The weaponization of tariffs by US President Donald Trump has clearly generated fear and loathing…

India’s External Sector during the Pandemic C. P. Chandrasekhar and Jayati Ghosh

The complete absence of any meaningful fiscal response from the Indian government in the face of one of the biggest economic crises ever faced, cries out for explanation. One argument has been that the central government is concerned about its external vulnerability: a large increase in public spending could generate higher imports, thereby worsening the trade deficit at a time when volatile capital flows have already made the balance of payments vulnerable.

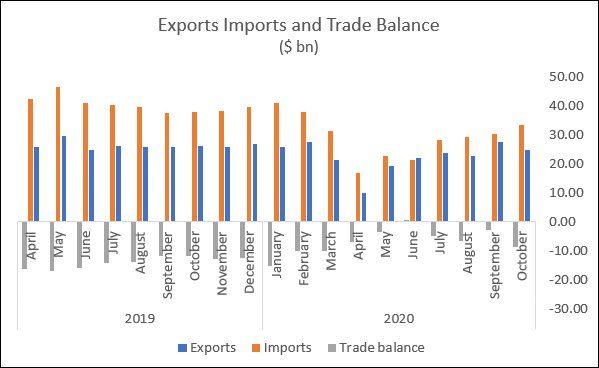

Is this fear justified? It is certainly true that India’s external sector has been weak and vulnerable for some time now, and a dramatic exodus of foreign capital from all emerging markets including India in April 2020 was yet another indication of the fickle behaviour of international capital markets. Figure 1 shows that the weakness on the trade front continues, with exports, which slumped in March and April, recovering thereafter but still in October 2020 remaining below the levels of the previous year. However, imports also slumped, largely reflecting the contraction of the domestic economy and the collapse of demand, along with declining world prices for some major imports like oil. As a result, the trade deficit shrunk substantially in the period April to September, with a minor increase in October 2020 as imports grew again while exports fell.

Figure 1: The trade deficit has shrunk because imports fell more than exports

Source for all data: https://dbie.rbi.org.in/DBIE/dbie.rbi?site=publications

The decline in the trade deficit helped the current account to move from deficit to minor surplus in the January-March 2020 quarter, and this current account surplus actually grew in April-June 2020 to nearly $20 billion. This was also because remittances from overseas migrant workers and exports of software services remained high enough to balance other outflows of profits and dividends and outward remittances of resident Indians.

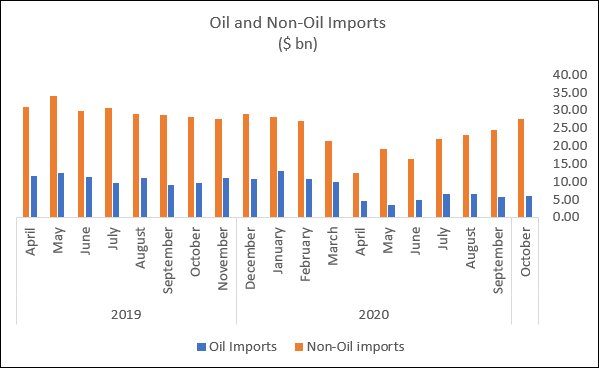

Figure 2: Non-oil imports have recovered faster than oil imports

Within total imports, oil imports recorded the most significant declines, as evident from Figure 2. Some of this was obviously related to the curbs on travel, transport and production during the lockdown, and the domestic slump in economic activity following upon that lockdown. But it was also related to the collapse of global oil prices: crude oil prices fell to less than $10 per barrel in April 2020, and even in December 2020 oil prices were nearly 40 per cent lower than a year earlier. The recovery of non-oil imports only partly reflects the increase in production after the “unlocking”, since some of the imports could also be replacing domestic production especially from micro and small enterprises that were destroyed by the lockdown.

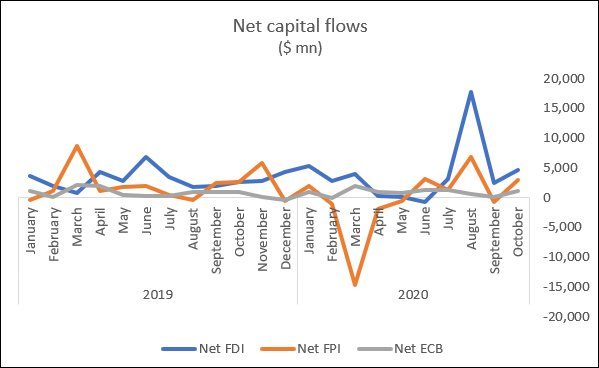

As in other emerging markets, cross-border capital flows were very volatile over this period (Figure 3). There was massive outflow of foreign portfolio capital in March and April, and subsequently a minor recovery as the massive infusions of liquidity in the advanced economies created yet another surge of footloose capital looking to benefit from easy access to cheap finance by investing in developing countries with higher interest rates. This peaked in August 2020, but the inherently unstable character of such flows was evident by September, when there was once again a net outflow.

There was also a large surge in foreign direct investment in the month of August 2020. The main recipient was Jio Platforms, the telecom subsidiary of Reliance Industries, in which Google alone invested $4.5 billion, while an earlier $5.7 billion deal Jio had made with Facebook also probably also fructified around this time. Jio also received other investments, including from private equity. Reliance also sold around 10 per cent stake in its retail sales unit to foreign investors for around $6.7 billion. These foreign investment inflows are effectively part of a broader tendency towards vertical and horizontal concentration in the Indian corporate sector, in which organised industry and services are increasingly coming under the control of a few key oligopolistic players with strong links to the ruling governments at centre and state levels.

Figure 3: There were big capital inflows in August 2020

Another constraint to enhanced public spending is often presented in terms of the public debt and fears of it increasing to unsustainable levels. In developing countries, that is most often expressed in the concerns about external public debt. But in India, such fears are completely misplaced. At the end of March 2020, India’s external debt amounted to less than $60 billion, of which $48 billion was government borrowing (46 per cent of which was taken on concessional terms with lower rates of interest). This amounted to only 20 per cent of GDP, well below any levels that could be seen as a cause of concern. So the external constraint cannot be responsible for the reticence in central government spending now. (Total public debt to GDP is currently higher, at nearly 90 per cent of GDP, but since that is dominantly denominated in rupee terms and owed to Indian residents, repayment is not an issue for a government that still has the power, through the central bank, of issuing its own currency.)

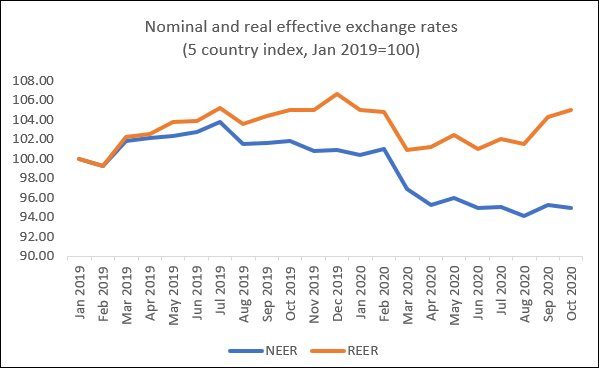

Figure 4: The rupee continued to depreciate

It is interesting that despite the shift from current account deficit to surplus and the revival capital inflows after the slump in March and April, the rupee has continued to depreciate in nominal terms, making it the worst performing currency in Asia over 2020. Figure 4 shows the trade-weighted effective exchange rate indices (vis-à-vis the five main trading partners). While the nominal exchange rate began declining in mid-2109, the decline was especially sharp from March 2020 onwards, and the nominal value of the rupee has stayed low thereafter. Meanwhile the real effective exchange rate has started to rise again, largely because rates of Inflation in India have been higher than in the trading partners. This is essentially cost-push inflation, driven not only by supply bottlenecks that emerged because of the unplanned lockdown, but also by the central government’s aggressive increases in excise duties and taxes on fuel, which have been increased by nearly 350 per cent during this government’s tenure. These increases in central government excise duties continued during the pandemic, even as ordinary Indians were struck by major livelihood losses.

In sum, the external sector is clearly not a source of hope at present; but neither does it create any constraint on significantly increased expenditure by the central government.

(This article was originally published in the Business Line on December 28, 2020)