Donald Trump’s tariffs have disrupted supply chains, roiled global markets, and escalated the trade war…

Worrying spike in Global Food Prices C. P. Chandrasekhar and Jayati Ghosh

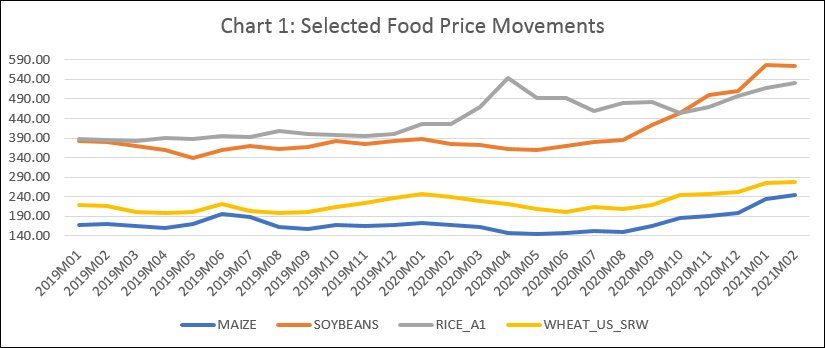

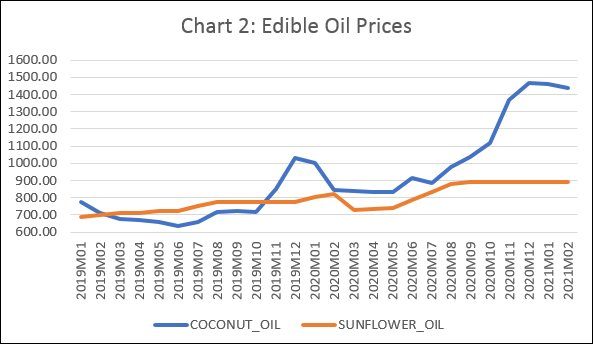

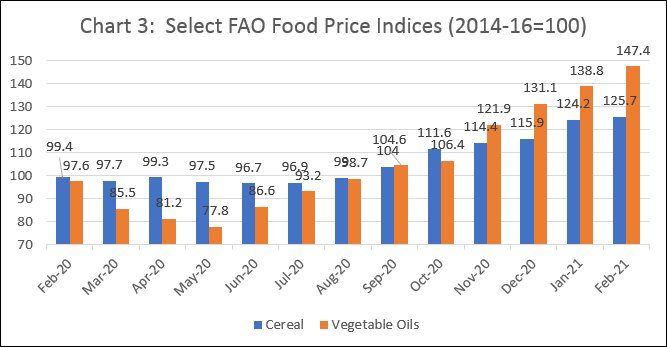

Having recovered from their lows touched early or mid-2020, food prices are rising fast. At $574.8 a metric tonne in February 2021, the price of soyabean was 53 per cent higher than the corresponding month of 2020, when the effects of the Covid pandemic were yet to be felt (Chart 1). Over that period, the price of maize had risen from $168.71 to $245.24 a metric tonne or by 45.4 per cent; of rice from $426.45 to $531 a metric tonne or by 24.5 per cent; and that of wheat from $238.98 to $$276.63 a metric tonne or by 15.8 per cent. The spike is not restricted to grain and soyabean but affected edible oils as well (Chart 2). The price of coconut oil had risen from $844.12 to $1438 a metric tonne over the year ended February 2021 or by 70.4 per cent. There is some unevenness, however. The increase in the case of sunflower oil over that period was only 8.1 per cent. But, overall, the Food and Agricultural Organisation’s (FAO’s) price index for cereals had risen by 26.5 per cent and that for vegetable oils by 51 per cent between February 2020 and February 2021. The cereals price index (that relates current prices to an average of 2014-16 prices set to 100) stood at 125.7 in February 2021, a level last exceeded in July 2013. In the case of edible oils, the index at 147.4 in February 2021 was at its highest since February 2012 (Chart 3).

This spike in prices is surprising, since they had fallen during the months when supply disruptions due to transportation bottlenecks were most severe. While supply chains are not back to the pre-pandemic normal, things have definitely improved in recent months. Further, there is no major shortage of physical supplies. Thus, data from the FAO show that supply (or production plus opening stocks) in the world cereal market touched 3,580 million tonnes in 2020-21, as compared with 3,541 million tonnes in 2019-20 and 3,505 million tonnes in 2018-19.

Weather conditions have affected production in some locations. Dry conditions have adversely affected soyabean production in Brazil and Argentina and corn production in Ukraine. But given good harvests in recent years, inventories of most cereals are comfortably high. Wheat inventories, for example, are placed at 292 million tonnes in 2020-21, up from 277 million tonnes in 2019-20, and 5 per cent higher than the average inventory level in the previous three years. So, besides the still persisting pandemic-induced supply chain disruption, the cause for food price inflation is not the inadequacy of the produce.

But there are other ways in which the demand-supply balance has been affected. One is stockpiling by consumers and countries, fearing that a new wave of the pandemic may disrupt supply chains again. Grain importing countries, such as China, Egypt, the Philippines, Algeria and Morocco, are rebuilding their reserves, which were depleted during the first wave of the pandemic. China, in particular, which starting May 2020 released substantial stocks of grain held in its strategic reserves to rein in rising grain prices, has resorted to large imports. As compared to normal imports of 3-5 milion tonnes of corn in a year, it placed orders for as much as 11 million tonnes in 2020. It has also resorted to imports of soyabean, which is an important ingredient in livestock feed, given the need to raise its pig herd population that was shrunk by an African swine fever outbreak. In response to these demands some grain exporters, like Russia and Vietnam, have placed restraints on exports of agricultural commodities like wheat and rice, to shore up domestic availability, especially when domestic production performance has been indifferent or poor. To top it all, transportation costs have also been rising. The International Grains Council reports that the current levels of freight tariffs for grains and oilseeds are higher than in all months since October 2019.

The impact that the surge in stockpiling and the imposition of restrictions had on actual supplies to markets, by triggering a rise in prices, has encouraged speculators such as hedge funds to play the market in search of high returns. On March 1, 2021 Saxo Bank reported that the combined net long positions held by hedge funds across 24 major commodity futures stood at a record 2.7 million lots, valued at $144.4 billion. Long positions are purchases of the underlying asset made in expectation of a price rise. Short positions reflect a commitment to sell at a set price, even when the seller does not yet hold the commodity, on the expectation that market prices would fall below the negotiated level. When, net long positions are positive, investors display proclivity to buy into commodities in expectation of a price increase. Agricultural commodities have recently been important targets in this tendency to go long, with long positions touching a new record at 1.3 million lots, led by sugar, coffee and soybeans. This speculative thrust has also been fuelled by the availability of cheap finance as a result of easy monetary policies. Central banks the world over have injected vast sums of cheap liquidity into their economies in the hope that this would spur consumption and investment. What that policy has actually triggered is a search for yields to be earned with capital that costs next to nothing. With commodity markets increasingly financialised in recent years, they have become targets of such footloose capital.

Given the loss of incomes suffered by the poor and middle classes as a result of the pandemic and the response to it, the rise in prices driven by these factors can be devastating if these trends persist. To simplify and summarise, the policy response to the pandemic is driving tendencies that can precipitate a nutritional crisis. Already, memories of past riots in different countries because of unaffordable food prices are being recalled. What was paradoxical then and is true even now is that it is not missing grain but just reduced incomes and high prices that drive the hungry to such action.

(This article was originally published in the Business Line on March 8, 2021)