Donald Trump’s top economic advisor claims the President has weaponised tariffs to ‘persuade’ other nations…

What Latin American can expect from US Foreign Policy In 2020 Armando Negrete

The world economy is marked by the imprint of US foreign policy. Over the last three months of the year, the United States has reactivated its political and economic interventionism in Latin America; blocked the operation of the World Trade Organization; and violated the agreements of the United Nations Security Council by attacking an Iranian military officer in a third country, under conditions of peace. The U.S. government has implemented these actions, to strengthen D.J. Trump’s presidential re-election campaign, and to help reactivate its economy, which remains in a state of productive stagnation and structural crisis.

The consequences of the US support to the coup d’état in Bolivia to the government of Evo Morales in October 2019, and the growing military threat to Cuba and Venezuela, not only express the persistence of US interventionism in the region but also the US energy prospects and the South American industrial transformations. Their complicity in the Bolivian coup was preceded by the signature of a Chinese-Bolivian joint venture for the production of lithium batteries eight weeks before the coup; Ivanka Trump’s visit to the Argentine lithium mining area in the Province of Jujuy was accompanied by the signing of two agreements for lithium production in Argentina by American firms, and the improvement of road infrastructure between that region and the port of Buenos Aires.

Together, the regional conflict constitutes the relocation of the battle between China and the US for the transformation of the oil energy matrix towards renewable energies, especially through solar energy as shown by the growing participation of Chinese foreign direct investment in Latin America, oriented towards these branches (see: http://www.obela.org/analisis/el-cambio-de-matriz-energetica-china); and America’s immense lag (and great resistance against) in clean energies.

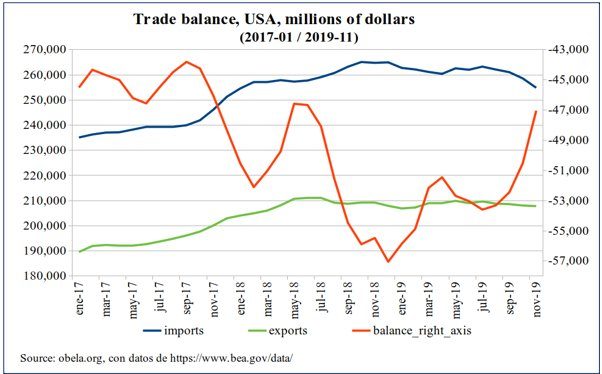

The structural decline in US manufacturing productivity (see http://www.obela.org/analisis/las-exequias-del-tlcan) and the quest to solve it are the foundation of the current US protectionism. The U.S. production structure has been tertiarized to the point that, currently, the service sector employs 78.9% of the workforce, followed by the industrial sector with 19.8%, and agriculture with 1.4%. This is a component in its loss of competitiveness in industrial products, and a reason why the trade war against China has served it little. The United States’ celebration of the reduction of its trade deficit with the Asian economy, the main objective of this war, hides three fundamental elements: the decrease in the level of imports that are productive inputs in general; the stagnation of the manufacturing sector (see graph below); and the increase in the trade deficit with Mexico.

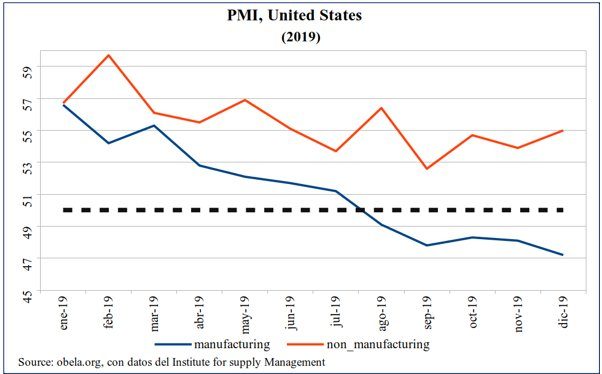

Its protectionism did not improve domestic manufacturing activity either. The Purchasing Manager Index, a monthly indicator built on surveys of entrepreneurs in areas such as production, employment, inventories and new orders, reported a declining trend since the beginning of 2019 but contraction since July 2019, and paradoxically, an expansive trend, although less so, in the service sector. This contraction in the manufacturing sector is due to the slowdown in investment in fixed assets in sectors such as the automobile industry or mining products.

In this context, the US sought: 1) a tariff truce announced on December 13, 2019 and signed on January 15; 2) the unexpected approval (9 to 1) by the Senate of the renewed US-Canada-Mexico free trade agreement (T-MEC) one day later. The trade war against China is one that the US cannot win, and has already cost the fundamental loss of international trade rules and the elimination of the WTO’s appeals tribunal.

Since 2018 the US had been engaged in a campaign to block the election and to reappoint new judges to the WTO’s Appellate Courts. As of December 2018, this court had only one judge, which means that it had no capacity to issue a ruling as at least three judges are required. With this action, the WTO became unable to resolve or regulate international trade and, in practical terms, the international trade order disappeared. Now, the imposition of unilateral tariffs (such as those applied by the United States to steel and aluminium in different countries of the world) can only be seen by American courts.

All in all, these are aspects of the regional and global horizon of 2020. The countries of Latin America can expect the intensification of the struggle between the superpowers to influence the region, observe greater exercises of political destabilization, and suffer tariff and economic blockades to strategic investments. In the world, in the midst of a long recession with economic deflation, without prospects for regional growth and without mechanisms for resolving trade conflicts, the door is open for greater economic, trade and even military conflicts, and also for energy transformations, the essence of the conflict with China.