Liberal opinion holds that the international monetary and financial system is a device for promoting…

The Hunger Pandemic C. P Chandrasekhar and Jayati Ghosh

The disease ripping through the country is only one of the destructive forces affecting the lives of hundreds of millions of Indians. The dramatic increase in hunger is another. Like devastation wrought by the current surge in coronavirus infections, this too is the result of policy failure and official callousness. It is already causing immense suffering among affected people and will have serious repercussions on their future health and physical resilience.

Everyone knows that the brutal national lockdown imposed in March 2020 and the subsequent economic collapse led to loss of livelihood among people who had little or no ability to withstand such a shock. Official “relief” measures were so minor compared to the need that they could only provide a drop in the ocean for crores who faced falling incomes and inability to meet their basic needs. The provision of 5 kg free food grain rations per month to NFSA card holders from April to November barely touched the surface of the problem, even as it excluded at least 100 million people who were not part of NFSA lists.

Yet the full extent of the humanitarian catastrophe was possibly still not evident to most commentators, without data to indicate how food consumption had actually been affected. A new report from Hunger Watch, based on a survey of 3994 households conducted over 11 states in October 2020, provides a horrifying picture. The survey was purposively designed to cover weaker sections of the population, with 79 per cent of respondents having household income of less than Rs 7,000. This is broadly representative of the population, but also captures the group that relief measures should seek to benefit.

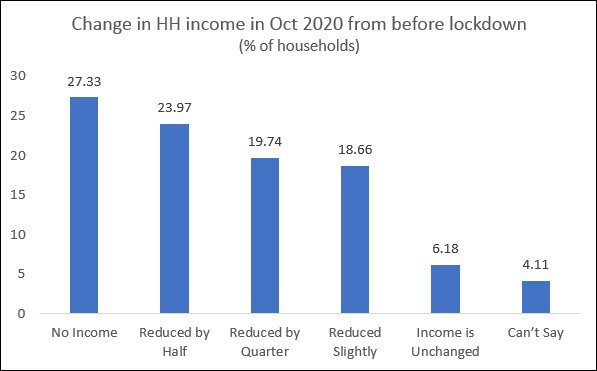

The survey provides stark evidence of the degree to which basic material conditions and access to food had worsened by October 2020. The survey report is very rich and contains a wealth of data, but some of the more important points deserve to be highlighted. First, as shown in Figure 1, almost all households reported falling income – only 6 per cent said their income had not changed while another 4 per cent could not say. 27 per cent of households had no income at all over the period from the start of the lockdown to October 2020, while for another 24 per cent their incomes had halved. Income declines of this severity are nothing less than catastrophic.

Figure 1

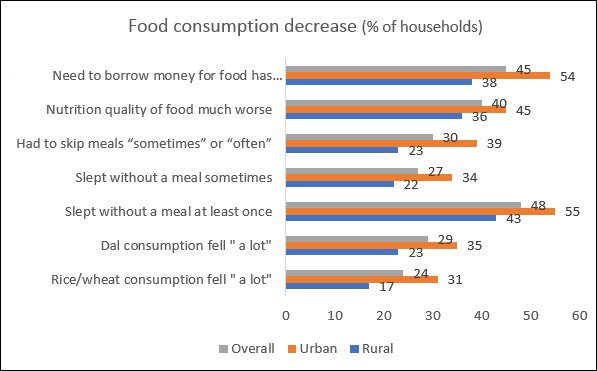

Figure 2

With such widespread income loss, it is hardly surprising that there were significant declines in food consumption. Figure 2 shows how consumption of basic cereals declined “a lot” for around one-fifth of the population, and nearly half the sample slept without a meal at least once, while skipping meals “sometimes” or “often” was also significant. Urban areas showed more widespread declines, as all food has to be purchased. Both quantity and quality of food intake were affected: the nutritional quality of food intake clearly suffered, becoming “much worse” for 40 per cent of the sample and “worse” for another 45 per cent. More detailed data in the report suggest that declining intake was especially evident for meat/fish/eggs, pulses and fresh vegetables.

An especially worrying feature of food insecurity apparent from the Report is that it was even greater among socially vulnerable groups that were specially identified. Table 1 shows that this was true for almost all of the defined vulnerable categories, with some (like survivors of domestic violence, Scheduled Castes, Particularly Vulnerable Tribal Groups and Muslims) experiencing particularly sharp declines.

Table 1: Food insecurity among vulnerable groups

|

Single women headed HHs |

HHs with disabled person |

Older persons without caregivers |

Survivors of domestic violence |

Trans gender and sexual minorities |

SCs |

STs |

Particularly Vulnerable Tribal Group |

Muslims |

|

|

Rice/wheat consumption fell “a lot” |

28 |

21 |

32 |

46 |

7 |

30 |

13 |

22 |

31 |

|

Dal consumption fell “a lot” |

35 |

24 |

39 |

44 |

7 |

35 |

18 |

37 |

34 |

|

Slept without a meal at least once |

56 |

44 |

58 |

60 |

22 |

51 |

37 |

54 |

60 |

|

Slept without a meal sometimes |

31 |

24 |

36 |

35 |

11 |

36 |

17 |

13 |

33 |

|

Had to skip meals “sometimes” or “often” |

33 |

22 |

42 |

42 |

15 |

40 |

20 |

34 |

37 |

| Nutrition quality of food much worse |

11 |

13 |

13 |

12 |

4 |

9 |

20 |

9 |

6 |

| Need to borrow money for food has increased |

48 |

41 |

43 |

50 |

27 |

59 |

34 |

45 |

54 |

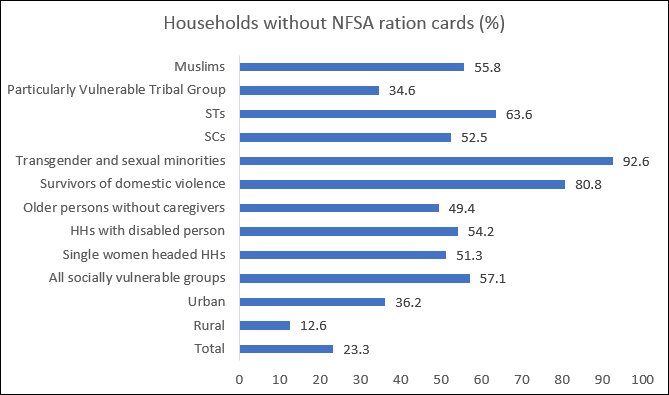

Figure 3

The Pradhan Mantri Garib Kalyan Anna Yojana (PMGKAY) which was announced as a relief measure in April 2020 to provide 5 kg of free rations per month, was extended until November 2020. However, only those with NFSA ration cards were eligible to receive these free rations. Figure 3 shows that only 43 per cent of the respondents had NFSA ration cards to access these free grains under the PMGKAY. 27 per cent of the respondents had ration cards providing subsidised grains under various state schemes, but states would have had to provide free grain additionally on their own. Shockingly, 23 per cent of respondents had no ration cards at all (36 per cent in urban areas and 13 per cent in rural areas). Therefore, the estimates of exclusion from the NFSA are confirmed, with dire consequences.

Note that this was well before the second wave of Covid-19, at a time when the number of cases was falling from the first peak of September 2020. The disastrous second wave is now sweeping over a population already enfeebled over the past year, forced to be “self-reliant” by rulers denying the most basic social protection.

In this context, it is clear that the Supreme Court judgement of 13 May, directing the Centre and the state governments of Punjab, Haryana and Uttar Pradesh to provide free rations without insisting on ID proof to all migrant workers and to run kitchens providing free meals twice a day, is both necessary and welcome. But it does not go far enough. Hunger is now widespread, and not only among migrant workers. Basic provision of free food grain without requiring ID must now be provided across the country, and it must be accompanied by direct cash transfers of at least Rs 7000 per month for three months, to compensate for more than a year of lost livelihood. Without these most basic measures, the health crisis is being compounded by a hugely damaging hunger crisis.

(This article was originally published in the Business Line on May 18, 2021)