Output and productivity growth slowed in Southeast Asia after the 1997 financial crisis. Latin America…

The Inadequate Food Safety Net C. P. Chandrasekhar and Jayati Ghosh

With India experiencing a severe second wave of the Covid-19 pandemic, forcing decentralized lockdowns, a crisis of loss of jobs and livelihoods and resulting hunger is being reported from across the country. A reluctant central government has, therefore, been forced to revive the Pradhan Mantri Garib Kalyan Anna Yojana (PMGKAY), to distribute 5 kilograms of free foodgrain per person per month to the approximately 80 crore beneficiaries covered under the National Food Security Act (NFSA). The reluctance shows in the decision to introduce the scheme only for a two-month period (May-June 2021) and to ignore demands for a significant hike in the free quota or to address exclusion of large numbers who need the support. As of now, there is no reason to believe that the second wave of the pandemic will fully abate, and normalcy will be restored, by July 2021. But the government has obviously decided to keep its commitment to free food provision to the minimum.

In its own reading, the PMGKAY has been the leading component of the government’s safety net over this period. In 2020-21, the scheme was announced initially for three months (PMGKAY-I April-June 2020) and then extended for a further five months (PMGKAY-II July-November 2020), though the effects of the economic devastation wrought by the pandemic and the lockdown lasted much longer. According to the Ministry of Consumer Affairs, Food and Public Distribution, a total of 305 lakh tonnes of foodgrains (104 lakh tonnes of wheat and 201 lakh tonnes of rice) were allocated for this purpose in 2020-21.

Besides the fact that there are many eligible persons who are excluded from coverage under the NFSA and some like migrant workers could not access its benefits, survey evidence suggests that the free food provided under the PMGKAY did not adequately address the hunger that resulted from the devastating impact of the unemployment and loss of livelihoods that resulted from the harsh lockdown imposed during the first wave of the pandemic. Many experts had suggested that, besides the special allocation under PMGKAY, the government should rovide the regular entitlement of subsidized food provided under the NFSA to those covered (35 kg per family per month for severely poor Antyodaya Anna Yojana beneficiaries and 5 kg per person per month for the rest) free of cost, and widen coverage through universal provision. Those recommendations were not accepted.

The free foodgrains scheme was not limited in scope by shortage of physical stocks. With India having been the beneficiary of two good monsoons in succession, with a third predicted, agricultural output is at record levels. Rice output rose from 109.7 million tonnes in 2016-17 to 112.8 million tonnes in 2017-18, 116.42 million tonnes in 2018-19, 118.9 million tonnes in 2019-20 and an estimated at 121.5 million tonnes in 2020-21. The corresponding figures for wheat are 98.5, 98.9, 102.2, 107.9 and 108.8 million tonnes respectively.

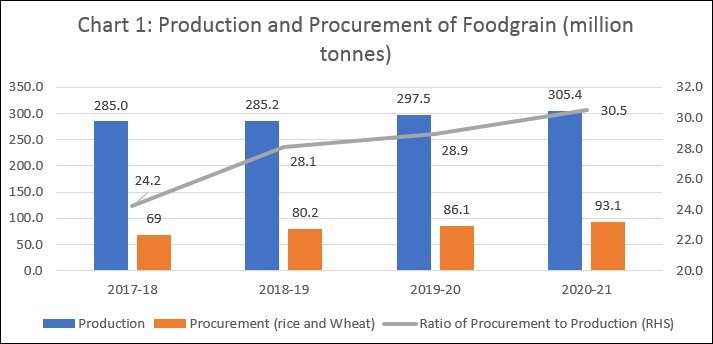

The result of this production surge was higher procurement and larger stocks with the government. As Chart 1 shows, total foodgrain production rose from 285 million tonnes in 2017-18 and 2018-19 to 297.5 million tonnes in 2019-20 and 305.4 million tonnes in 2020-21. Procurement of rice and wheat rose from 69 million tonnes in 2017-18 to 93 million tonnes till end-May in marketing season 2020-21, when there were still a few months of the rice marketing season left to complete. Not only was production rising, but the share of production procured recorded an increase.

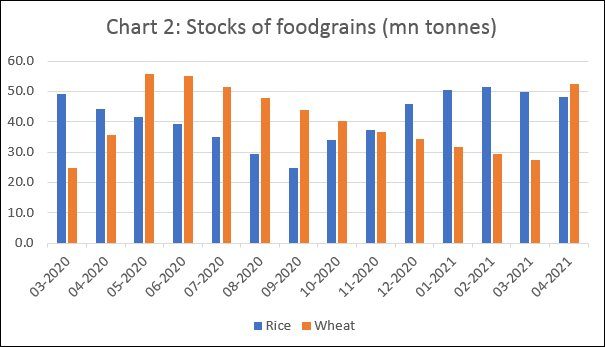

The net result was a surfeit of grain in the godowns of the FCI and other agencies. As compared with the norm of 13.6 million tonnes of rice and 7.5 million tonnes of wheat required as buffer stocks (operational and strategic) on April 1 of a year, actual stockholding in April 2020, when the pandemic’s effects began to be felt, was much higher. Stocks of rice were at 44.2 million tonnes and that of wheat at 35.8 million tonnes. As Chart 2 shows, foodgrain stocks did fall,, as is to be expected, after May 2020 because of allocations under the NFSA and the PMGKAY, with rice stock levels touching their lowest in September 2020 and wheat in March 2021. However, stocks remained well above buffer stocking norms, and rose subsequently. In October 2020, as compared with buffer requirements of 11.3 million tonnes of rice and 20.5 million tonnes of wheat, stocks amounted to 34 million tonnes of rice and 40.3 million tonnes of wheat. This was a month before both phases 1 and 2 of the PMGKAY were complete. Pre-existing stocks were not wiped out, and stock levels were being replenished with new procurement.

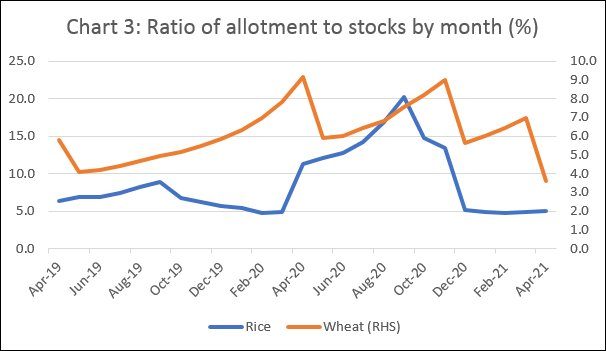

That the government was not maximizing its access to excess stocks in its godowns was also clear from trends in the ratio of allotments under the NFSA and PMGKAY to the level of stocks. Chart 3 depicts the ratio of foodgrain allotments both under the regular NFSA scheme and the PMGKAY to the stock level by month. While the ratio of allotment to stocks did move up, especially in the case of rice, after the launch of the PMGKAY, the highest that ratio touched was 20.2 per cent in the case of rice in September 2020 and 9.2 per cent in the case of wheat in April 2020. Between April and November 2020, when the PMGKAY was being implemented that ratio averaged 14.4 per cent in the case of rice and 7.4 per cent in the case of wheat. The comparable figures for the corresponding months of 2019 were 7.8 per cent and 4.8 per cent respectively. In terms of availability of physical stocks, the headroom for enlarging the free food scheme in terms of coverage and quantum was substantial.

Part of the explanation for the government’s unwillingness to deploy surplus stocks through an expanded and universal free grain distribution scheme is its regressively conservative commitment to curtailing subsidies, including food subsidies, in its budget. The subsidy bill for PMGKAY I is estimated at Rs. 46,061 crore and that for PMGKAY II at Rs. 76,000 crore, taking the total subsidy for the PMGKAY in 2020-21 to Rs. 1.49 lakh crore. That amounts to just 0.8 per cent of estimated GDP for that year. The subsidy needed to support the regular allocation under the NFSA and other ongoing schemes is Rs. 1.80 lakh crore over the whole year, or 0.9 per cent of GDP. If the regular NFSA allocation had also been made free-of-cost for the whole year, the additional subsidy incurred would not have been large. Moreover, since the FCI is saddled with excess stocks, disposing of them through the PMGKAY would have saved the government the carrying costs it would have otherwise incurred. Given the crisis, the case for enhancing subsidies is strong. But fiscal conservatism and political indifference have meant that the effort to redress hunger among those deprived of livelihoods in the aftermath of the crisis was and remains woefully inadequate.

(This article was originally published in the Business Line on June 1, 2021)