Donald Trump’s tariffs have disrupted supply chains, roiled global markets, and escalated the trade war…

Wrecking Fiscal Federalism C. P Chandrasekhar and Jayati Ghosh

India’s Constitution puts the bulk of responsibility for the basic goods and services to be provided to citizens on to state governments. That is also why it mandated that independent Finance Commissions be appointed every five years to determine the distribution of tax revenues between Centre and the various states. Successive Finance Commissions (FCs) have also recognised that state governments necessarily require more resources to fulfil their obligations, which is why the share of tax revenues to be devolved to states has been steadily increasing across such Commissions, from 29.5 per cent in the 11th FC to as much as 42 per cent in the 14th FC.

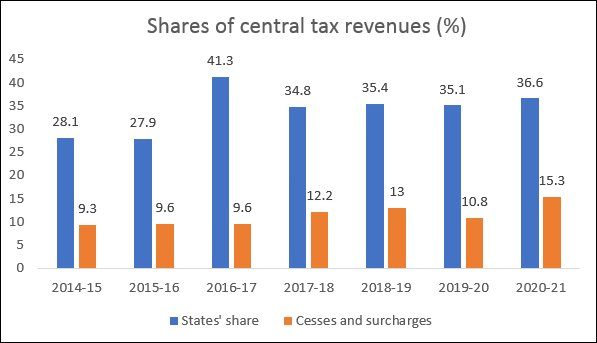

However, while grudgingly accepting the 14th FC’s award, which was announced in April 2015, the Modi government moved rather quickly to undermine it. It used the obvious available loophole in the Constitution: while tax revenues are to be shared with the states, cesses and surcharges are exempt. Using this loophole, the central government has been increasing the share of taxes collected through such cesses and surcharges, and therefore reducing the share of states in the total divisible pool. In fact, as Figure 1 shows, the share of the states never reached the mandated 42 per cent even in the peak years of 2016-17; thereafter, it has been suppressed as the central government moved to redirect its additional resource mobilisation to the cesses and surcharges that it could jealously guard as its own. By the current year, the share of these in total tax collections is estimated to be more than 15 per cent, a massive increase from the pre-Modi years.

Figure 1

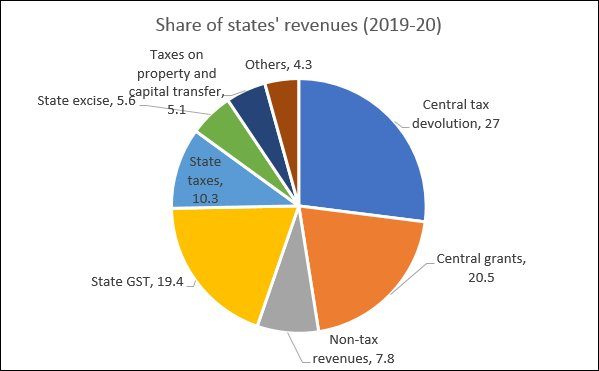

In this period a further centralising tendency occurred with the introduction of the Goods and Services Tax (GST) which effectively denied state governments any ability to raise their own revenues, other than through sales taxes on alcohol and excise duties on fuel, which are exempt from GST. As a result, states are now dependent on the Centre for nearly half of all of their resources, as shown in Figure 2. And because the GST rates are also not in their hands, they have no control over more than two-thirds of their revenues.

Figure 2

This became an even more serious matter for state governments during the pandemic, when revenues of state governments plummeted, to a greater extent than they did for the central government for many states. After invoking the centralising National Disaster Management Act to declare a national lockdown without consulting or informing states, the Centre then proceeded to avoid any fiscal or other obligation to deal with the pandemic or the consequences of its own actions. The Centre left it largely to the state governments to deal with the additional health and security measures required, as well as the need to compensate for the economic distress, and somehow assist the recovery of livelihoods in whatever ways they could.

This is when the dues they were already owed by the Centre, in the form of the agreed and legislated GST compensation, would have been absolutely critical in plugging the gaps. (As a reminder, when the GST was introduced, the Centre had committed to compensating states to ensure that the tax revenues accruing to them would increase by 14 per cent every year for 5 years, to be paid out of a fund created by bringing in a GST compensation cess.) But the Centre has been tardy about paying this, delaying the promised bi-monthly payments. Even when the lockdown started, the states had not been paid the compensation due for the period December 2019 to March 2020. Once the lockdown led to collapsing economic activity and declining tax revenues, the Centre denied the states their full legal dues of the GST compensation cess, claiming that it had not received sufficient funds through the cess.

This was disingenuous at the least. The Comptroller and Auditor General of India (CAG) had already found that the Union government in the very first two years of the GST implementation wrongly retained Rs 47,272 crore of GST compensation cess that was meant to be used specifically to compensate states for loss of revenue, and directed it to other purposes!

Because of the backlog and the further decline in tax collection, the estimated shortfall in GST compensation for 2020-21 is Rs 2.35 lakh crore (with only Rs 65,000 crore likely to be collected against the projected Rs 3 lakh crore). But the Centre simply refused to meet its legal obligation, which it could easily have done by borrowing and repaying the amount through future cess collections.

Instead, after some back and forth, the Finance Minister proposed a complicated arrangement whereby the states would borrow a smaller amount (Rs 1.1 lakh crore) from the Centre. It would involve a back-to-back arrangement whereby the Centre (which can borrow at lower rates than the states) would lend directly to the states. All this only to avoid this amount being shown in the books as expenditure by the Centre, so as to avoid a larger fiscal deficit in the budgetary accounts.

Consider the farcical nature of the plan: the Centre owes the states money; but instead of paying up, it lends the states some part of what they are owed from the Centre. Even this is being seen as a concession, because earlier the Finance Minister had offered only to allow the states to borrow the amount from the market. This is possible only because of the extremely unequal power relations between Centre and states. While some states are still holding out for their rightful dues, most have fallen in line, out of sheer desperation because of the need to pay salaries and keep their government seven minimally functional.

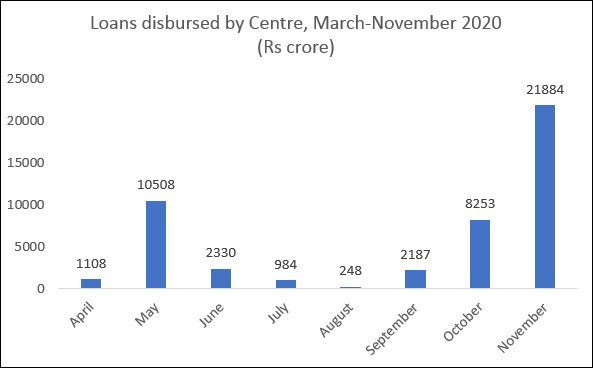

As Figure 3 indicates, this process, which began in late October, led to significant increases in loans disbursed by the Centre (which are almost entirely to the state governments). Even so, the amounts provided fall well below the states’ needs, especially given the continuing economic slowdown and loss of livelihood.

Figure 3

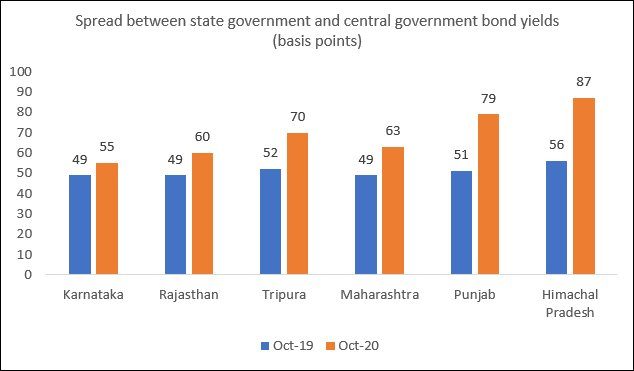

Figure 4

The power imbalance between Centre and states comes not only from the fact that the Centre can control borrowing by the states under the Constitution; it is also due to the fact that in financial markets, the states typically face worse conditions and their debt is more expensive. Furthermore, the pandemic has worsened the conditions they face in bond markets. Figure 4 provides data for just a few states, which indicates the extent to which the spread between the yields on bonds they issue and the central government’s bonds have increased over the past year.

In this situation, given the unashamedly intransigent attitude of the Centre, most states have seen no option but to comply. But this is not a sustainable situation. And it has completely eroded any trust between Centre and states, which is essential for functioning federalism. Far from the “co-operative federalism” that was promised, it appears that this coercive fiscal pressure may undermine the basis of any federalism at all.

(This article was originally published in the Business Line on January 25, 2021)