The weaponization of tariffs by US President Donald Trump has clearly generated fear and loathing…

Is Emerging Asia in Retreat? C. P. Chandrasekhar and Jayati Ghosh

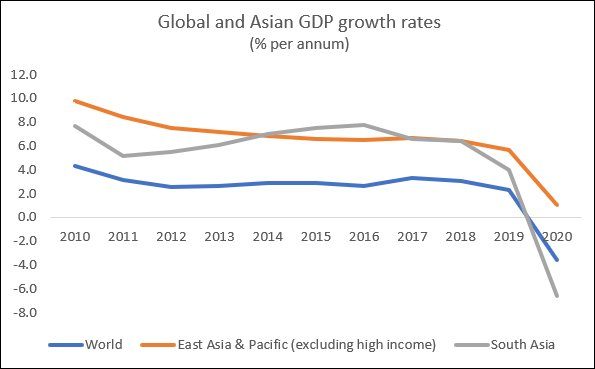

International observers still view Asia—and particularly East Asia—as the most dynamic economic region in the world, a perception that has been even more entrenched over the period of the pandemic. Certainly, if aggregate GDP growth rates in real terms (as shown in Figure 1) are anything to go by, there is no doubt that the region of East Asia has been growing faster than the world as a whole, and has even managed to maintain positive growth in the pandemic year 2020, when most other regions have stumbled or even collapsed. By contrast, South Asia, which earlier showed higher growth rates, was decelerating even before the pandemic and has since shown a worse decline than the world as a whole.

Figure 1: East Asia has performed better than the world economy as a whole

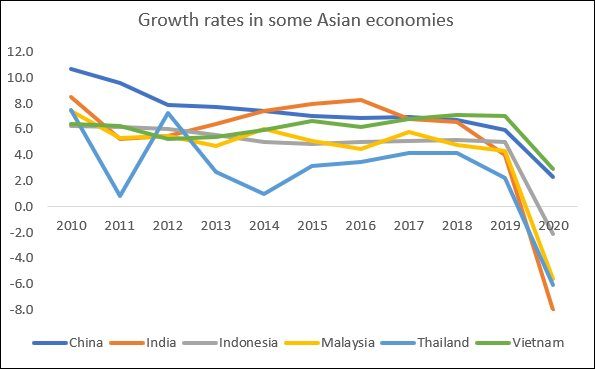

However, aggregate East Asian achievement has been hugely coloured by China, which now dominates the region in absolute size and in growth performance. China accounts for more than half of the overall expansion of incomes in the region (at market exchange rates). Furthermore, as Figure 2 indicates, China and Vietnam are outliers among other prominent “emerging market economies” in Asia, in terms of maintaining relatively high growth rates and also avoiding GDP declines in the pandemic year. The other economies illustrated in Figure 2, which are among the larger economies and the most favoured destinations for global finance capital, have not fared so well.

Indeed, the past decade shows significant deceleration in GDP growth for these economies even before the pandemic so drastically disrupted economic activity. Clearly, it is fallacious to judge the performance of Asian economies by being overly focussed on China, which is exceptional in many ways and cannot be taken as representative of the rest of the region. In India, growth rates of GDP fell from 8 per cent in 2016 to 4 per cent in 2019, and even these rates are widely considered to be overestimates. In Thailand the decline was from rates in excess of 7 per cent at the start of the decade to only 2.3 per cent in 2019; in Malaysia the decade began with 7.4 per cent growth which fell to 4.3 per cent in 2019. In Indonesia the decline was minor, from 6.2 per cent in 2010 to 5.0 per cent in 2019.But only Vietnam shows a steady rate of expansion of 6-7 per cent per annum before the pandemic, and thereafter was the least affected economy in 2020.

Figure 2: There was growth deceleration even before the pandemic

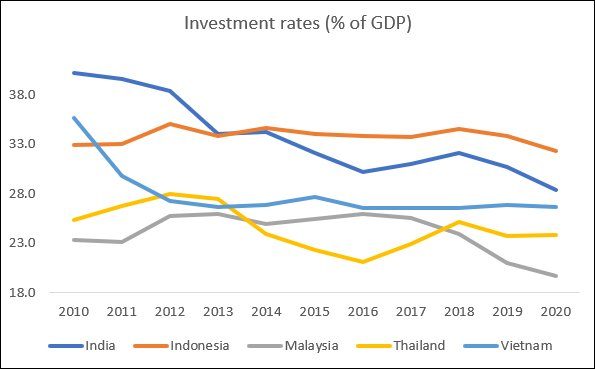

Figure 3: Investment rates declined in some economies

So why was growth decelerating over the previous decade? One obvious reason is the fact that investment rates were declining, as Figure 3 indicates. The sharpest decline over the decade was in India, where investment rates fell from around 40 per cent to around 30 per cent. While Malaysia and Indonesia showed less dramatic declines in this period, their big shift had already occurred from 1998, after the Asian Financial Crisis that led to a sharp reduction, of between one-quarter to one-third, in their investment rates. In Malaysia this plummeted further to 19 per cent by 2019, while it remained stable in Indonesia. Vietnam too showed greater stability of the investment rate.

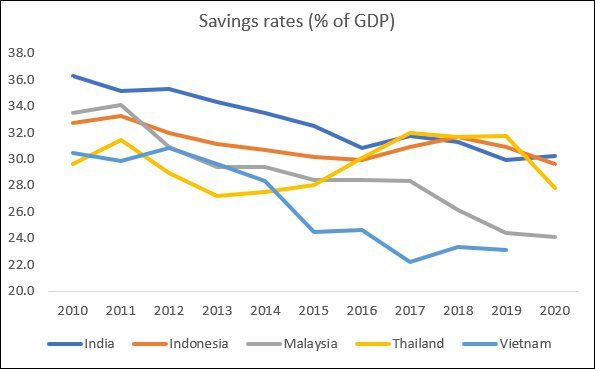

It was argued by then US Federal Reserve Chairman Ben Bernanke in 2005 that Asian economies were characterised by a “savings glut”, and this argument was revived by the American economist Brad Setser in 2016. Yet, if we exclude China from this discussion, what is striking is how savings rates also came down in these economies over the past decade. Once again, this was clearly a pre-pandemic tendency, which was obviously substantially worsened by the pandemic. So it is hard to sustain the idea of a savings glut for these countries; the problem rather is that investment rates fell even more than savings rates.

Figure 4: Savings rates also declined

Of course, this begs the question of why savings and investment rates were coming down at all. After all, these economies—especially India, Indonesia, Malaysia and Thailand—had undertaken substantial internal and external financial liberalisation precisely to encourage more domestic financial savings by avoiding “financial repression” and opened up capital accounts to unregulated financial flows in order to attract more financial resources for foreign investment. So what happened?

The story is really that external financial liberalisation in a context of apparently strong export performance (of either goods or services) made emerging markets in Asia—of which these are some of the most prominent but not the only ones—become the objects of desire of global finance. But given the hierarchy of markets and currencies that characterise the world of mobile capital flows, this was not enough to ensure sustained net inflows of capital that could be used to increase domestic investment for development purposes. Rather, there were periodic swings and reversals of gross inflows. This made governments in the region so concerned about possible adverse financial market responses to proactive fiscal policies that they limited their own capacities for fiscal stimulus during downswings, including in the current pandemic.

Even more significantly, gross outflows of capital that were enabled by the capital account liberalisation also grew and became very large. As a result, net inflows of capital were much small than gross inflows, and for some countries like Malaysia, even negative. And the rates of return on financial assets held abroad (whether by central banks or private investors) were significantly lower than the rates of return on financial assets inside the economy held by non-residents. This led to very significant “seignorage” losses every year (losses driven by the difference in returns on inbound and outbound capital flows). In Thailand, for example, these amounted to as much as 5.2 per cent of GDP each year in 2010-18—significantly more than the net inflow of capital!

Even when there were net capital inflows, as in India and Indonesia, these did not translate into increased domestic investment or enable domestic investment in desired sectors. Instead, central banks added to forex reserves for “self-insurance” against possible capital flight, and to manage the exchange rates in the face of the substantial and often volatile capital movements.

Ironically, therefore, the financial liberalisation that was meant to provide more resources for domestic investment in emerging markets has led to exactly the opposite pattern. As advanced economies recover from the pandemic faster than anticipated, this is going to lead to tighter global capital markets, with potentially serious consequences for emerging markets, including the Asian economies that have hitched their policy wagon to this uncertain star.

(This article was originally published in the Business Line on July 12, 2021)