Donald Trump’s tariffs have disrupted supply chains, roiled global markets, and escalated the trade war…

Asia’s Post-pandemic Encounter with Foreign Finance C. P. Chandrasekhar and Jayati Ghosh

It is by now a much-repeated story. Despite the devastation wrought by the Covid-19 pandemic, punters in global financial markets have had a field day. If there is one location where the pandemic has not been able to wreck damage, it is the market for equity and bonds worldwide. This has been true in Asia in general, and in India, as well. Having initially suffered a hit at the end of the first quarter and beginning of the second quarter of 2020, when the virulence and implications of the pandemic began to be recognized, markets soon recovered. However, evidence from Bloomberg on four representative emerging markets in Asia (India, Indonesia, the Philippines and Thailand) suggest that there have been significant differences in market trends in Southeast Asia, on the one hand, and India, on the other (Chart 1).

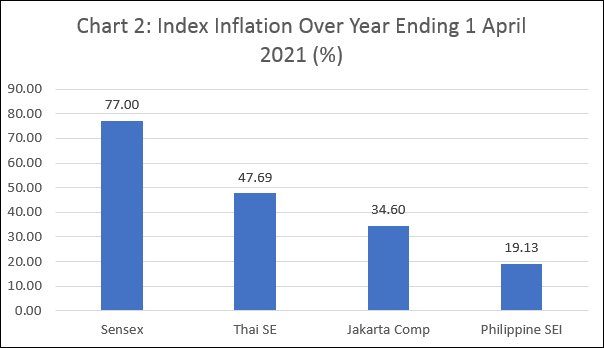

While a market recovery in Indonesia, the Philippines, and Thailand was visible in 2020, a year after the immediate post pandemic market collapse in March 2020, leading stock market indices in these countries had not returned to their pre-pandemic levels. In India, on the other hand, not only had the recovery been much sharper, but the benchmark Mumbai Sensex signalled that bullish trends had contributed to a heady boom. Over the year ending April 1 2021, while benchmark composite indices rose by 19 per cent in the Philippines, 35 per cent in Indonesia and 48 per cent in Thailand, the rise was a staggering 77 per cent in India, which experienced one of the sharpest real economy contractions in economic activity over that period (Chart 2). As Chart 1 shows, Mumbai broke away and widened its lead relative to the others in the months after June 2020. A collapse and subsequent recovery was the common pattern, but the similarity ended there, with the bulls trading in Mumbai willing to place larger bets and for longer.

There is a consensus among market observers that, irrespective of the explanations advanced for short term fluctuations, medium term, financial market exuberance in emerging and developed country markets was driven by the availability of excessively cheap capital in international markets. When developed country central banks responded to the Covid-induced crisis by releasing large volumes of liquidity at near zero interest rates, even as the economy was clogged because of containment measures and lockdowns, this money found its way to financial markets. The result a huge divergence between real economy and financial market performance. The flow of capital was directed to emerging markets as well. So, the recovery of and boom in financial markets there is not too surprising. What needs understanding is the sharp divergence across similarly placed financial markets, as observed in Asia for example.

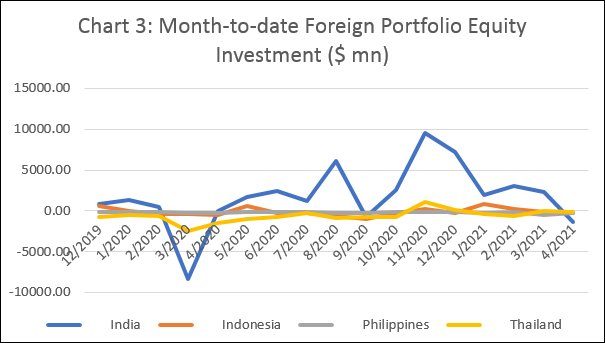

The proximate cause for this divergence was, as expected, differences in the volume of capital that flowed into these markets. As Chart 3 shows, monthly net inflows of foreign portfolio capital for investments in equity were on average significantly higher and far more volatile in India, than in Indonesia, the Philippines and Thailand. Thus, the average monthly inflow during May to August 2020 was $2.9 billion in India, whereas all three Southeast Asian markets recorded net outflows varying between $150 and $190 million in Indonesia and the Philippines and around $730 million in Thailand. What is more, over October 2020 to March 2021, average monthly portfolio capital inflows into India’s equity markets averaged a much higher $4.4 billion, whereas Indonesia recorded a small average inflow, and the Philippines and Thailand small net outflows. Thus, it does appear that in the case of the Southeast Asian countries the market’s recovery and subsequent buoyancy was driven by flows into the principal stocks driving their indices, with aggregate net flows small or negative, whereas India was the beneficiary of large net inflows that set off its sharp boom.

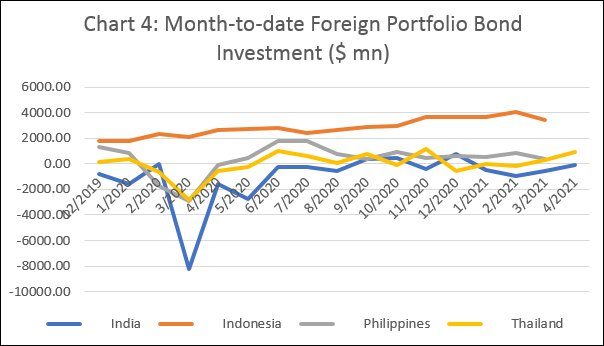

Remarkably, in India’s case, the flow of capital into equity was at the expense of portfolio investments in bonds (Chart 4). Between March and May 2020, there was a net outflow of $4.2 billion from bonds, though between October 2020 and March 2021 the net outflow was a much smaller $200 million. However, Indonesia has over much of the last year recorded significant net inflows into bond markets, as has the Philippines, albeit of much smaller magnitude. Thus, financial investors in Indian markets appear to have adjusted their portfolios away from bonds to more speculative investments in equity.

Unlike the overall increased flow of investments into emerging markets, the cross-country differential in the magnitude and pattern of flows cannot be explained from the supply side. Access to cheap capital may have set off a search for yields in emerging markets, but the choice of how much is invested in each market and of the instruments to bet on must be influenced by local factors shaping perceptions on how markets would move.

Needless to say, these perceptions are fickle and hard to pin down. But there is reason to believe that Indian stocks (rather than bonds) were the flavour of the pandemic season because of investor conviction that the government in India will go out of its way to protect and drive up corporate profits. Besides the business-friendly image that the Narendra Modi government has cultivated throughout its tenure, it decided in September 2019, well before the pandemic and in the midst of a recession, to announce large corporate tax concessions that reduced the effective tax rate from close to 35 per cent to 22 per cent. The intent of the government to divest itself of most of its assets to provide the private sector more space to profit has also been made clear. And an announcement that the financial sector hitherto dominated by public sector units would now be transformed into a largely private domain has been made. The message seems to be that even if growth does not accelerate because the market remains constrained, the profit to be made from the available market would be increased manifold.

These are signals that punters cannot ignore, and they have not. But the consequence is that there has been a steep rise in India’s exposure to speculative foreign portfolio investment. The fear now is of a sudden withdrawal. The spending spree of the Biden administration aimed at pushing for a US recovery could set off inflation and an increase in interest rates triggering an exit of capital from emerging markets. India saw net withdrawals from equity of $1.4 billion in April, which is much more than the $250-260 million net outflow in Indonesia and the Philippines. Having been the target of disproportionate flows of capital in search of yields over the last year, India will lose much more heavily from any reversal of that flow. And the impact that the current surge in Covid infections would have on perceptions could be completely destabilising.

(This article was originally published in the Business Line on May 3, 2021)