Corporate-dominated food systems are responsible for widespread but still spreading malnutrition and ill health. Poor…

Opacity in India’s Budget Numbers will have Major Implications for Investors Jayati Ghosh

Budget 2020, presented by India’s finance minister Nirmala Sitharaman on Feb. 1, turned out to be worse than a damp squib. It was such a disappointment that its impact on an already weak economy now facing global headwinds, may verge on the disastrous.

To paraphrase an expression recently popularised on the streets of many Indian cities: it’s so bad, even the stock markets and industry representatives are protesting!

Let’s leave aside the minor irritants, such as the fact that the longest, and possibly most tediously presented, budget speech in Indian history was woefully short on vision, economic strategy and necessary fiscal details. Let’s focus instead on what makes this budget especially problematic for the economy, immediately and in the future.

The economic backdrop

Consider the context in which this budget was presented.

India is in the midst of an economic crisis. A slowdown of economic activity, collapse in employment generation, suppression of consumer demand, hesitation of private investment and the bad loans problem of both banks and non-bank lenders have combined with declining exports to create a major problem of inadequate demand.

In this depressed macroeconomic situation, only the government can pull the economy out of its quagmire. That’s why the voices asking, even begging, for a significant fiscal stimulus have recently multiplied, encompassing private investors and economists across the ideological spectrum.

It was, therefore, widely expected that the government would, at least temporarily, put aside its obsession with pretending to adhere to fiscal “discipline” and increase public spending.

Ideally, this would encompass increased expenditure in sectors with high multiplier effects like the rural employment guarantee programme, agriculture, health, and education, besides infrastructure.

Even the Economic Survey put out by the finance ministry noted (in Volume II, rather than the more embarrassing Volume I) that “considering the urgent priority of the government to revive growth in the economy, the fiscal deficit target may have to be relaxed for the current year.”

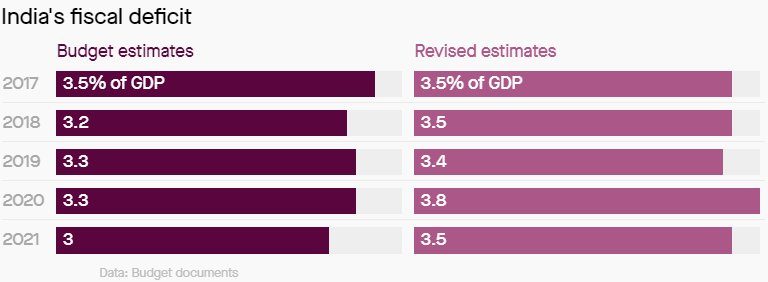

The budget, though, failed miserably to come up to scratch on this crucial matter. True, the proposed fiscal deficits for this year and the coming year are pegged at 3.8% and 3.5% of GDP respectively, but these are meaningless numbers, as I will explain later.

Curtailed spending

The spending plans of the government are what matters, and here the outlays are woefully inadequate to the task at hand.

Critical areas like agriculture, the employment programme, food security, health, and sanitation continue to be starved of funds, and in some cases cut down even further, which means that there will be no revival in consumer demand. Public investment plans are paltry. The longer Sitharaman spent talking about certain items, the less money she appears to have allocated to them.

State governments are getting smaller shares of their tax revenues and even being denied their rightful compensation for the goods and services tax (GST), meaning they cannot increase spending either.

Meanwhile, the budget proposes further income tax cuts that are likely to benefit only foreign portfolio investors and the uber rich, which will do little to improve aggregate demand or real investment, while adding to the inequalities in the economy.

Dubious numbers

What may be even more problematic is that we can no longer trust the budget numbers, either for the current year or the forthcoming one.

The government has brought in a whole new level of opacity in the budget numbers, to the point that the revised estimates presented for revenues and spending in financial year 2020 are not just slightly off but completely unbelievable.

We have data on central government receipts and expenditure up to December-end 2019, that is the first nine months of this fiscal year, from the controller general of accounts. From that source, we know that total receipts of the central government in the period were only 44% of the claim of the revised estimates for the entire year. In other words, the finance minister expects around two-thirds of the expected revenues to come in the last three months!

Similarly, 60% of tax revenues will also accrue in the last quarter, if the revised estimates are to be believed.

We know this will not happen, and so does the finance ministry. So it is probably already doing exactly what it did last year—putting a further squeeze on many ministries to cut back their spending in the last quarter of this year.

In addition, it will also probably continue to avoid paying its dues to state governments, to public sector undertakings, to the Food Corporation of India, to Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Employment Guarantee Act (MNREGA)—the rural employment guarantee programme, which, by law, is supposed to be a demand-led programme with no budgetary constraints—and so on.

This may create financial and debt problems for all these unpaid agencies, but so far at least, the central government doesn’t seem to care.

Last year, the biggest cuts came in the most essential areas like food, agriculture, rural development, housing, health, and education, as well as in transfers to state governments. It is likely that something similar will happen this year as well, especially as these ministries have already underspent significantly compared to the budget estimates.

These are all employment-intensive areas, that are also crucial for future growth potential, so cutbacks in these have serious consequences.

Recessionary tendencies

Apart from the serious loss of credibility of the budget numbers, which has massive implications not just for economic commentary but for investors, there is a major macroeconomic concern.

The central government is actively adding to the recessionary tendencies in the Indian economy, at a time when this is the very opposite of what is required. The economy operates according to its own rules and cannot be made to “behave,” unlike people who can be manipulated, shouted down or intimidated into silence or acceptance. That is why the Modi government clearly has particular difficulties with its economic strategy.

Unfortunately, the main losers in this process are not the government but the Indian people, who now face an economic crisis of potentially massive proportions.

(This article was originally published in Quartz India: February 3, 2020)