“This is a new form that inter-imperialist relations have taken. It is not the old…

The Aging of a Growth Engine C.P. Chandrasekhar and Jayati Ghosh

For India’s post-liberalisation poster-child, the software and IT-enabled services industry, recent developments in the global economy are bound to be disconcerting. Even as early signs of a synchronized global recovery emerge, fears of inflation and high interest rates have resulted in a collapse of capital markets. What that could do to the incipient recovery is as yet unclear and the prognosis is uncertain. But for an industry that has been battling a slowdown ever since the 2008 global financial crisis that is clearly not good news.

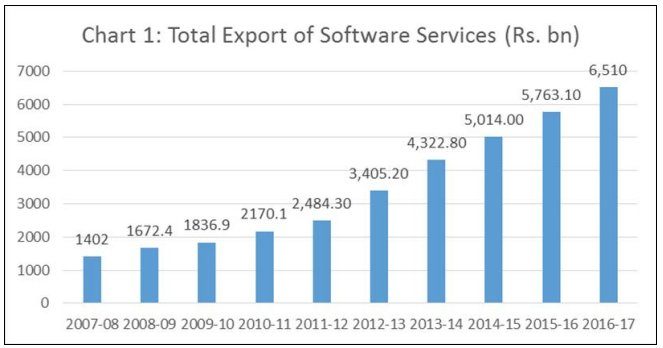

According to RBI survey figures released in December last year, India’s approximately $150 billion information technology industry, earned $97.1 billion in foreign exchange in 2016-17, as compared with $88 billion in 2015-16, through the exports of software and IT-enabled services. That 10 per cent rate of growth does not seem too bad, just as the near continuous increase in the rupee value of export of software and IT-enabled services (Chart 1). The true story resides, however, in the figures on growth of these exports in dollar terms in the years after the global crisis.

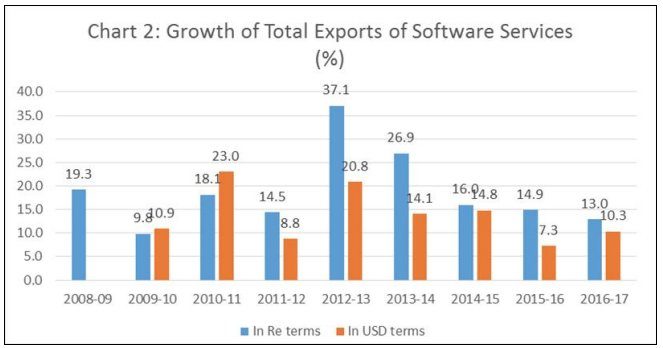

According to data from the Reserve Bank of India the rate of growth of the combined exports of software and IT-enabled services in dollar terms has fallen from 20.8 per cent in 2012-13 to 14-15 per cent during 2012-15, and further to 7.3 and 10.3 per cent in 2015-16 and 2016-17 (Chart 2). Fluctuations of the rupee result in significant divergences between growth rates of exports denominated in rupee and dollar terms, with the former exaggerating growth in most years. It is the dollar value of exports that capture actual export performance.

Besides revealing the downward trend in the dollar value of software and IT-enabled exports, these figures are disconcerting because they point to the aging of an industry that was for long accustomed to much higher rates of growth of exports and revenues, and, along with remittances from Indian workers abroad, had helped shore-up India’s balance of payments. In the first 15 years after the launch of liberalization, India’s IT industry recorded remarkable growth because it exploited an outsourcing opportunity by perfecting a global delivery model for software and IT-enabled services based on cheap skilled labour.

As a result, IT industry revenues grew at high double digit levels with export earnings accounting for a large share of those revenues. However, there were a number of features of that model that made it vulnerable to the changed circumstances since the global crisis of 2008. To start with, the industry’s exports were largely directed to the US market, followed by the EU at a distant second. If at the turn of the century the North American market accounted for close to two-thirds of India’s IT exports and the EU for about a quarter, even in 2016-17 the US and Canada came in first with 60 per cent of the industry’s exports and Europe second with 23 per cent. Not much has changed.

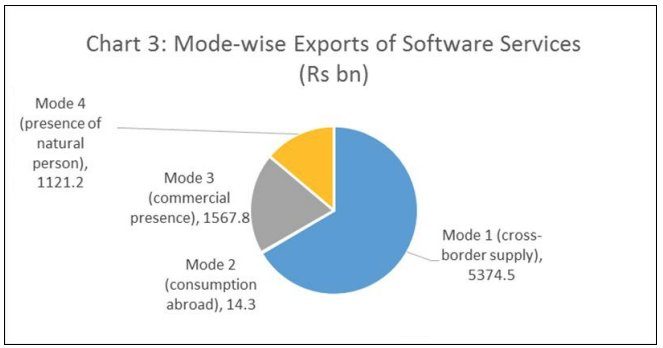

Secondly, the delivery model required combining offshore delivery with local services provision, to customize services and even maintain operations. So onsite work remained an important component of the industry’s activity. In 2002-03, 48 per cent of India’s exports of IT services was through the medium of a commercial presence in foreign soil and another 13.5 per cent through the presence of natural persons. By 2016-17 those figures had come down to 19.9 and 13.9 per cent respectively. Thus, more than a third of revenues depend on operations abroad (Chart 3).

Given these characteristics, a range of developments since the global crisis of 2007-08 have been posing challenges to the industry. Since the financial crisis and the Great Recession that followed originated in the US and affected mainly the developed countries, the main markets of the industry have turned sluggish. On average demand growth has been low by historical standards. Overall, precisely at a time when the industry had grown to maturity and was hard put to maintain market share and grow at dramatic rates, the markets themselves were losing momentum.

Moreover, the absence of any robust recovery a decade after the crisis first broke has set off protectionist tendencies. The accusation that on-site provision of services by firms from India based on H1-B visas involves the importation of cheap labour for tasks that can be easily performed by available and unemployed local labour has grown louder. To deal with this perceived “misuse” of H1-B visas, the Trump administration under its “Hire American” programme has chosen to set a high floor to the annual salary that must be paid to those availing them. In November 2017, the House Judiciary Committee, in a first step to enact a new law, passed a bill to raise the minimum salary raise for H-1B holders from $60,000 to $90,000, besides subjecting H-1B dependent employers (or those employing H-1B workers to the extent of 20 per cent of their workforce) to greater scrutiny. The Protect and Grow American Jobs Act seeks to make it more difficult for “H-1B dependent” companies to access new permits to hire foreign workers.

Trump has also issued an executive order that aims to prevent “fraud “in the use of such visas, by making sure that they are used only to import workers with advanced degrees and higher skills. Here too salary paid is to be used as an indicator of worker quality. That can be damaging. According to the Financial Times, “(m)ore than 80 per cent of the workers now on H-1B visas earn less than the US median wage for their jobs,” and “(j)ust 5 per cent have earnings in the highest wage tier.” Indian workers account for 70 per cent of H1-B visas issued, according to data from the US Department of State. Accommodating more of them could turn difficult. And they would have to be paid much higher wages, raising costs and squeezing profits.

Simply put, the global financial crisis has changed the external circumstances confronting the software and IT-enabled export sector. The problems associated with generating a recovery is only making matters worse. Aging has combined with these circumstances to make the industry less dynamic, with firms that had made their name early and established their presence continuing to dominate a sector afflicted by decelerating growth. If the industry has to remain a leading sector it clearly needs to rediscover itself.

(This article was originally published in the Business Line on February 13, 2018.)