The weaponization of tariffs by US President Donald Trump has clearly generated fear and loathing…

A Misleading Signal from the Trade Front C. P. Chandrasekhar and Jayati Ghosh

Provisional trade figures released by the Ministry of Commerce indicate that India’s aggregate trade balance over the period April-August 2020 was in surplus to the tune of $14.2 billion, as compared with a deficit of $45.11 billion in the corresponding months of 2019. In normal times this emergence of a surplus trade balance for a country that is chronically deficit would be a welcome development. But these are not normal times. Global growth has slowed since 2019, which would have adversely affected India’s exports. Oil prices have been volatile, but have broadly swung in India’s favour reducing the country’s oil import bill and improving its trade balance. And the Covid-19 pandemic has triggered a crisis globally and in India, which would have resulted in both a drop in exports as also in import compression, because of the severe contraction in domestic GDP during the first and (possibly) second quarters of financial year 2020-21. A careful assessment of what the trade data reveal is, therefore, in order.

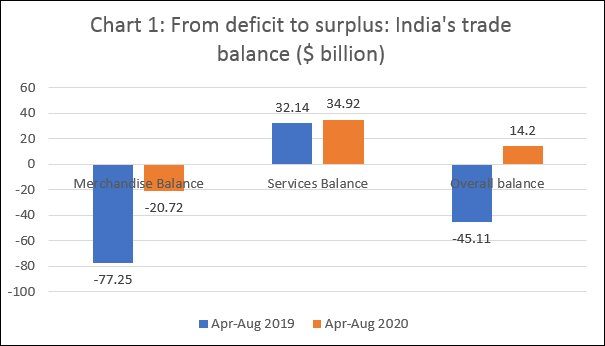

As is to be expected, the changed circumstances have affected merchandise trade to a greater extent than the trade in services. Merchandise exports over April-August 2020 fell by 26.65 per cent relative to the corresponding months of 2019. But the fall in imports was, at minus 43.73 per cent, much sharper on a larger base. As a result, the merchandise trade deficit was less than one-third of its earlier level, falling from $77.25 billion to $20.72 billion between April to August 2019 and 2020 respectively (Chart 1). In the case of the services trade, the April to August balance is estimated to have improved from $32.14 billion in 2019-20 to $34.92 billion. (The services trade figures for August are Commerce Ministry estimates, since the Reserve Bank of India is yet to release figures for that month.) This combination of a fall in the merchandise trade deficit and improvement in the services trade balance has resulted in a transformation of an overall trade deficit of $45.11 billion during April to August 2019 to a surplus of $14.2 billion during April to August 2020.

The sharp decline in the merchandise trade balance between the two periods was undoubtedly influenced by the fall in world oil prices. For example, the price of the benchmark Brent Crude variety of petroleum ruled at $69 a barrel in April 2019 as compared with $20 a barrel between in April 2020 and at $63 a barrel compared with $44 a barrel in August 2019 and August 2020. These lower prices, combined with the fall in consumption of petroleum products because of the severe lockdown imposed by the government starting late March 2020, should have reduced India’s oil import bill and oil trade deficit significantly. It is true that India has in recent years been a significant exporter of petroleum products, so that the global recession and the fall in global oil prices would have impacted exports as well. But if we take the period April to July 2020, oil exports from India fell by $8.16 billion, whereas oil imports into India fell by $25.32 billion. Thus, the oil price bonanza did play a role. But so did the severe recession in India that curtailed oil imports.

The contribution of the recession was all the greater because it affected a range of imports. If we consider non-oil and non-gold imports, the value of this group of imported products that stood at $139.75 billion in April-August 2019-20 fell to 86.17 $billion in April-August 2020-21. On the other hand, non-petroleum and non-gems and jewellery exports fell only to $83.24 billion during April-August 2020-21 from $99.65 billion during the corresponding months of the previous year. Thus, the fall in the imports of core non-oil products driven by domestic recession was steeper than the fall in core exports resulting from the recession in India’s principal trading partners.

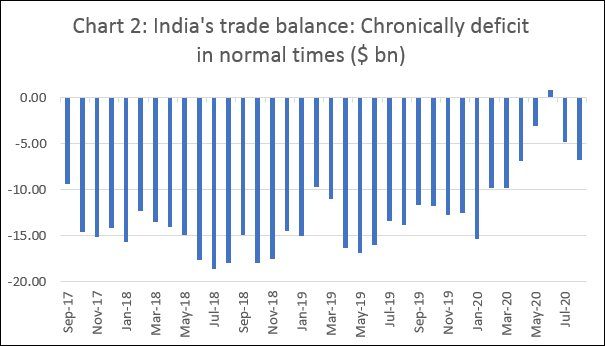

The effect on the merchandise trade balance of this post-Covid recession-induced fall in India’s imports was significant. India’s monthly trade deficit, which was either near or substantially above $10 billion from September 2017 to March 2020, fell significantly in all months after March and even turned surplus in June 2020 (Chart 2).

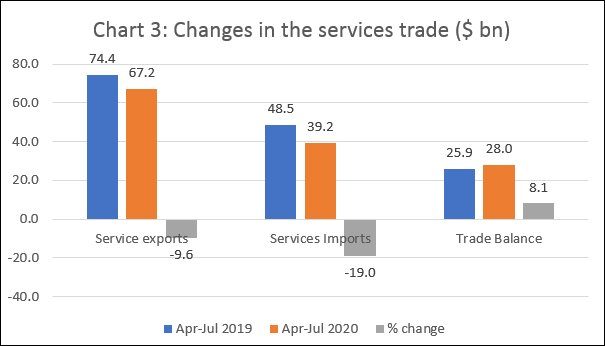

The importance of the domestic recession in explaining trade trends is revealed more clearly by the evidence on trade in services, which is not clouded by the effects of the global fall in oil prices. If we consider the period April to July, India’s services exports totalled $74.4 billion in 2019 and $67.2 billion in 2020, reflecting a fall of 9.6 per cent (Chart 3). As compared to this, affected by the domestic recession, services imports fell from $48.5 billion to $39.2 billon over the respective four-month periods, or by a much higher 19 per cent. This helped raise the positive balance in the trade in services by 8.1 per cent, which contributed to the observed “improvement” in India’s overall balance of trade. In the case of services, clearly the much sharper recession at home brought down imports while exports were affected less by the global crisis.

In sum, while the fall in global oil prices did contribute to the reduction in India’s import bill, a major factor explaining that reduction is the much sharper fall in non-oil imports of both goods and services as compared with the fall in exports of non-oil goods and services. The recession also meant that factors operating before and after the Covid-19 shock prevented India from reaping the benefits of low international oil prices, which in normal circumstances would, by capping inflation and increasing the government’s manoeuvrability, helped trigger an acceleration in growth. Seen in that light, the transformation of India’s balance of trade from deficit to surplus, even if not temporary, is not a sign of improving economic health. It shows that the way the Covid-19 shock was handled by the Indian government has had more deleterious effects on its economy, than is being experienced by its trading partners.

(This article was originally published in the Business Line on September 21, 2020)