Donald Trump’s top economic advisor claims the President has weaponised tariffs to ‘persuade’ other nations…

Footloose Capital and the Covid Shock C. P. Chandrasekhar and Jayati Ghosh

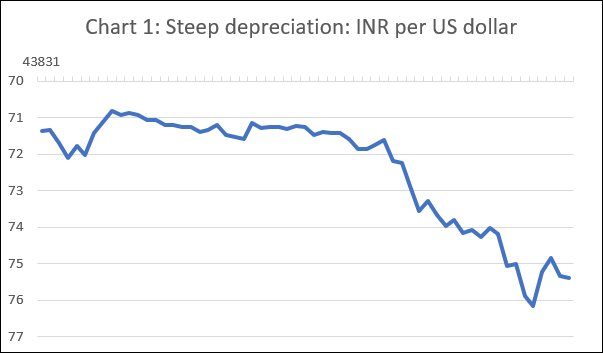

One of the many symptoms of the economic shock resulting from the Covid-19 pandemic is a sharp depreciation of the Indian rupee vis-à-vis the dollar. The value of the rupee fell from 71.3 to the dollar on February 12 to 76.2 to the dollar on March 24, or by close to 7 per cent in a month and a half, with much of the fall occurring over the month ending March 24 (Chart 1). There is little disagreement that this downward drift was the result of the exit of portfolio capital from India, since depressed domestic demand and falling international prices for commodities such as oil should have reduced demand for foreign currency and held up the currency.

India’s predicament reflects a tendency seen across emerging markets, but there are India-specific features that are troubling. By March this year, when the Coronavirus pandemic had overwhelmed Europe, UK and the United States, the effect on financial markets was visible. Not only were stock indices collapsing across the world, but there were signs of a flight of capital out of emerging markets. In periods of uncertainty financial investors pull out of investments, either to cut losses or book profits to cover losses elsewhere. And, with globalisation, those decisions are felt with force across the globe, including in the developing countries. Estimates from the Institute of International Finance cited by the Financial Times place the volume of capital withdrawn from emerging market financial assets since January 21 at $95 billion, which is four times as much as the capital fight experienced over a similar period after the onset of the 2008 crisis.

This capital reversal follows a period of large inflows driven by easy liquidity conditions and facilitated by liberalisation of capital controls. Across emerging markets, with some salient exceptions in specific periods resulting from idiosyncratic causes, the last few years have seen a surge in capital inflows. Unconventional monetary policies, involving “quantitative easing” and low interest rates, provide access to cheap capital which investors diverted to lucrative emerging markets. Being short term and footloose in nature, these flows can be reversed rather quickly in periods of uncertainty.

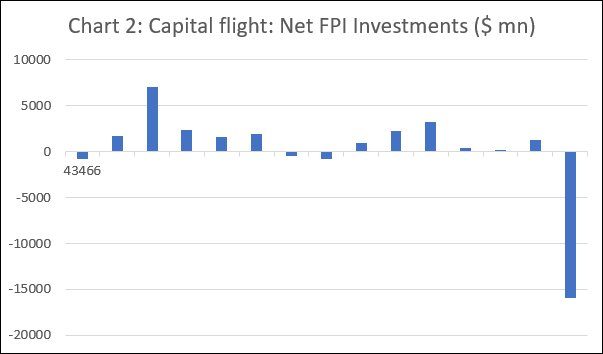

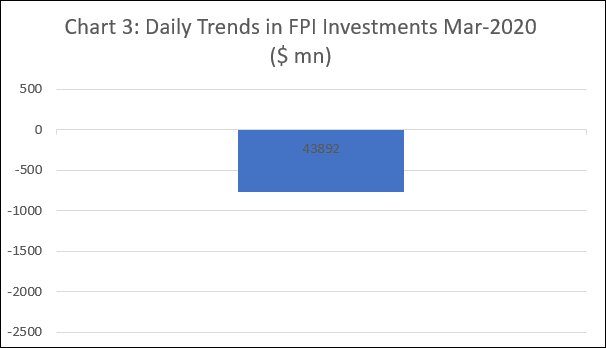

India has been a victim of such a sudden turnaround with heightening uncertainty about the intensity of the Covid-19 induced economic shock. Net foreign portfolio investments in India’s equity and debt markets, which were positive in all but three months since January 2019, turned sharply negative in March. Net outflows of investments in that month alone amounted to $15.9 billion, which exceeded total net inflows of $12.9 billion over the preceding year (Chart 2). The tendency seems to be relentless, with outflows being negative on all days excepting one in the month of March (Chart 3).

It could be argued that this negative trend would be partly neutralised by the fall in oil prices, that would help India’s balance of payments and reduced the demand for dollars. But, for India, a steep fall in oil prices has conflicting effects. While it reduces foreign exchange outflows on account of imports, it also adversely affects remittances that are a major source of support for India’s balance of payments. India, with around 18 million migrants estimated to be living abroad, is the world’s largest recipient of remittances, estimated at $78.6 billion in 2018. The Indian diaspora is located primarily in the UAE (3.4m people), US (2.7m) and Saudi Arabia (2.4m). Preliminary figures suggest that slowing global growth and falling oil prices had begun to adversely affect remittance inflows by the last quarter of 2019, with inflows falling from $16.4 billion to $15.2 billion between the third and fourth quarters. With oil prices having collapsed with the Covid-19 crisis and unemployment soaring in the US in the wake of the sudden stop in economic activity, remittance flows are likely to fall sharply.

In sum, these are testing times for the Indian rupee, which would in all likelihood depreciate further and quite sharply in the coming months. The difficulty is that this tendency would have reverberations elsewhere in the financial system and impact the real economy as well, making a bad situation worse. One route through which the damaging effects of rupee depreciation could work their way is a spike in the rupee value of interest and amortisation payments on foreign borrowing by the Indian private sector. During the last few years when money was abundant and cheap in international financial markets, global interest rates were significantly lower than rates in India. This encouraged India corporates, often seeking to expand rapidly by relying on borrowed funds, to access loans from abroad.

More recently, two factors have fuelled this tendency. One is the increasing reluctance of banks and financial institutions, already burdened with large volumes of non-performing assets that had to be provided for, to enhance their loan books. That reticence only increased with the collapse of non-bank financial companies like IL&FS and DHFL. Unable to access adequate credit domestically when the economy was slowing, Indian businesses turned to international markets.

Interestingly, the RBI has supported this move by Indian business by relaxing rules relating to external commercial borrowing. The set of eligible borrowers and lenders was widened in early 2019; borrowers with large exposure to bank credit were encouraged to turn to non-bank debt markets, both domestic and foreign; and the central bank substantially eased rules regarding end-use of funds accessed through external commercial borrowing. In mid-2019, such funds were permitted to be used for working capital and other general purposes, and for repayment of rupee loans, including those that were stressed or had been classified as non-performing.

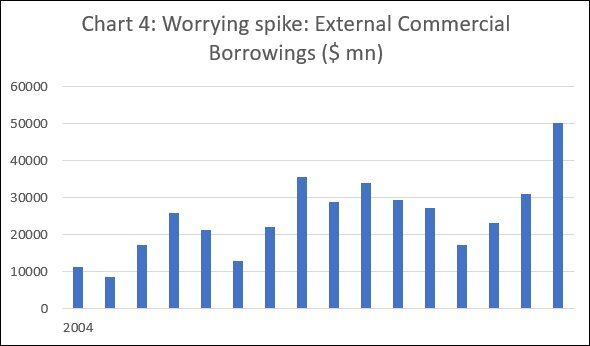

The effects of these policy measures were as expected. The annual volume of external commercial borrowing almost tripled since 2016, rising from $17.1 billion, to $23.1 billion in 2017, $31.1 billion in 2018 and $50.1 billion in 2019 (Chart 4). Repeated warnings from the regulator and industry sources suggest that significant proportions of these loans were either not hedged against currency fluctuations or were inadequately protected against them. This makes the recent rupee depreciation especially damaging. Entities exposed to a large volume of foreign currency debt would see their debt service commitments valued in rupees spike sharply, at a time when the Covid-19 shock and the stringent lockdown are triggering a domestic economic crisis. That could lead to defaults and spell bankruptcy for many. In recent times, India has seen some of its biggest business groups and richest businessmen go bankrupt. That number may rise significantly over the near future.

(This article was originally published in the Business Line on April 7, 2020)