Donald Trump’s top economic advisor claims the President has weaponised tariffs to ‘persuade’ other nations…

Can India stay with GST? C. P. Chandrasekhar and Jayati Ghosh

July 2020 marks the completion of three years since the launch of the Good and Services Tax regime. That is long enough to allow us to take stock of how well the new tax regime is performing. If the regime is still beset with “teething troubles” the conclusion must be that there are structural flaws in its character and design that make effective implementation near impossible. If such flaws are not undermining its effectiveness, the regime should show signs of delivering the results it was explicitly or implicitly expected to yield.

An annual statistical report recently released by the Goods and Services Tax Network provides a view of the performance of the regime since its inception in July 2017 till the end of financial year 2019-20. That more or less leaves out the period when the post-Covid lockdown affected revenues extremely adversely, so the numbers are not distorted by that noise. The evidence is disappointing to say the least, though there are some positive trends.

One positive sign is that the number of taxpayers registered under GST stood at 1.08 crore as early as April 2018, and that number rose to 1.23 crore by June 2019, where it has more or less stayed since. The second is that there has been a consistent and steep rise in the cumulative number of returns filed to over 47 crores in June 2020. Finally, in the period up to March 2020, while public and private limited companies and public sector undertakings accounted for 6.5 per cent of taxpayers and 72 per cent of total collections, proprietorships and partnerships accounted for 91 per cent of tax payers and 21 per cent of collections. The presence of “informal” units among taxpayers is quite significant, suggesting that coverage is reasonably good.

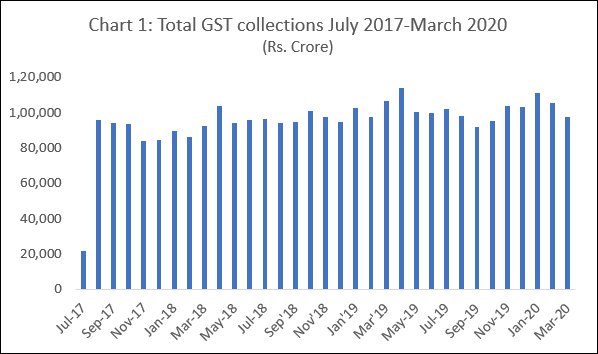

One big problem with the GST regime is the value of total collections. As Figure 1 shows, total monthly collections from state (SGST), central (CGST), and integrated (IGST) goods and services taxes and the compensation cess, first crossed Rs. 1 lakh crore in April 2018. Yet there have been only 9 out of the 33 months till March 2020 in which that mark has been exceeded in nominal terms. Further there have been only 4 months in which the figure has topped Rs. 1.05 crore. In sum, the picture is one of stagnation in GST revenue growth.

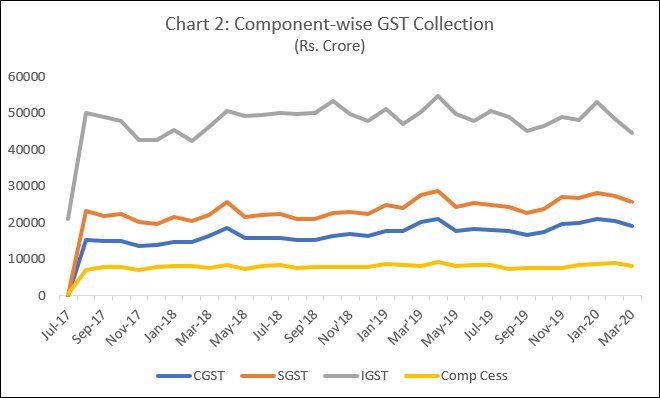

As Figure 2 shows, this sluggishness in revenue growth is true of all components of GST collections, with the peak value achieved being recorded in April 2019. In sum, even the pre-Covid deceleration of growth recorded in 2019-20 was enough to keep collections below the Rs. 1 lakh crore mark in subsequent months. The pro-cyclicality of GST collections, starting even from relatively disappointing levels, is marked. Needless to say, once the lockdown in response to the pandemic was announced, revenues collapsed.

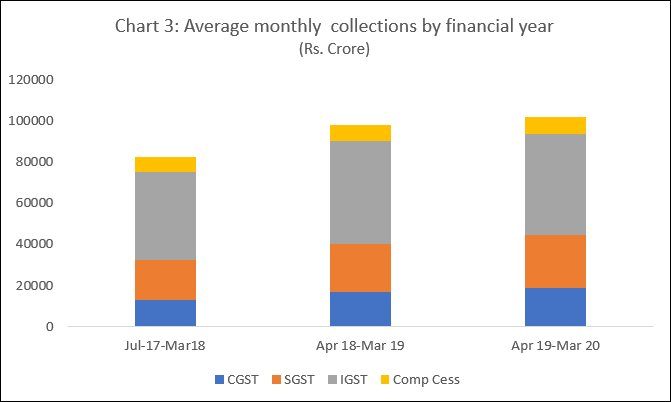

The net result is that average monthly collections in each of the three financial years (Figure 3) when the GST regime has been operative, having risen sharply from Rs. 82,294 crore in the nine months of 2017-18 starting July, to Rs. 98,114 crore in 2018-19, rose only marginally to Rs. 1,01,843 crore in 2019-20. So average monthly collections, which were 19.2 per cent higher in 2018-19 relative to the previous year, grew in nominal value by just 3.8 per cent in 2019-20. GST collections rose from 5.8 per cent of GDP in July 2017-18 to 6.2 per cent in 2018-29 and then fell to 6 per cent in 2019-20, even though GDP growth slowed in the last of these years.

If we can treat 2019-20 as a year when the “teething problems” associated with the new regime must have been largely overcome, there is no question that this performance is poor. And given the shift that has occurred over time to an extremely lenient direct tax regime (especially in the case of corporate taxes), this poor performance of GST has pushed both the central and the state governments into a fiscal crisis. A remarkable feature of the transition to the GST regime was that, while the negotiations that preceded its launch were complex and protracted, the new regime was consistently presented as one that would only be growth and development positive—a “game-changer”. If nonetheless there were immense difficulties in putting it in place, it was argued, it was only because of the messy nature of India’s quasi-federal polity and the unwillingness of the states to cede taxation powers, even if that would ensure uniformity in taxes across the country and absence of cascading effects with taxes being levied even on prior taxes paid. In addition, there were many problems to be resolved, such as the number of tax rates or slabs to institute (since not all commodities varying from essential to sin goods could be taxed at the same rate), what these rates should be, what would be a weighted average rate that would be “revenue neutral” so as to ensure that the growth of national GST collections would at least correspond to expected revenue growth from taxes the GST would substitute, and so on.

It was clear even then there were many uncertainties. Moreover, it was accepted that initially, revenue growth of some (if not all) states would fall short of what they would get under the old regime. This necessitated a promise of compensation if revenue growth fell short of 14 per cent a year for five years, with a special cess provided to finance that compensation. Clearly, the idea was that in those five years the rates would be tweaked to ensure a minimum 14 per cent growth in GST collections for each state.

With hindsight it is clear that the problems that a GST-type regime would encounter in the Indian context were underestimated. Even questions as to how many rates should be instituted and what they should be, and which commodities should be placed under each of those rates had to be repeatedly revisited. But despite such tweaking, revenue growth has been unacceptably sluggish. And as the post-Covid experience has starkly brought out, states will possibly be hit hard after the period when they are to be compensated for revenue growth shortfall ends two years from now.

One solution that would be discussed would be to raise tax rates in all slabs, although the impact on demand and revenue is unclear. There is also the question of whether the resulting tax structure would be socially acceptable. Unable to resolve the problem together, states may well demand that they be allowed to return to a situation where the taxation powers they ceded to the GST Council and the Centre are restored to them. The GST could still turn out to be a failed experiment.

(This article was originally published in the Business Line on July 27, 2020)