If a spate of recent headlines in the media is to be believed, the rupee…

What really happened to public spending in 2018-19? C. P. Chandrasekhar and Jayati Ghosh

It is now widely recognised that the Finance Minister misinformed Parliament when presenting the Revised Estimates for central government revenues and expenditures in the Union Budget presented in July 2019. That fact has, however, been largely forgotten, perhaps because to date no Member of Parliament has brought a motion of breach of privilege against her for this act of falsity when presenting the Finance Bill, supposedly the most sacred of bills on which a government can even be defeated.

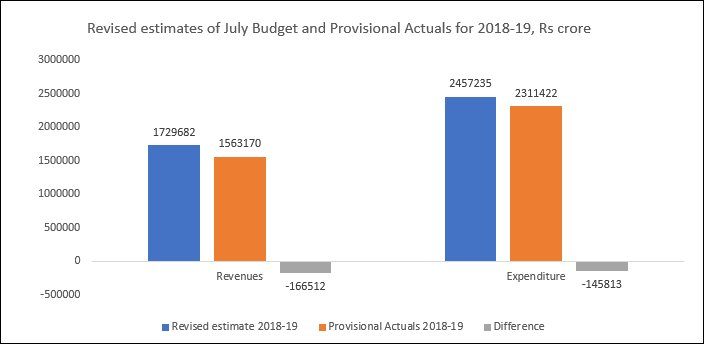

This falsehood was exposed only inadvertently, because the Economic Survey presented by the same Ministry just a day earlier actually contained an Appendix Table that included the “Provisional Actual” figures from the Controller General of Accounts (CGA), which showed very large discrepancy. Effectively, revenues were around 10 per cent lower than the stated figure in the revised estimates, and expenditure was around 7 per cent lower. The differences were substantial in absolute numbers. Despite some public outcry on the matter, the Finance Ministry refused to elaborate or to provide details on these major shortfalls.

As a result, both Parliament and the public were kept in the dark about the actual spending patterns of the central government. This is not just unusual, but against the very spirit of the Constitution (a very battered document in the present dispensation). The reason the Finance Bill is seen as so crucial is because of the underlying assumption that the people of India, through their elected representatives, must be able to judge whether the patterns of revenue mobilisation and financial allocation of the government are appropriate and desirable. Indeed, many hours are spent in debates in Parliament and in public, about the precise allocations to particular Ministries.

But it now turns out that the government of the day has scant regard for what should be serious promises, because it diverges so dramatically from its stated Budget over the course of the year. As Figure 1 shows, there were sharp declines in revenues, and slightly lower declines in expenditure. It is fairly clear what happened. The slowdown in revenue generation was driven by much lower indirect tax collection, as the GST failed to bring in the expected revenues (even though it managed to create havoc in the economy and add to the woes of small and medium enterprises). To counter this, and in order to hold on to the fig leaf of maintaining its fiscal target, the central government slashed its spending.

It is another matter that the true central government expenditure is actually much higher if the dues of the central government (to the employment programme, the Food Corporation of India and several other public sector enterprises) are taken into account, as the CAG has noted. What it does mean, though is that public expenditure was cut to much below target even though there was already evidence that the economy had started slowing down and public spending would be required to revive it.

Figure 1: Both revenues and expenditure of the central government

were well below its claims in the Budget of July 2019

However, because the central government maintained its now familiar secrecy, Parliament and the public were not told how exactly these spending cuts were achieved. Were they proportional cuts across the board? Or did they fall disproportionately on some Ministries and programmes? We can now get answers to those questions based on data from the Controller General of Accounts. That evidence makes it clear why the government chose not to reveal these figures to Parliament, for it is a damning indictment of this government’s spending priorities.

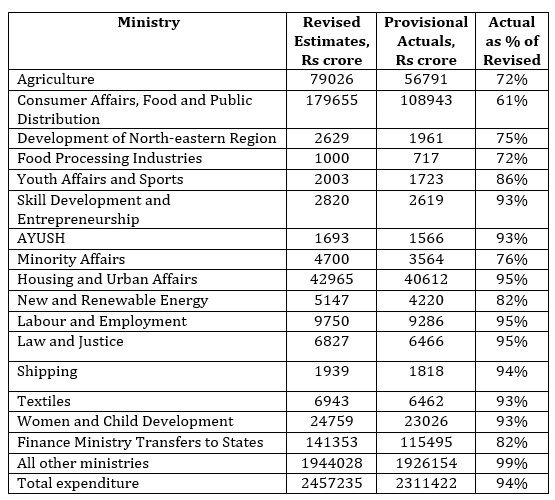

Table 1: Ministries that experience most cuts in spending in 2018-19

It turns out that the spending cuts were truly unbalanced – only a few Ministries experienced severe spending cuts, while the majority faced no cuts at all or only marginal cuts. Table 1 presents the data for the Ministries that faced cuts of 5 per cent or more. They are all dealing with matters of prime social and developmental importance, and therefore the extent to which many of them were cut is truly shocking. In addition, central government transfers to the states were also cut sharply – not just what was their share of GST revenues, but also capital transfers, which were only around half of what was budgeted. By contrast, all other Ministries taken together spent 99 per cent of the allocated amount – in other words, they were largely unaffected.

For example, in a period of acknowledged agrarian crisis, even as farmers’ protests and long marches undertaken at great personal sacrifice by cultivators across the country rocked the nation, the Ministry of Agriculture spent 28 per cent less than the revised estimates claimed, which was already less than the budgeted allocation. Similarly, the Ministry of Consumer Affairs, Food and Public Distribution spent only around half of what was stated in revised estimates. So it may be no surprise that India slipped down so many places in the Global Hunger Index, with this level of attention and concern from the government. Minority affairs is very clearly unloved by this government, as is law and justice, but the proportionate decline in spending for the Northeast and for food processing industries is still surprising.

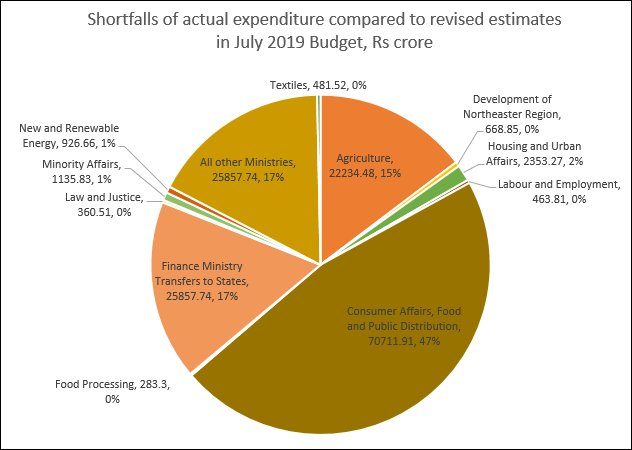

Figure 2

Figure 2 gives some idea of the significance of this distribution of shortfalls. Agriculture and food and public distribution account for nearly two-thirds of the decline in spending, or 62 per cent. The reduced transfers to state governments accounted for 17 per cent, reiterating the cynical starving of state finances that has been a strong feature of this central government.

It is indeed shocking that the government appears to have got away with such unevenly distributed and unjust cuts in its spending, and almost got away with misleading Parliament and the people by purveying fraudulent numbers. These are matters that must be widely discussed in society and especially in Parliament, to find means to redress the injustice involved.

(This article was originally published in the Business Line on December 3, 2019)