Donald Trump’s top economic advisor claims the President has weaponised tariffs to ‘persuade’ other nations…

Central Government Fiscal Stance during the Pandemic C. P Chandrasekhar and Jayati Ghosh

As India faces the biggest economic crisis since Independence, it is being led by a central government in denial about the severity of the impact on lives and livelihoods, and spreading false hopes about the immediate future. The Monthly Economic Report of the Union Finance Ministry claims that already the economy “is witnessing a sharp V-shaped recovery” suggesting that nothing drastic needs to be done by the government to return to a stable and positive economic growth trajectory. This may just be yet an exercise in perception management that the current government excels in, but it presents a misleading picture of the state of the economy. Even more worrying, it could lull the government into believing its own rhetoric, and thereby not taking the measures necessary to ensure economic revival.

One indication of this is in the fiscal stance taken during the period of the lockdown and its immediate aftermath, during the so-called “Unlock” phases. Remember that the Indian government imposed one of the most stringent lockdowns in the world, that too with only four hours’ notice, on to a population that is dominantly without any form of social protection. It then did not provide compensation for the livelihoods lost, even as the public health measures taken were so inadequate that the disease has continued to spread.

In the past week, India has had the highest number of daily new cases of Covid-19 in the world; it has now surpassed Brail to reach second rank in total cases, after the United States, and will soon reach number one rank as its numbers keep climbing faster than in the US. This will necessarily affect prospects of economic recovery as well.

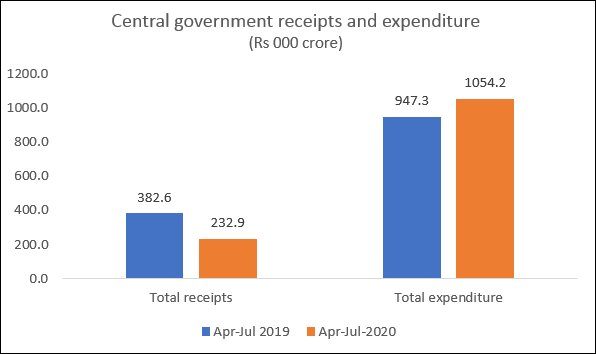

In this context, it was incumbent upon the central government to increase sharply its total spending, not only to provide relief and compensation to those deprived of incomes, but also to ensure that the economy does not collapse completely because of the poorly planned lockdown. Unfortunately, as Figure 1 indicates, the fiscal response during this period has been far short of what is required. Some will argue that this is because the government revenues were also falling and therefore it did not have the resources to spend more. But this is a completely wrong way of understanding the government’s role in the economy.

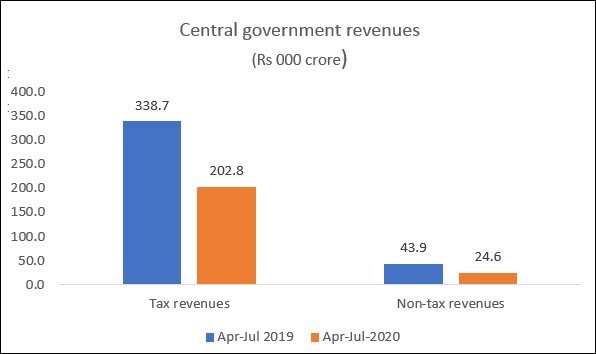

Obviously, tax receipts fell sharply (Figure 2), especially indirect taxes, which is only to be expected in a period when economic activity is forcibly curtailed. But the idea that government spending is dependent upon current receipts is mistaken, confusing the state with a household as economic agents. Unlike individuals or families, the central government by virtue of controlling the central bank as issuer of currency, can always access the resources required for its spending. The macroeconomic constraints are the fear of possible inflation or balance of payments deficits as a result; the political economy constraints stem from fear of financial markets, which tend to punish those running large fiscal deficits.

Figure 1: Total government expenditure increased only marginally year-on-year

Figure 2: Tax revenues have fallen very sharply

In the short run, and especially during the extraordinary circumstance created by the pandemic, none of these really matter. That is why governments across the world have embarked on massive spending programmes, in addition to further loosening monetary policy. Yet the Indian government, whose policies have already resulted in the worst economic performance among major countries, has been remarkably reticent about spending more to counter these forces of decline. In the four months since the lockdown was imposed in late March, its spending has gone up by only 11 per cent compared to the same period in the previous year, or less than 9 per cent in real terms. This makes barely a dent in the overall economic collapse.

This is extremely counterproductive, not only because it adds to the material suffering of the people. It also worsens the tendency for the economy to contract. As households and businesses spend less, the government needs to provide the demand (and reduce infrastructure constraints) by spending more. If it does not, then its own tax revenues will fall further as economic activity falls, and cutting its spending could paradoxically leave it with a larger fiscal deficit!

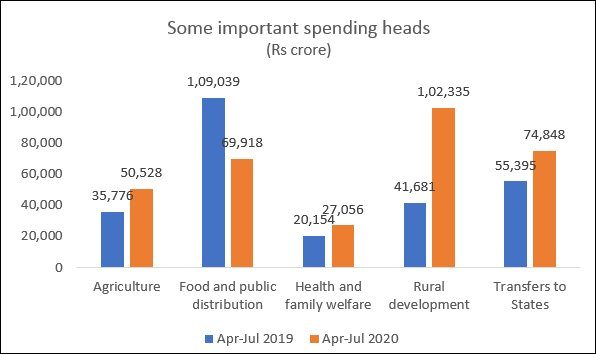

Figure 3: Spending on food and public distribution has actually fallen

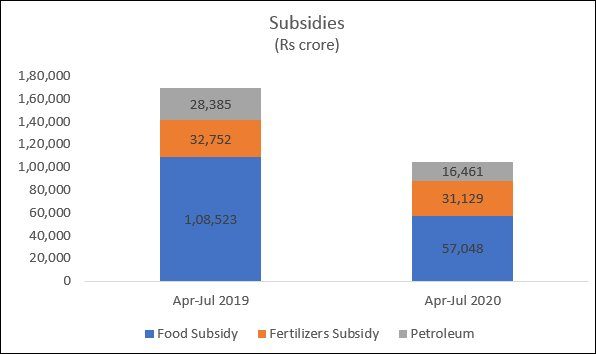

Figure 4: Both food and oil subsidies have shrunk massively

Consider some of the main areas on which significantly increased government spending could have been expected during this period. The only one that suggests some of the required increase is rural development, largely because of the much-needed higher expenditure on MNREGA. However, this urgently needs more replenishment, as many states have already reached the limit of 100 days of work for most households, and delayed transfers are causing unpaid wages to rise once again. This programme needs renewed impetus by doubling the permissible days of work to 200 and making them available to all adults, not just per household.

Transfers to states shows some increase, but this is mainly because in July the Centre finally paid the pending GST compensation dues from the previous financial year to the states. Meanwhile, state governments have been doing all the work of dealing with the pandemic and the economic fallout; the Centre’s role has been negligible. This is clearly evident from the small increase of only Rs 7,000 crore on health spending even during the pandemic. States, unlike the Centre, face a hard budget constraint—and they are rapidly running out of funds even to pay salaries.

The real shock is the decline in spending on food and public distribution. Obviously, the central government has simply not paid the FCI much of its dues in this period. FCI was already sitting on a mountain of debt because, instead of compensating it for the cost of procurement and carrying the grain, government has been making it borrow funds. This additional burden on FCI could be the death knell for FCI and, with it, the entire system of foodgrain procurement and public distribution. It is also likely that the subsidy released to the States doing decentralised procurement has been cut drastically which would put a further burden on state finances, and force them to cut down on procurement and PDS in the coming seasons. Meanwhile, the stocks held by the FCI increased from 87 million tonnes (at end March) to 104 million tonnes (at end June), with ever higher holding costs. This, when hunger is widespread and growing across the country, is inexcusable.

Meanwhile, the oil subsidy has fallen because the government has grabbed all the benefits of falling global oil prices by increasing duties. So even to the extent that the government is mobilising revenues, it is at the expense of ordinary people hurt by the crisis

This reflects both economic mismanagement and a cynical indifference to the suffering of the people at large. Public pressure will be necessary to force a shift.

(This article was originally published in the Business Line on September 8, 2020)