Presenting new research, Dylan Sullivan and Jason Hickel mount a devastating critique of the impact…

Global Austerity Alert: Looming budget cuts in 2021-25 and alternative pathways Isabel Ortiz and Matthew Cummins

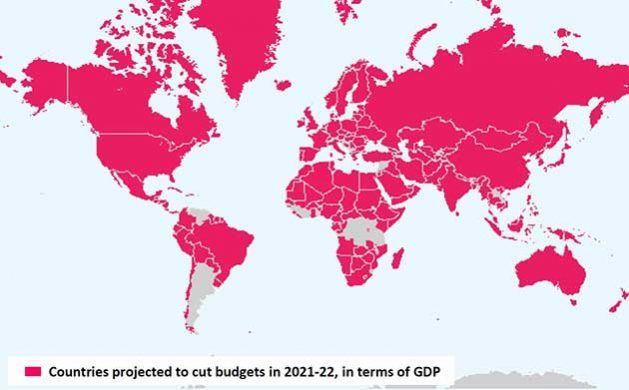

Map of countries with projected austerity cuts in 2021-2022, in terms of GDP, based on IMF fiscal projections. Credit: I. Ortiz and M. Cummins, 2021

Last week Ministers of Finance met virtually at the Spring Meetings of the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and the World Bank to discuss policies to tackle the pandemic and socio-economic recovery.

But a global study just published by the Initiative for Policy Dialogue at Columbia University, international trade unions and civil society organizations, sounds an alert of an emerging austerity shock: Most governments are imposing budget cuts, precisely at a time when their citizens and economies are in greater need of public support.

Analysis of IMF fiscal projections shows that budget cuts are expected in 154 countries this year, and as many as 159 countries in 2022. This means that 6.6 billion people or 85% of the global population will be living under austerity conditions by next year, a trend likely to continue at least until 2025.

The high levels of expenditures needed to cope with the pandemic have left governments with growing fiscal deficit and debt. However, rather than exploring financing options to provide direly-needed support for socio-economic recovery, governments—advised by the IMF, the G20 and others—are opting for austerity.

The post-pandemic fiscal shock appears to be far more intense than the one that followed the global financial and economic crisis a decade ago. The average expenditure contraction in 2021 is estimated at 3.3% of GDP, which is nearly double the size of the previous crisis. More than 40 governments are forecasted to spend less than the (already low) pre-pandemic levels, with budgets 12% smaller on average in 2021-22 than those in 2018-19 before COVID-19, including countries with high developmental needs like Ecuador, Equatorial Guinea, Kiribati, Liberia, Libya, Republic of Congo, South Sudan, Yemen, Zambia and Zimbabwe.

The dangers of early and overly aggressive austerity are clear from the past decade of adjustment. From 2010 to 2019, billions of people were affected by reduced pensions and social security benefits; by lower subsidies, including for food, agricultural inputs and fuel; by wage bill cuts and caps, which hampered the delivery of public services like education, health, social work, water and public transport; by the rationalization and narrow-targeting of social protection programs so that only the poorest populations received smaller and smaller benefits, while most people were excluded; and by less employment security for workers, as labor regulations were dismantled. Many governments also introduced regressive taxes, like consumption taxes, which further lowered disposable household income. In many countries, public services were downsized or privatized, including health. Austerity proved to be a deadly policy. The weak state of public health systems—overburdened, underfunded and understaffed from a decade of austerity—aggravated health inequalities and made populations more vulnerable to COVID-19.

Today, it is imperative to watch out for austerity measures with negative social outcomes. After COVID-19’s devastating impacts, austerity will only cause more unnecessary suffering and hardship.

Austerity is bad policy. There are, in fact, alternatives even in the poorest countries. Instead of slashing spending, governments can and must explore financing options to increase public budgets.

First, governments can increase tax revenues on wealth, property, and corporate income, including on the financial sector that remains generally untaxed. For example, Bolivia, Mongolia and Zambia are financing universal pensions, child benefits and other schemes from mining and gas taxes; Brazil introduced a tax on financial transactions to expand social protection coverage.

Second, more than sixty governments have successfully restructured/reduced their debt obligations to free up resources for development. Third, addressing illicit financial flows such as tax evasion and money laundering is a huge opportunity to generate revenue. Fourth, governments can simply decide to reprioritize their spending, away from low social impact investments areas like defense and bank/corporate bailouts; for example, Costa Rica and Thailand redirected military expenditures to public health.

Fifth, another financing option is to use accumulated fiscal and foreign reserves in Central Banks. Sixth, attract greater transfers/development assistance or concessional loans. A seventh option is to adopt more accommodative macroeconomic frameworks. And eighth, governments can formalize workers in the informal economy with good contracts and wages, which increases the contribution pool and expands social protection coverage.

Expenditure and financing decisions that affect the lives of millions of people cannot be taken behind closed doors at the Ministry of Finance. All options should be carefully examined in an inclusive national social dialogue with representatives from trade unions, employers, civil society organizations and other relevant stakeholders.

#EndAusterity is a global campaign to stop austerity measures that have negative social impacts. Since 2020, more than 500 organizations and academics from 87 countries have called on the IMF and Ministries of Finance to immediately stop austerity, and instead prioritize policies that advance gender justice, reduce inequality, and put people and planet first.

Isabel Ortiz is Director of the Global Social Justice Program at Joseph Stiglitz’s Initiative for Policy Dialogue at Columbia University, former Director at the International Labour Organization (ILO) and UNICEF

Matthew Cummins is senior economist who has worked at UNDP, UNICEF and the World Bank.

(This article was originally published in Inter Press service (IPS) news on April 17, 2021)