industries (which was earlier excluded from the telecom sector because of the terms of the empire split between the feuding Ambani brothers) entered the business through Jio in 2016. Reliance Jio had huge financial clout and did not have legacy problems like installed earlier generation technologies and disputed AGR dues that had accumulated over the years. It launched a predatory price war to quickly win and expand market share, which led to falling average revenue per user (ARPU) (Charts 2 and 3). Tariff cuts neutralised the gains in terms of subscriber base and usage triggered by those cuts.

The net result of the combination of high licence and spectrum costs and low revenues was that investments in telecom infrastructure lagged, affecting the service quality of incumbent providers. But more importantly, the industry experienced continuous shakeout, with the number of operators shrinking to effectively three in the private sector (Airtel, Jio and Vi) and two in the public sector. The potential exit of Vi signals that the shakeout is still not over.

A corollary of this is growing concentration in the industry. In the last quarter of 2009, the three top players in the industry—Bharti Airtel, Vodafone and the Anil Ambani led Reliance Communications—accounted for 54.8 per cent of subscribers. That proportion fell subsequently but remained above 50 per cent till quarter ending December 2015. But then a dramatic transformation began. First, Reliance Communications exited from the market because it was bleeding losses and was part of a group suffering attrition. Second, Vodafone’s merger with Idea in 2018 saw the subscriber base of the then second largest player in the industry jump from 213 million to 419 million between 2012 and 2018, making it the leading player in terms of subscriber numbers. Finally, Jio’s entry into the market and its price-war-led scorching pace of expansion made it part of the top three, with a steep rise in its subscriber base from 72 million at the end of 2016 to 439 million in May 2021.

As a result, the subscriber share of the top three players rose from 49 per cent at end 2016 to 89 per cent in May 2021. Three-fourths of that 40 percentage point increase in the subscriber share of the top three was on account of Reliance Jio. Its share rose from 6.3 per cent at end 2016 to 36.3 per cent in May 2021, well above Airtel’s 29.5 per cent share, making it the dominant player.

This rapid rise in Jio’s market share is unlikely to taper off, with more subscribers released by Vodafone’s exit. The battle for market shares could well continue, and as of now Reliance Jio has much deeper pockets. That can affect the relative pace of deployment of 5G technology, with implications for future market shares. Strapped for funds because of AGR dues and spectrum payments, Bharti Airtel has called for a hold on 5G spectrum auction, since it cannot lay out the infrastructure fast enough. Not surprisingly Sunil Mittal, the Chairman of Bharati Airtel is supporting Vi’s plea for state support, possibly hoping that the government would give in to the three demands of Birla on AGR dues, spectrum payments and a floor tariff, to prevent the aggressive growth of Reliance Jio from pushing Airtel down as well.

If Reliance does exploit its current position of strength to establish a near monopoly position in the market, there are several challenges it can pose. The least of them is a sharp rise in tariffs in the medium-term, adversely affecting consumers. More important is the control that Jio would establish over the flow of data. Reliance Industries is a conglomerate that has diversified into areas from e-commerce to providing various digital services, including cinema, news, music and retail. If the parent company has a monopoly over the pipe through which those services are delivered, there are multiple ways in which it can stifle the competition.

Monopoly is no more a question of pricing to generate superprofits at the expense of the consumer. It is the ability to stamp out the competition and prevent entry in sunrise sectors by using dominance in an existing one. That is the strength of platforms such as Amazon, Google and Facebook. With control over the means through which data is delivered, Reliance will also acquire powers that can stifle the competition. It is to be seen whether the government would step in to stop that.

(This article was originally published in the Business Line on August 23, 2021)