Donald Trump’s top economic advisor claims the President has weaponised tariffs to ‘persuade’ other nations…

Warning signs from External Trade C. P. Chandrasekhar and Jayait Ghosh

As if all the bad news from the domestic economy were not enough, foreign trade data suggest worrisome trends on the external front as well. The latest report of monthly trade data from the Ministry of Commerce and Industry indicates that merchandise exports (in US $ terms) in April 2019 increased by only 0.64 per cent over April 2018, while imports grew by 4.48 per cent. This stagnation of exports is truly worrying because it is well below the rate of growth of world exports in the same period.

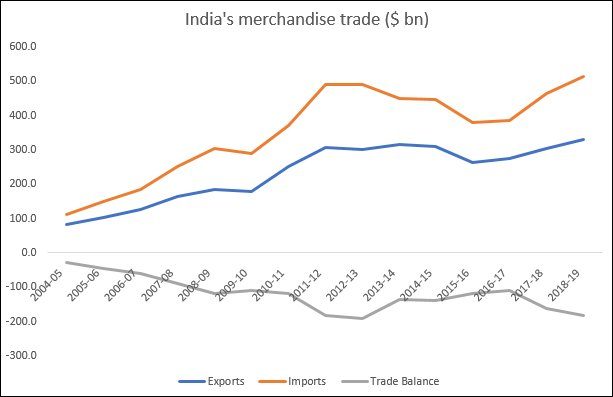

But is this just some current problem, or have external trade concerns been building for a while? Figure 1 considers the movement of the trade balance over the past fifteen years, since the start of the first UPA-1 government. The year 2014-15 showed a seriously large merchandise trade deficit for India, at $138 billion. This declined in the subsequent two years, but then started rising again so that in 2018-19 it reached as much as $184 billion – or a whopping 6.7 per cent of the estimated GDP!

Figure 1: Trade deficits have been building for the past two years

In normal times, this would have been ringing alarm bells for any government, and when combined with the bad news within the economy such as falling investment, clear evidence of sagging demand, falling employment and historically high open unemployment rates, it should have been seen as another indicator of economic emergency. But the government has been adept at deflecting attention from this, to the country’s detriment.

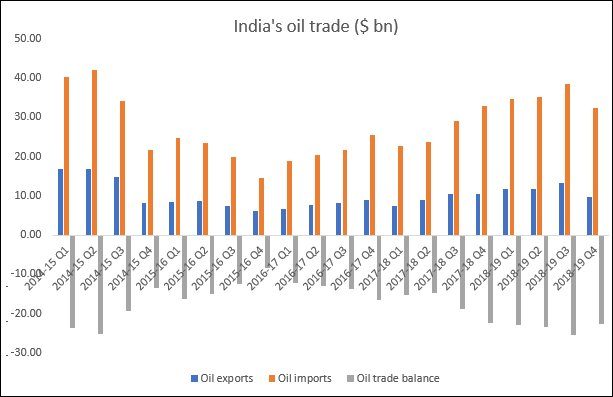

Consider then how the trade indicators have performed just under the tenure of the Modi government. It is often argued that India’s external trade balance is hugely driven by the world oil price, since India remains a significant net importer of oil and petroleum products. Figure 2 shows that for the first half of its tenure at least, the Modi government was a major beneficiary of the decline in global oil prices. By mid 2016-17, these had caused the oil import bill to fall to less than half of its level in the first quarter of 2014-15, when the government assumed office. Thereafter, as oil prices have risen, so has the oil import bill. But this increase was not as much as could be expected, because domestic demand has not been rising as much as would be warranted by the supposedly high GDP growth.

Figure 2: Rising global oil prices have worsened the oil trade deficit

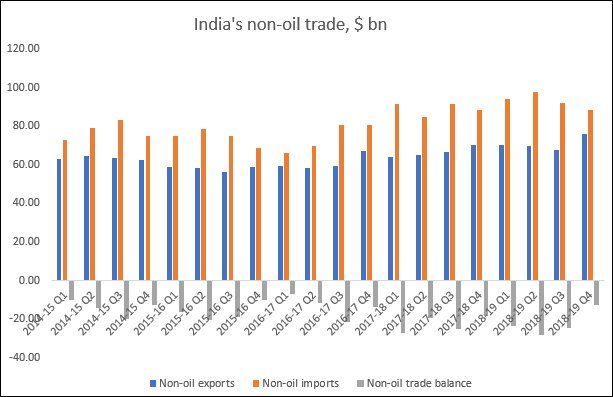

What may be more alarming is the continued increase in the non-oil deficit. As Figure 3 indicates, non-oil exports have been growing sluggishly if at all, except for an apparent spurt in the most recent quarter. However, non-oil imports have continued to increase suggesting greater substitution of domestic production in a situation of already stagnant demand. This bodes ill for domestic producers, especially small producers that are more threatened by cheaper import competition, and therefore it is no surprise to learn of survey data pointing to significant declines in manufacturing output.

Indeed, the latest monthly trade data suggest that the sectors showing the most rapid increase in imports in April 2019 are precisely those manufacturing sectors that also include many small and medium sized enterprises: pulp and waste paper; textile yarn and fabrics and made-up articles like garments; leather and leather products; dyeing, tanning and colouring materials; machine tools; electronic and professional goods; chemicals and pharmaceuticals. In such a context, we can hardly be surprised that employment in such manufacturing activities has been declining.

Figure 3: Non-oil trade deficits have been large and mostly increasing

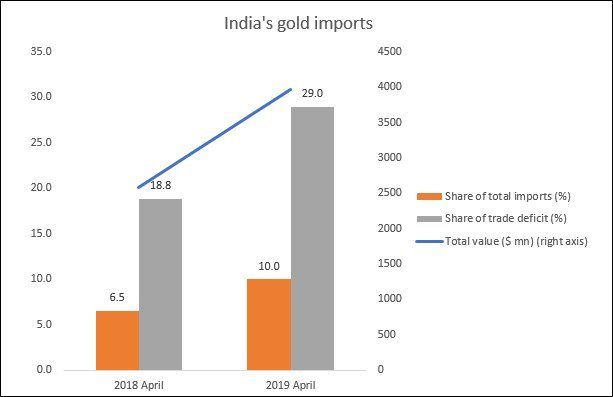

Figure 4: The bane of growing gold imports

But one of the biggest reasons for the rising trade deficit is also one of the least desirable: the significant increase in gold imports. Figure 4 shows how these have exploded in the past year, with the value in April 2019 as much as 60 per cent higher than in the previous year. In fact, non-oil non-gold imports actually declined by 2.2 per cent in April 2019 (year-on-year) which shows how significant the role of gold imports has been in causing this ballooning trade deficit. By April 2019, gold imports alone accounted for nearly 30 per cent of the trade deficit.

India has always been “a sink for precious metals” as Keynes described it nearly a century ago, but gold imports tend to rise particularly in periods of domestic economic uncertainty. But these completely unnecessary imports can also be controlled through appropriate policy action, which has unfortunately simply not happened recently. This is one more economic problem that could be quite simply and effectively dealt with by a proactive government, yet nothing is being done about it.

It is surprising – and speaks volumes for the subservience of India media – that, while the last few years of the UPA-2 government were condemned for their “economic policy paralysis”, there has thus far been very little negative commentary on the economic mismanagement of the Modi regime. Problems created within the country by incompetent economic policies are being multiplied by headwinds from the global economy. As a result, whichever government is formed after 23 May will face many major challenges in dealing with the economy, including in sorting out the mess in the foreign trade account.

(This article was originally published in the Business Line on May 21, 2019)