The weaponization of tariffs by US President Donald Trump has clearly generated fear and loathing…

A Market gone awry C. P. Chandrasekhar and Jayati Ghosh

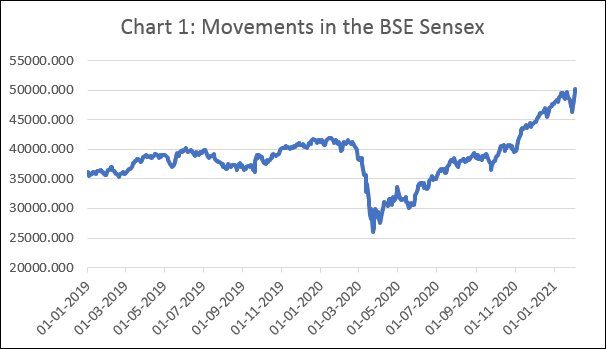

It defies all logic. As expected, once the implications of the Covid-19 contagion began to be absorbed, the BSE Sensex lost 37 per cent in value, falling from a level just above 41,000 on February 19, 2020, to just below 26,000 on 23 March 2000 (Chart 1). That was the day when the nationwide lockdown was declared and three days before the first of the government’s stimulus packages was unveiled. The lockdown triggered the severe contraction that overwhelmed the economy over the next two quarters. Yet, starting March 23, the Sensex got off its trajectory of decline, and set itself on a rising curve, which despite fluctuations seems relentless. On February 3, 2021, a little more than 10 months since the latest rise began, the index cross the 50,000 mark, registering a 93 per cent increase relative to its March 23, 2020 low.

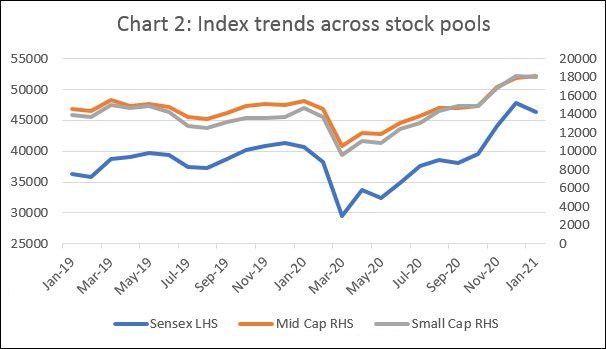

Given real economy trends this was clearly a heady, speculative boom, reflecting “irrational exuberance”. It could, of course, be argued that the Sensex includes scrips of just 30 blue-chip industrial and financial firms, investments in which may be indicative of the market’s own version of a “flight to safety” in the middle of a pandemic. However, as Chart 2 shows, the trend which the Sensex displayed over these months has characterised movements in the stock indices for mid- and small-cap firms as well. The speculative fever had affected all pools of stocks in the equity market.

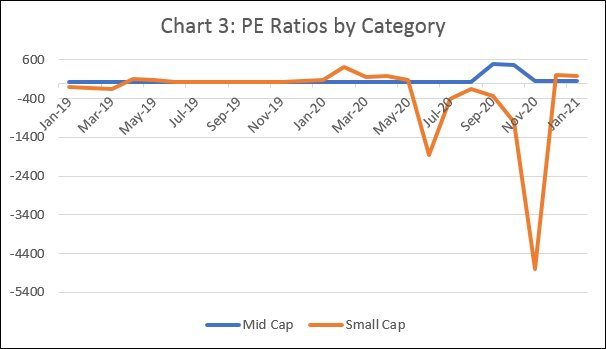

This absence of difference in the trend between the Sensex and the small and mid-cap indices is remarkable, given the sharp difference in the trend in the price to earnings (PE) ratios characterising these groups of stocks. The PE ratio for Sensex scrips as a group more or less tracked the trend in the index itself, with the ratio falling from 23.2 in February 2020 to 17.8 in March 2020 and then almost doubling to 33.5 in January 2021, before settling at 31.8 in February. Clearly the prices of stocks were running rapidly ahead of earnings, pointing to the speculative mood in the markets.

However, once we turn to movements in the PE ratios of mid- and small-cap stocks, the trend goes awry. The PE ratio for mid-cap stocks falls from 27 in February 2020 to 19.9 in March 2020, rises to 33.7 in August 2020, spikes to 500 and 460 in September and October respectively, before experiencing a fall to between 61 and 66 over November 2020 to January 2021 (Chart 3). The PE ratio for small cap stocks is characterised by an even higher degree of extreme volatility. But what is remarkable is this volatility puts the ratio in negative territory over June to November 2020, with the PE ratio fluctuating between -159 and -4798. Firms were recording losses in the previous months used to compute the earnings per share, but that did not exempt them from the speculative frenzy that has overcome investors.

These wild trends don’t seem to have scared away investors. One “calming factor” cited by observers who don’t seem too worried by the heady boom in a crisis year is that this is a global phenomenon, led by the large volume of cheap liquidity released by central banks worldwide to counter the Covid-induced recession. This is indeed a factor, as reflected in the fact that net inflows of foreign portfolio investment in equity (excluding bonds and hybrids) rose from a total of $4.7 billion during the months May 2019 to January 2020 to $24.8 billion during May 2020 to January 2021. The more-than-five-fold increase in net inflows into the market also underlies the sharp rise in stock values, which further fuels the surge in inflows.

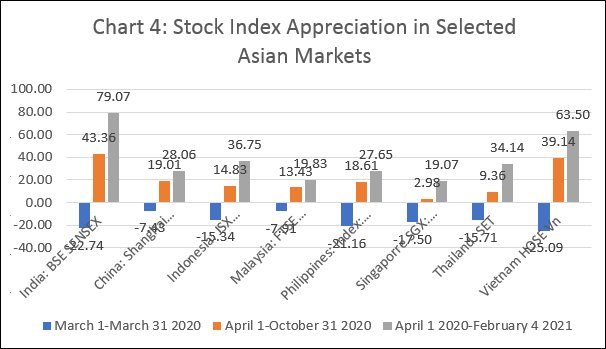

But it is noteworthy that the boom in India’s market has been larger than in most Asian emerging markets. Chart 4 shows the decline in the market indices in 8 different Asian emerging markets over March 1 and March 31, 2020, and the rise in these indices over April 1 to October 31, 2020 and April 1, 2020 to February 4, 2021. While the Sensex’s decline of 23 per cent in March 2020 was near-equalled or marginally exceeded only in the Philippines and Vietnam, its rise over the next two periods, of 43 per cent and 79 per cent respectively, was the highest among all Asian emerging markets, with only Vietnam being close in terms of magnitude. Markets in China, Indonesia, Malaysia, the Philippines, Singapore and Thailand, while displaying similar fluctuations, saw significantly lower rise in indices after March. These six markets saw indices rising by 19-37 per cent over April to January, as compared with India’s 79 per cent.

While this differentiated performance could be partly due to India being a more favoured destination for investors from abroad loaded with cheap capital, it also suggests that investors in India, consisting of corporates, financial institutions, high net worth individuals and retail investors operating directly and through mutual funds, must have joined foreign investors in riding the boom. The resulting thirst for stocks of this flock of investors possibly explains the spill-over of the boom to mid-cap firms, and small-cap firms recording negative PE ratios.

The exceptional nature of the boom in India may have an additional explanation. Starting with a major corporate tax concession granted in September 2019 (which brought the effective tax rate down from 34.6 to 25.2 per cent), the NDA government has persisted with pushing ahead with what are seen as market- and business- friendly policies through the pandemic. This included passing legislation putting in place new labour codes, liberalising the agricultural trade and facilitating contract farming. It has also made clear that the disinvestment and privatisation drive that had been stalled during fiscal 2020-21 would be accelerated in the coming year. It has declared the monetisation of existing state assets, including land, would be relied on to finance new investment. And, it has laid out an agenda to privatise public financial institutions in banking and insurance. These and other similar moves speak of a future in which new opportunities may open up for the private sector, even if only for a few leading corporates. The expectations higher profits and new riches these moves generate may also be fuelling the frenzy in India’s equity markets.

(This article was originally published in the Business Line on February 8, 2021)